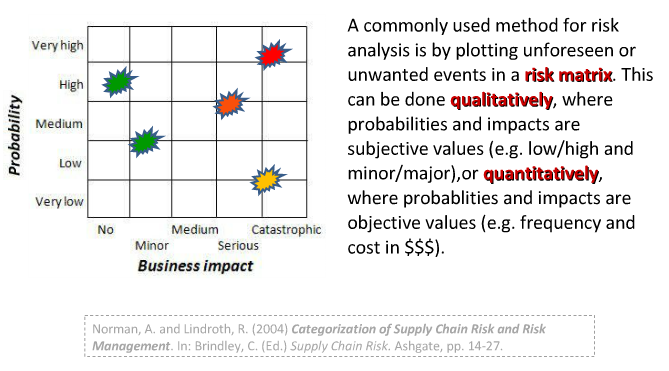

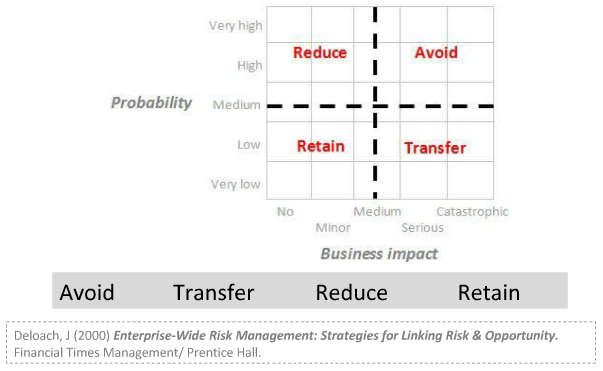

Supply chain risk management is a very complex subject. It has been (and will continue to be) the subject of numerous studies and books. The focus of these studies has ranged from basic definitions to very complex mathematical explanations about how to improve risk management. Risk itself is a very ambiguous concept. Normally, risk is defined in terms of potential and consequences. Some studies have depicted a risk formula this way: Risk = Probability x Consequences. That formula results in simple 2 x 2 framework for assessing and managing risk, where on one dimension is the likelihood of occurrence (high or low) and the other the level of impact (high or low). Occasionally, this 2 x 2 matrix is fancied up a bit (such as the one shown below that was used in a slide show on risk management by Jan Husdal); but, the underlying concept remains the same.

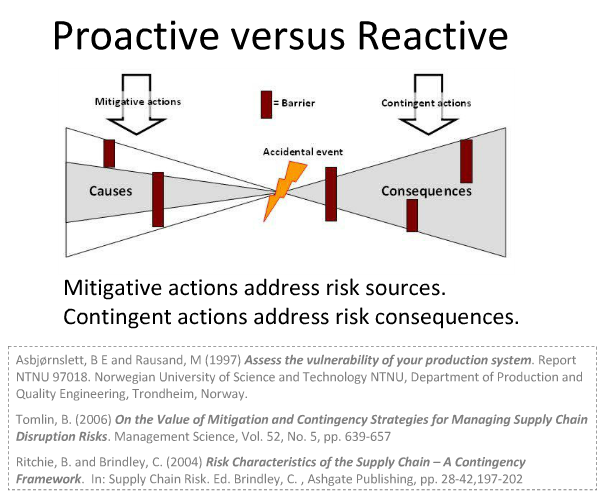

Few scholars and analysts today believe that this simple framework is sufficient to obtain a full understanding of risk management. Some analysts argue, with good reason, that the time element needs to be accounted for when assessing risk. For more on that aspect of risk management, read my post entitled Assessing the Time Element of Supply Chain Risk Management. Another slide presented by Husdal demonstrates that one part of the time element that needs to be considered is when to act. You’ve heard the old saying, “Timing is everything.” The following graphic highlights the fact that both mitigative and contingent actions may be (and probably are) required.

Back in 2004, Dr. Andreas Norrman and Robert Lindroth wrote, “The terms ‘risk’ and ‘uncertainty’, as well as ‘Supply Chain Management’ (SCM), are very ‘broad’ in their definitions.” [“Categorization of Supply Chain Risk and Risk Management,” Chapter 2 in Supply Chain Risk, edited by Clare Brindley, Ashgate Publishing] Norrman and Lindroth define supply chain risk management this way:

“Supply chain risk management is to collaboratively with partners in a supply chain apply risk management process tools to deal with risks and uncertainties caused by, or impacting on, logistics related activities or resources.”

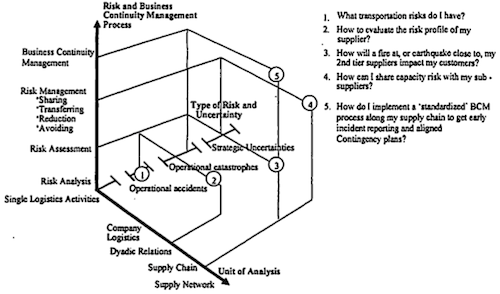

The purpose of their chapter, however, was not to argue definitions but to present “a framework that can be used to categorize issues within supply chain risk management: both research areas and managerial issues.” Commenting on their work, Daniel Dumke writes, “Norrman and Lindroth suggest a three dimensional framework to analyze different supply chain risk management issues (figure 1).” [“Categorization of Supply Chain Risk and Risk Management,” Supply Chain Risk Management, 16 May 2011] The dimensions are:

- Unit of analysis, describing the levels which are affected by this issue (more local to the company or affecting the whole supply network)

- Type of risk or uncertainty, describing if the issue is operational or strategic

- Risk and business continuity management process, which shows the stage within the risk management process

Figure 1: Supply Chain Risk Management Framework (Norrman and Lindroth, 2004)

You’ll notice that Norrman and Lindroth didn’t have a time dimension associated with their framework. Yet it’s clear that whenever you address things like business continuity that time is a critical factor. Nevertheless, the framework is useful because it adds depth to the traditional 2 x 2 matrix. Dumke continues:

“The framework can be applied to many supply chain problems, an example of which can be found in figure 2.

Figure 2: Application of Supply Chain Risk Management Framework (Norrman and Lindroth, 2004)

Dumke likes the Norrman and Lindroth approach since their definition of supply chain risk management deals “with more than the risk from a single company.” He appreciates this “broader perspective” as well as the fact that their framework “also considers the rippling effects of events connected entities.” Dumke continues:

“An important dimension of risk is its contextual association, which can be strategic, financial, operational, commercial or technical:

- Strategic: the risk of plans failing or succeeding, e.g. marketing strategy, changes in consumer behavior or political/regulatory changes.

- Financial: the risk of financial control failing or succeeding.

- Operational: the risk of human error or achievement, e.g. design mistakes, unsafe behavior, employee practices risk, sabotage.

- Commercial: the risk of relationships failing or succeeding, e.g. business interruption due to loss of key executive, supplier failure or lack of legal compliance.

- Technical: the risk of physical assets failing/being damaged or enhanced, e.g. equipment breakdown, infrastructure failure, fires, explosion, pollution, etc.

“But the locational source of the risk is as important and can be divided into (a) externally-driven or environmental risk, (b) internally-driven or process risk, (c) decision-driven or information risk.”

Because there are so many dimensions to supply chain risk management, there are also a number of strategies that are required to deal with those risks. No single strategy can address all types of risks. In his slide show, Husdal depicted several general strategies for dealing with risks depicted in the traditional 2 x 2 matrix.

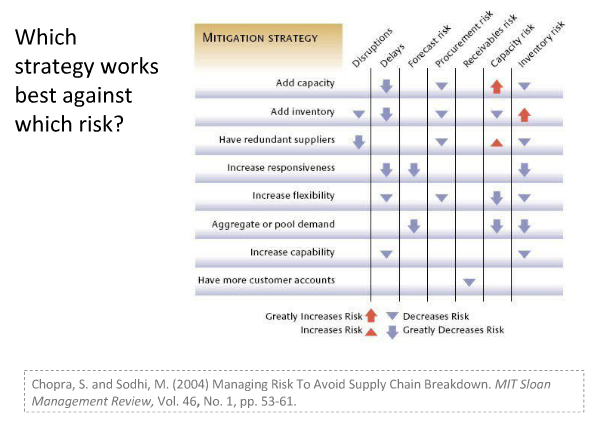

Later in his presentation, Husdal presents other strategic possibilities (as depicted in the following graphic).

Returning to Norrman’s and Lindroth’s work, Dumke reports:

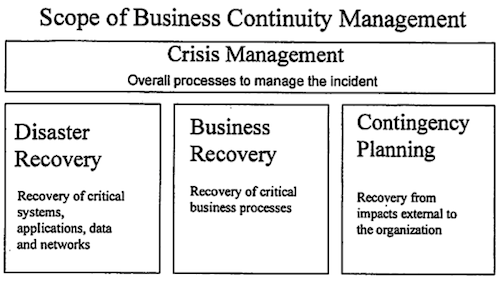

“After highlighting some basic aspects of SCRM and risks in the supply chain context, the authors present their risk management process, which contains three elements: Risk Analysis and Assessment, Risk Management, and Business Continuity Management (BCM). The process starts with a listing of the risks affecting the supply chain using Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) and assessing the effects of those events in case they happen on the supply chain using Event Tree Analysis (ETA). As the second step, the decision has to be made if the risk can be accepted or if the risks can be mitigated by reducing the likelihood or impact. Thirdly, one can argue if BCM (see figure 3) has to be part of a risk management process, nonetheless it is related, since it covers the aspect of planning for when an adverse event happens.”

Figure 2: Application of Supply Chain Risk Management Framework (Norrman and Lindroth, 2004)

Dumke concludes, “The framework combines several important aspects of risk management in general and specifically supply chain management. It is therefore very suitable for an introductory purpose on supply chain risk management.” In the final slide of his presentation, Husdal lists four bullets that sum up the basics. They are:

- Supply chains are exposed to a variety of risks that are unique to each supply chain.

- These risks are related to actions and events that are inside and outside of the supply chain.

- Supply Chain Risk Analysis seeks to identify these risks, their sources and drivers, and their impact on the supply chain.

- Supply Chain Risk Management seeks to establish mitigative and contingent strategies for how to deal with the identified risks and their potential impact on the supply chain.

I have only one quarrel with that summary. It implies that all risks can be identified. They can’t. A good supply chain risk management process does not prepare a company for every possible risk, but it does permit the company to respond quicker and more flexibly to any contingency. Supply chain risk management does not involve a plan that is drawn up and placed on a shelf only to be pulled down and dusted off when a crisis arrives. Good SCRM processes continuously monitor the environment, analyze “what if” scenarios, look for vulnerabilities or weaknesses, and are revised as circumstances change.