According to a survey taken last year, “over 70 per cent of organizations … experienced at least one supply chain disruption in 2010” [“70pc of supply chains hit by disruption,” Supply Chain Standard, 28 October 2010]. The survey, Supply Chain Resilience 2010, was sponsored by Zurich and conducted by the Business Continuity Institute. It covered covers 35 countries and 15 industry sectors. The article about the study continued:

“A key conclusion is that outsourcing, in particular in IT and manufacturing, often ultimately reduces cost-benefits through greater exposure to supply chain disruption. Other findings include:

“* Adverse weather was the main cause of disruption around the world, with 53 per cent citing it – up from 29 per cent last year.

“* Unplanned IT and telecommunication outages was the second most likely disruption and the failure of service provision by outsourcers was third, up to 35 per cent from 20 per cent in 2009. These incidents led to a loss of productivity for over half of businesses.

“* The average number of identified supply chain risks in the past 12 months was five, with some organization reporting over 52.

“* 20 per cent admitted they had suffered damage to their brand or reputation as a result of supply chain disruptions. For ten per cent of companies the financial cost of supply chain disruptions was at least 500,000 euros.

“* Where businesses have shifted production to low cost countries they are significantly more likely to experience supply chain disruptions, with 83 per cent experiencing disruption. The main causes were transport networks and supplier insolvency.

“* 50 per cent have tried to optimize their businesses through outsourcing, consolidating suppliers, adopting just-in-time, or lean manufacturing techniques.

“* Only 7 per cent had been fully successful in ensuring suppliers adopted business continuity management practices to meet their needs, with nearly a quarter not taking this step. Even when suppliers were regarded as key to their business, nearly half of respondents had not checked or validated their supplier’s business continuity plans.

“The report concluded that most organization[s] sit at some point between the polarities of ‘no risk at any price’ and ‘lowest cost at any risk’ but the survey indicates that business continuity is still overlooked in supply chain decisions. ‘The findings also highlight that increased disruption is a reality not just a threat when pursuing such decisions, however the intelligent application of BCM [business continuity management] can help support organization take advantage of such supply chain optimization techniques, as part of an overall enterprise-wide resilience strategy.’ And, it says: ‘Perhaps, the greater challenge is in embedding business continuity considerations in strategic and operational business decisions; this requires cooperation across a broad coalition of resilience professionals to demonstrate the benefits of such thinking in the context of the organization’s risk appetite.'”

Surely it comes as no surprise that relying on suppliers from low cost countries — where infrastructure is marginal or inadequate — increases the risk of disruptions to the supply chain. Good business continuity plans (or risk management) plans can help mitigate adverse affects of disruptions. Those plans, however, primarily deal with disruptions that can be anticipated. Dealing with unanticipated disruptions, like the eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajokull volcano last spring, are another matter entirely. Carol McIntosh reminds us, “Automotive manufacturer Nissan Motor was forced to shut down three auto assembly lines in Japan because the factories ran out of tire-pressure sensors when a plane carrying a shipment from a supplier in Ireland was grounded [as a result of the volcano].” [“The supply chain disruptions you’ll never plan for,” The 21st Century Supply Chain, 22 December 2010]. McIntosh offers some suggestions about how to deal with the unexpected. She writes:

“Obviously, the first challenge is to realize that an event of some type has occurred or is about to occur. But even more significant, is the response. How quickly your company responds and just what that response is, may have substantial impact on the company’s performance and, possibly, its bottom line. That’s why it’s critical to have tools and processes in place to respond quickly to unanticipated events that aren’t covered by a mitigation strategy.

- These tools must deliver visibility across the supply chain and provide alerts when an event is imminent, they must also include analytics so users can understand the importance of the event and the impact it will have.

- Secondly, the tools must allow users to collaboratively simulate possible solutions, such as splitting orders, expediting orders and finding alternate sources.

- The next capability may well be the most important. Once simulations are created, they must be compared and contrasted to determine which one best meets corporate goals and objectives. Using a multi-scenario scorecard allows users to compare the possible solutions and measure the impact of each potential resolution on key corporate metrics.

“Consider these two possible solutions to a critical parts shortage. The first solution is to use existing inventory and split apart orders. Customers will not receive their full order, but they will at least receive part of it. A second possible solution is to expedite shipment of parts from an alternate supplier to your facilities, fill the orders, and then expedite shipment to your customers.”

For companies operating lean supply chains alternative sources of supply may not be available. For an example, read my post entitled The Split Second Disruption to the Supply Chain. In that post, I relate how Nokia was able to capture all excess chip manufacturing capacity during an unanticipated disruption leaving rival Ericsson out in the cold. McIntosh concludes:

“The first possible solution results in a decrease in on-time delivery and, potentially, a decrease in revenue for the quarter. The second, however, will result in an increase in cost of goods sold and a corresponding decrease in margin. How do you know which route to take? These results, compared against a given target and appropriately weighted, provide an overall score for each solution. Thus, an analyst can then use those scores to determine which scenario best suits corporate objectives. How you make those quick decisions and how well they align with corporate objectives can make or break a company’s bottom line.”

Patrick Lynch insists that some unanticipated risks can be discovered if “supply management professionals … use mitigation mapping and supply base profiling to effectively pinpoint previously undetected risks in the supply chain.” [“Build a Better Disruption Plan,” Inside Supply Management, December 2010]. Lynch continues:

“John F. Kennedy once said, ‘When written in Chinese, the word “crisis” is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity.’ … Cutting-edge new tools and processes, such as mitigation mapping and supply base profiling, are making their way into the profession. These tools help proactively identify and manage risk, changing the way supply professionals protect supply lines. … Today, we face new complexities — such as changes in regulations, enhanced security measures, protection of intellectual property (IP), and geography and modal limitations, among others. As supply management becomes more complex and supply professionals become more involved in C-suite issues, we may miss some potential problems before they occur if we do not take the time to map and assess potential risks.”

Lynch reminds us that being able to identify a risk doesn’t mean that you will always be able to eliminate it. His advice: “When You Can’t Eliminate, Mitigate.” He continues:

“It isn’t always realistic or cost-effective to eliminate all risks. After all, a certain amount of risk is inherent in doing business. It is possible, however, to identify and mitigate risk. A mitigation tool can provide interim approaches to neutralize the initial impact of an event, as well as provide you with a path to permanently mitigate any risks you uncover in your assessments. Supply management professionals … tend to react, and rather well. But, it’s what you do before the issue occurs that delivers the most value.”

The first tool that he identifies to help supply chain professionals identify and plan for disruptions is mitigation mapping. He explains:

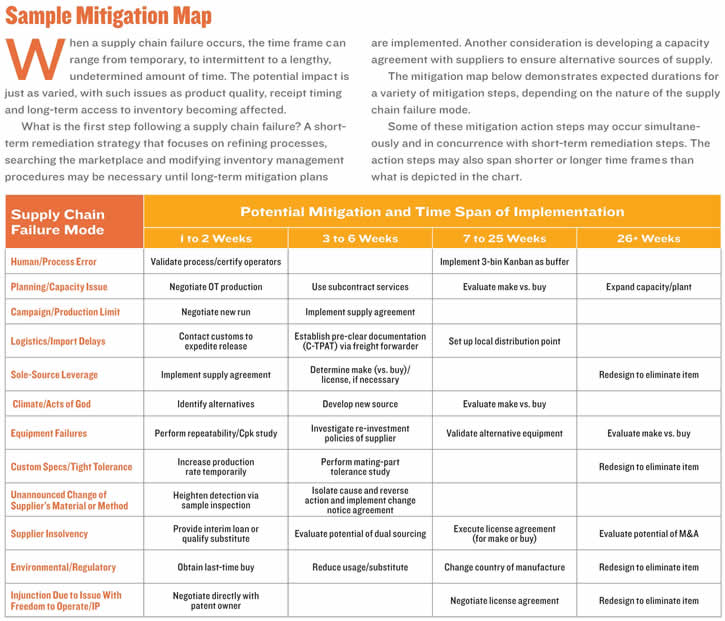

“A well-designed screening program raises the necessary red flags with minimal, cursory effort. Supply managers identify and assess potential risks during an initial, cursory review to determine which risks have a reasonable chance of occurring based on the nature of the product and supply line. The purpose of the mitigation map is to identify the risk, the expected duration and operational impact, and then identify corresponding short-term and long-term mitigation strategies. When you identify a potential concern, you gain a deeper understanding and can assign appropriate, proactive mitigation. The mitigation map technique allows you to see various perspectives and root causes, along with the solution, from a high level.”

To help you begin mitigation mapping, Lynch provides some “commonly overlooked external factors — each of which could lead to severe supply chain implications” — for you to consider:

- Undetected changes in suppliers’ processes and materials

- Process failures at suppliers’ facilities

- Lack of freedom-to-operate (limited access to IP used in the production process) or injunctive risk (legal restriction to doing business)

- Climate issues, acts of God, transit risk or labor strikes (both at home and abroad)

- Raw material depletion, scarcity and allocations

- Custom specifications, or tolerances that surpass industry standards

- Regulatory and environmental actions (REACH, RoHS, EPA)

- Materials required which are produced only as a byproduct of other processes

- Market/leverage shifts.

Below is a sample mitigation map that Lynch provided with his article.

The second tool recommended by Lynch is supply base profiling. He writes:

“Supply base profiling allows you to create transition plans to both remove risk and then to generate leverage plans that can create substantial savings. It also offers an objective approach to building a more robust supply chain by using comprehensive profiles that summarize data for all suppliers competing in a particular category. Used in conjunction with mitigation mapping, supply base profiling is extremely effective at quickly identifying and allowing you to deal with risk. The supply base profile should clearly identify the poor-performing, higher-risk and redundant suppliers. If possible, avoid carrying such suppliers. Provided the existing suppliers have these attributes, the supply management team must identify possible new sources and develop plans to transition from those suppliers. In addition, supply base profiling allows you to concentrate spend across the fewer, higher-performing and lower-risk suppliers. This concentrated spend may result in leveraged savings, as the remaining suppliers are in a position to offer lower prices to retain your business.”

Lynch underscores the importance of being constantly on the lookout for new sources of risk and disruption. He writes:

“As markets and technologies evolve, supply chain risk management programs must continue to evolve. No matter what industry you operate in, it’s important to remain vigilant to trends or issues that might affect any of your supply components now or in the future. It can be challenging, and possibly overwhelming, to take a deep dive to assess design and manufacturing processes, especially for suppliers that are critical to your product. … It pays to use concise and thorough tools such as mitigation maps and supply base profiling to proactively organize the issues at hand. The successful companies will be those that take swift, effective action when a supply disruption surfaces.”

Some disruptions risks (like terrorism) cannot be mitigated by stakeholders in the supply chain. Anti-terrorism measures are best enacted by a broad coalition of government players. Janet Napolitano, U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security, recently outlined measures that are being taken to help secure the global supply chain [“How to Secure the Global Supply Chain,” Wall Street Journal, 6 January 2011]. She writes:

“In today’s world, the very nature of travel, trade and commerce means that one vulnerability or gap anywhere across the globe has the ability to affect economic activity thousands of miles away. A consumer in Omaha can go online and buy a gift that is assembled in Thailand, from parts that were manufactured in China, shipped from Singapore through France, inspected at the port in Baltimore before finally arriving by plane, rail and truck in Omaha. The complex supply chain that consumers and businesses in the U.S. rely on every day is a target for those who seek to disrupt global commerce.”

Although terrorist attempts to disrupt the global supply chain have not been frequent, Napolitano provides several recent examples, most of which involved aircraft. She then continues:

“In 2011, the global community is poised to address the security of the supply chain that moves goods across the world and is a powerful engine of commerce, jobs and prosperity. A range of unpredictable and potentially catastrophic threats—from terrorist acts to natural disasters—presents substantial danger to this system. And regardless of where an event might occur, a significant disruption could ripple through the United States. The reality is that securing the global supply chain is part and parcel of securing both the lives of people around the world as well as the stability of the global economy. That is why, in partnership with the World Customs Organization, we seek to enlist other nations, international bodies, and the private sector to strengthen the global supply chain.”

Napolitano asserts that “there are three main elements of what we must do” to secure the global supply chain, they are:

“• First … prevent terrorists from exploiting the supply chain to plan and execute attacks. This means, for example, working with customs agencies and shipping companies to keep precursor chemicals that can be used to produce improvised explosive devices (IEDs) from being trafficked by terrorists.

“• Second … protect the most critical elements of the supply chain, like central transportation hubs, from attack or disruption. This means strengthening the civilian capacities of governments, including our own; establishing global screening standards; and providing partner countries across the supply chain with needed training and technology.

“• Finally, … make the global supply chain more resilient, so that in case of disruption it can recover quickly. Trade needs to be up and running, with bolstered security, if needed, as quickly as possible after any kind of event.”

Clearly in order to accomplish these three objectives there must be extensive collaboration and cooperation among supply chain stakeholders. Ms. Napolitano correctly asserts that the global economy cannot recover and grow if the supply chains that are its lifeblood get disrupted. She discusses some of things that the U.S. Government is doing in cooperation with other governments; then concludes:

“Together, the global community can make great strides on all of these fronts in 2011. Just as the nations of the world were able to make historic progress on enhancing international aviation security in 2010, so too can we make global supply-chain security stronger, smarter and more resilient this year.”

Every stakeholder in the supply chain needs to do its part. Like any chain, the supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link.