On Friday, for the next several weeks, I’ll be posting a series of articles examining how the world is becoming more urbanized and how governments, businesses, and citizens must adapt to ensure that urban growth is done intelligently. I’ll discuss how big data can help influence city planning and operations as well as help manufacturers and retailers ensure that their products and services are available to urbanites. These topics are generally grouped together under the topic of smart cities. I believe that resilient cities are smart cities. Dr. Boyd Cohen, a climate strategist, believes “the smart-cities movement is being held back by a lack of clarity and consensus around what a smart city is and what the components of a smart city actually are.” [“What Exactly Is A Smart City?, Fast Company, 21 September 2012] He continues:

“While some people continue to take a narrow view of smart cities by seeing them as places that make better use of information and communication technology (ICT), the cities I work with … all view smart cities as a broad, integrated approach to improving the efficiency of city operations, the quality of life for its citizens, and growing the local economy.”

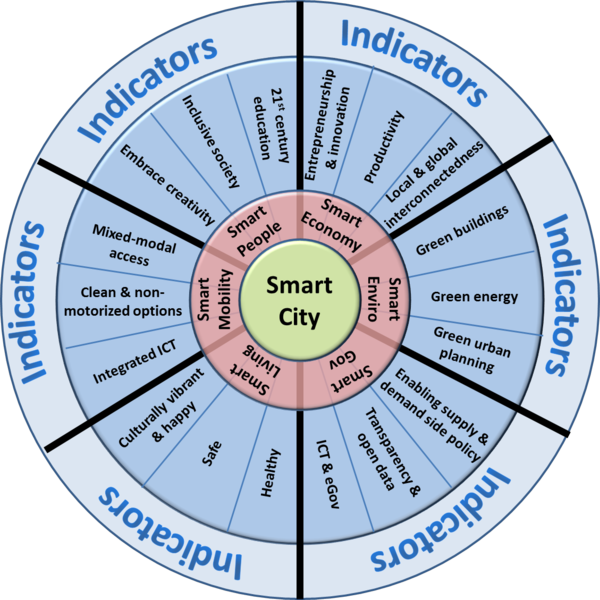

Although I’m a technology guy, I agree with Cohen that a broad definition of what constitutes a smart city is better than a narrow one. To show how various city sectors come together to make a smart city, Cohen has developed what he calls the Smart City Wheel. At the hub of the wheel, you find smart people, smart government, smart economy, smart environment, smart mobility, and smart living.

Cohen admits that his “model has been inspired by the work of many others.” The fact that many others are working to make cities smarter should be encouraging, especially in the light of the fact that urbanization is occurring at an historical rate. Cohen indicates that “there are over 100 indicators to help cities track their performance with specific actions developed for specific needs” behind the model. He says that efforts to create a smart city should begin with three steps. They are: 1) Create a vision with citizen engagement; 2) Develop baselines, sets targets, and choose indicators; and, 3) Go lean.

Rick Robinson, an Executive Architect at IBM specializing in emerging technologies and Smarter Cities and a self-labeled Urban Technologist, has his own ideas about to get a smart cities program started. [“How Smarter Cities Get Started,” The Urban Technologist, 26 July 2012] He writes:

“Many of the environmental, social and economic forces behind the transition to Smarter Cities are common everywhere; however, the capabilities that enable cities to act in response to them are usually very specific to individual cities. They depend on factors such as geographic location, the structure and performance of the local economy, the character of local communities, and the approach of leaders and stakeholders across the city. The relationships between those stakeholders and communities are crucial. Cities may aspire to encourage economic growth amongst small, high-technology businesses; or to stimulate innovation in service delivery by social enterprises; or to switch to more sustainable patterns of travel and energy usage. To act successfully to achieve any of these aims, long and complex chains of connections between individuals need to work effectively, from city leaders, through their organizations, to community and business associations such as small business forums, neighborhood communities, and faith groups, to individual companies, their employees and citizens across the city.”

Robinson makes an important point about the uniqueness of each urban area’s situation. The only way to discover that uniqueness, and the connections that are critical for improving society, is through analysis of big data. As Robinson notes in his article, a “complex web of city systems” must be woven into a cohesiveness system working together towards the same objectives. He doesn’t claim to have all of the answers about how this can be done, but he writes that there are observable “patterns in the behavior of the cities who have made the most progress.” He states it all starts with a plan.

“Cities already have plans, of course. In fact, often they have lots of plans – for the economy, for housing, for public service transformation, for marketing and for many other aspects of urban systems. What is really required in a Smarter City context, though, is a single plan that captures the vision and means for transformation; and that is collectively defined and owned by stakeholders across the city; not by any single organization acting alone. It needs to be consistent with existing plans within individual domains of the city; and in time needs to influence those plans to develop and change.”

While working in the risk management area several years ago, we noticed that, because large organizations have departmental silos, each department usually maintains its own mitigation and recovery plan. Because those plans aren’t coordinated, actions necessary to make one plan work (like shutting down a system) could negatively impact the mitigation plans of other departments. Only through effective coordination could the overall objective of protecting the organization be realized. The same thing holds true when developing a plan for a smart city; plans must be coordinated (if not integrated) so that various groups aren’t working at cross purposes. Technology, like the Sense, Think, Act, and Learn® system being developed at Enterra Solutions®, can be used to code natural language plans and then analyze them to discover conflicts, redundancies, non-obvious connections (inferences) and so forth. The same technology can be used to discover the unique qualities of neighborhoods and the important connections between stakeholders that are often not easy, or obvious, to understand. Robinson continues:

“A Smarter City plan needs to set out a vision that is clear and succinct, often expressed in a single sentence capturing the future that the city aspires to. That vision is usually supported by a handful of statements that summarise its impact on key aspects of the city – such as wealth creation, inclusivity and sustainability. Together these statements are something that everyone involved in the city can understand, agree to and promote. … To make the vision deliverable, a set of quantified objectives against which progress can be measured are vital. In IBM as we work with cities to establish these measures, we’re learning that social, financial, environmental, strategic and brand values are all important and related. They could include improvements in education attainment; creation of jobs; increase in the GDP contribution by small businesses in specific sectors; reduction in carbon impact in specific systems or across the city as a whole; improvements in measures of health and well-being; and may include some qualitative as well as quantifiable criteria. It is against such objectives that specific programmes and initiatives can be designed in order to make real progress towards the city’s vision.

In other words, Robinson agrees with Cohen that creating a vision is a critical first step towards a smarter city. Robinson believes that the vision is also critical for aligning stakeholder actions for achieving success. To ensure that stakeholders stay engaged and motivated, Robinson recommends “a mixture of long and short-term projects across city domains; and in particular that [the plan] includes some ‘quick wins’ – in attempting to work in new partnerships to achieve new objectives, nothing builds confidence and trust like early success.” Like Cohen, Robinson believes that everyone must be engaged for a plan to succeed. He writes:

“Once stakeholders from a city ecosystem have come together to define a vision and a plan to achieve it, it’s vital that they maintain a regular and empowered decision-making forum to drive progress. The delivery of a Smarter City plan relies on many separate investments and activities being undertaken by many independent individuals and organisations, justified on an ongoing basis against their various short-term financial obligations. Keeping such a complex programme on track to achieve cohesive city-level outcomes is an enormous challenge. Such forums are often chaired by the city’s local authority; and they often involve representatives from local universities who act as trusted advisors on topics such as urban systems, sustainability and technology. They can include representatives from local employers, faith and community groups, institutions such as sports and retail centres, and trusted partners in domains such as technology, transport, city planning, architecture and energy. The broader the forum, the more completely the city is represented; but these are ‘coalitions of the willing’, and each city begins with its own unique mix. In fact, a formative event or workshop that brings such city stakeholders together for the first time, is often the catalyst for the development of a Smarter City plan in the first place.”

Like many projects, initial excitement for smart city initiatives can be high and then taper off over time. Keeping people engaged is absolutely essential. That won’t happen if the smart cities movement is viewed as a passing trend. Ben Rooney writes, “In the pantheon of Next Big Thing trends, the concept of ‘smart cities’ is one of the trendiest.” [“‘Smart City’ Planning Needs the Right Balance,” Wall Street Journal, 27 September 2012] Rooney’s fear is that smart cities initiatives will be driven by well-meaning, but clueless, governments and that “there is a fear that such top-down programs may threaten the very vitality that attracts people to cities in the first place.” Done correctly, smart cities should increase the vitality of cities not diminish it. That’s why Cohen and Robinson are so insistent that all stakeholders need to be engaged.

Rooney agrees that smart cities initiatives are generally based on data analysis. He claims, however, that doing so is nothing new. He explains:

“One of the first uses of data to drive civic policy was more than 150 years ago when during the 1854 London cholera outbreak surgeon John Snow plotted cases on a map. He traced the outbreak to a water pump in Broad—now Broadwick—Street. When the pump handle was taken off, the number of cases immediately began to decline.”

Imagine that kind of analysis being applied to urban challenges based on enormous amounts of data and using today’s massive computer power. Health and safety are very important areas where connectivity and analysis can play a vital role. This value was recently demonstrated during the investigation that followed the terrorist bombings in Boston. Video and photographic evidence were critical in catching the perpetrators. Enterra Solutions has helped install a system at the Port of Philadelphia that has been recognized for helping make the port more secure. Holt Logistics’ Chief of Security, Kurt Ferry, praises the system as “an example of a successful collaboration between private and public sector organizations using grant funds to enhance regional maritime security.” [“Security Grants Help Improve Domain Awareness: A Success Story,” The Beacon, Winter 2011] According to Rooney, cities of the future (like one being built in Portugal) will be even more connected. He writes:

“PlanIT is a €10 billion, four-year project to build a new smart city in Portugal to house some 225,000 people. With sensors built into every building it presents itself as an urban utopia where smart buildings can sense our presence and anticipate our needs. But behind this drive for efficiency is a fear that optimizing for data will drive out the inefficiencies that imbue cities with their humanity; cinematic history is littered with cautionary urban dystopias, from Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’ to the Wachowski brothers’ ‘The Matrix.’ As Ben Hammersley, the U.K. prime minister’s ambassador to Tech City, told the audience at the recent WSJ Tech Cafe event, optimizing is a dangerous thing unless you are quite clear on what exactly you are optimizing.”

You recall that one of Cohen’s first steps was to “go lean.” Rooney is warning that you can go too lean. I agree. Hammersley an adviser to the Danish city of Aarhus, gave the Tech Cafe audience a specific example of what he was talking about. He told him:

“‘Most smart-city initiatives are about optimizing the route for commuters getting to the office,’ he told the audience. ‘But Aarhus, which has the highest number of pavement cafés in the country—it is essentially one huge café—doesn’t want to optimize that. The lesson is be careful what you measure because you may end up optimizing on the wrong thing.'”

That’s where big data analysis and relationship discovery technology can play a major role in helping cities become the best they can be. Rooney labels the use of big data as “a bottom-up” approach to smart city planning. He writes:

“A very different kind of smart-city initiative has had success in cities as diverse culturally and geographically as San Francisco and Singapore, and is coming to Europe. Called Urban Prototyping, the movement approaches cities from a bottom-up—not top-down—viewpoint. Peter Hirshberg, who lives in San Francisco, is the man behind the drive, which aims to bring together programmers, planners, activists, and even artists to use data and technology to solve problems in cities. ‘There needed to be a dialog between people doing interesting things and the folks running the city,’ he said. ‘San Francisco is awash with data, but it turned out that inside the bus system the guys use Walkie Talkies and clipboards to track busses that break down.’ Over one weekend in July 2011 … developers built an iPad app to solve this problem. ‘Everyone wants the busses to run properly. This was a case of citizens getting together and solving a problem.’ He cites dozens of other examples. ‘We had a festival called “The Summer of Smart”. The head of public works for San Francisco came along with a proposal. “Where I see public art I don’t see graffiti,” he told us. “Where I see graffiti, I don’t see public art.”‘ The result was a project called Art Here that brings together the two.”

Although it sounds great, Rooney admits that even the best-intentioned efforts need champions who can make things happen. He reports that nine months after the bus app had been developed for the city, it still hadn’t been implemented. That kind of underwhelming response can trigger both anger and ambivalence. As Rooney put it, “City Hall has proved to be the movement’s biggest challenge.” He concludes, “If this movement is to make a real impact on the lives of city dwellers it will take more than some well-intentioned hackers and a lot of pizza.”

I’m speculating that is why one of the main sectors on Cohen’s Smart Cities Wheel is Smart People. Based on advertisements run during the last political season, it’s clear that we could use a lot more smart people in government. Robinson agrees that “it’s impossible to understate the importance of individual people in making cities Smarter. The functioning of a city is the combined effect of the behavior of all of the people within it; and Smarter City systems will not change anything unless they engage with and meet the needs of those individuals.” Fortunately, I’m an optimist. I believe that technology can be used to create a better future and smarter cities.