Nat King Cole used to sing about “those lazy, hazy, crazy days of summer” and concluded, “You’ll wish that summer could always be here.” Andrew Roberts is not so sure that world or business leaders share those sentiments. He writes, “What is it about the month of August? Why should we still persist in regarding it as a quiet time — with Congress in recess, business slowed down, and people on holiday — when so many world-historical events take place in this month? You can ignore the Ides of March, but history shows that it’s in the dog days of August that great events take place.” [“It’s August: Prepare for Cataclysm,” Wall Street Journal, 7 August 2012] Roberts continues:

“Ever since the Roman Senate proclaimed in A.D. 8 that the eighth month of every year be named after the Emperor Augustus (63 B.C.-A.D. 14), nephew and adopted heir of Julius Caesar, the month has seen a disproportionate share of cataclysmic events. In the last century alone, World War I broke out on Aug. 4, 1914, and Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland on the night of Aug. 31, 1939. World War II was only won with the dropping of two atomic bombs in August 1945.”

Roberts goes on to list well over a dozen other “20th-century conflicts sparked in August.” He then asks, “Might there be a reason why this month keeps cropping up when great men and great events collide?” He continues:

“In Europe and America, August is usually the hottest month of the year. The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Aug. 24, 1572 — a series of assassinations and mob attacks against French Protestants — will always stand as a terrible crime made much worse by the sultry heat that Paris had been sweltering under for three weeks. The city’s heat frayed tempers and gave the city a fetid, sinister feel even before the order for the wholesale massacre was given. Yet it hardly explains the turmoil that still takes place in the period after the invention of air conditioning. Another explanation might be that principal political decision-makers often take vacations in August, leaving less competent lieutenants in control. … Shakespeare writes in ‘The Tempest’ of ‘You sunburn’d sicklemen, of August weary,’ but the Grim Reaper never seems to weary of this month. So let’s show much more respect for these 31 days of regularly recurring cataclysms. Great world events very rarely, it seems, conform to Congress’s timetable.”

If you’re involved in supply chain risk management, you might want to shore up your company’s defenses before heading to the beach, the mountains, or the theme park. Douglas Kent, Vice President Avnet Velocity, Avnet Inc., reminds us, “Supply chains remain a ‘Risky Business’ for many organizations.” [“Supply Chain: It’s Still ‘Risky Business’,” EBN, 6 August 2012] He continues:

“There is no doubt that for many reasons, most organizations have an increasingly fragile supply chain that is riddled with potential risk. Over the past few years, we have seen significant events around the world that have only heightened the awareness of how detrimental risk can be to the business. This has caused supply chain risk management to become a paramount focus for many organizations. But the question on the minds of executives today is still: How do we take decisions on which of the possible risks to mitigate?”

That’s an excellent question to ask (especially, apparently, in August). Kent, however, reminds us that geopolitical risks aren’t the only threat about which companies should be concerned. He continues:

“Having a disaster recovery program or putting in place a high-level business continuity plan is simply not enough and seldom touches the risks stemming from risks that aren’t geopolitical in nature. How would a disaster recovery program aid in the resolution of a key supplier suffering from insufficient capital to fund an unanticipated growth in demand, for example? A robust process for calculating risk is helpful in moving the organization from simply addressing response capabilities to better assessing where in the supply chain we are most vulnerable. This process starts from a solid mapping of the current supply chain and identifying the potential risks.”

For a further discussion of supply chain mapping, see my post entitled Risk Management: Mapping Supply Chain Risks. Kent concludes:

“The application of the value-at-risk (VAR) measurement helps us assign a quantifiable number for the risk by the simple calculation: Probability x Impact = VAR. An understanding of the VAR will drive us to consider the ROI of any mitigation effort to either reduce the probability of the risk occurring (prevention) or the impact that the risk might have to our business (recovery). This powerful combination will help to set an organization on the right path to de-risking its overall supply chain.”

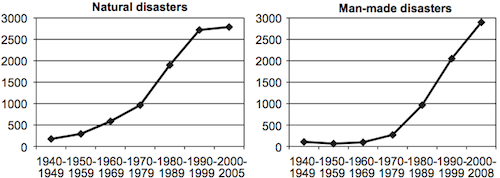

Most analysts agree that the data shows that disasters capable of causing supply chain disruptions are on the rise. Daniel Dumke writes, “Several factors help increase the vulnerabilities of today’s supply chains. When supply chain complexity increases (e.g., supply chain length, higher division of labor, …), the vulnerabilities also rise. Furthermore there is evidence that natural and man-made disasters are on the rise as well.” [“Assessing Vulnerability of a Supply Chain,” Supply Chain Risk Management, 10 October 2011] To underscore his point, Dumke published the following graphic which he took from a research paper entitled “Assessing the vulnerability of supply chains using graph theory,” written by Stephan M. Wagner and Nikrouz Neshat.

It would be interesting to see how many of those disasters occurred in August. Dumke writes, “Since natural- and man-made-disaster most often cannot be influenced directly, the authors argue that the focus has to be on reducing the vulnerabilities themselves.” In another post, Dumke reviews an article entitled “18 Ways to Guard Against Disruption,” that was written by D. Elkins, R. B. Handfield, J. Blackhurst, and C. W. Craighead and published in the Supply Chain Management Review in 2005. [“Ways to guard against Disruptions,” Supply Chain Risk Management, 17 October 2011] The study is useful because it identifies “18 best practices” that organizations can use to guard against supply chain disruptions. You might want to review the list of best practices before heading out the door on holiday.

“External orientation/future business (‘Strategic sourcing & advanced procurement’)

- ‘Screen and regularly monitor current and potential suppliers for possible supply chain risks.

- Require critical suppliers to produce a detailed disruption-awareness plan and/or business-continuity plan.

- Include the expected costs of disruptions and operational problem resolution in the sourcing total-cost equation.

- Require suppliers to be prepared to provide timely information and visibility of material flows that can be electronically shared with your organization.’

“External orientation/current business (‘Supply-base management’)

- ‘Conduct frequent teleconferences with critical suppliers to identify issues that may disrupt daily operations and discuss tactics to minimize these issues.

- Seek security enhancements that comply with the Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT), Container Security Initiative (CSI), and similar initiatives.

- Test and implement technologies to track containers.

- Conduct a detailed incident report and analysis following a major disruption.

- Create exception-detection/early-warning systems to discover critical logistics events that exceed normal planning parameters.

- Gather supply chain intelligence and monitor critical supply-base locations.’

“Internal orientation/current business (‘Real time operations management’)

- ‘Improve visibility of inventory buffers in domestic distribution channels at the part level.

- Classify buffered material by its level of criticality.

- Train key employees and groups to improve real-time decision-making capabilities.

- Develop decision-support tools that enable the company to reconfigure the supply chain in real time.’

“Internal orientation/future business (‘Strategic supply chain design’)

- ‘Develop predictive analysis systems that incorporate intelligent search agents and dynamic risk indices.

- Construct damage-control plans for likely disruption scenarios.

- Understand the cost trade-offs for different risk-mitigation strategies.

- Enhance systemwide visibility and supply chain intelligence by using improved near-real-time databases.’

Dumke indicates that none of the companies whose executives were interviewed for the report “had implemented all of the identified measures at the same time.” He concludes by noting that the authors suggest:

“Companies may want to use the best-practices list as a thought-starter to help them prioritize which supply chain risk management elements to adopt. For example, companies could develop an internal survey, based on the best-practice list, which would assess their supply chain risk management capabilities.”

Dr. Omera Khan, senior lecturer in logistics and supply chain management at the University of Hull, told the editorial staff at SupplyChainBrain that “globalization and outsourcing have combined in recent years to increase supply-chain risk substantially.” [“Meeting the Challenge of Rising Supply-Chain Risk,” 22 December 2011] The good professor didn’t indicate that August was a particularly troubling month, but she did say that “local disasters and political turmoil now have a global impact on buyers and suppliers alike.” She told the SCB staff, “We’re creating challenges and chaos … and over-complicating our supply chains. … As a result, risk has increased far more quickly than 20 to 30 years ago.” The article continues:

“Risk has become a critical topic for the boardroom, requiring a formalized approach that reverberates throughout the supply chain. … ‘What’s becoming quite evident here is that supply-chain risk management isn’t an issue that can be ignored,’ Khan says. ‘It needs to be led top-down, and filtered throughout the organization.’ Senior executives must embed a ‘supply-chain risk culture’ at all levels, making individuals accountable for the effort. An effective risk-oriented culture will combine the operational perspective, managing day-to-day affairs, with a strategic approach stretching over the next five to 10 years. … Change doesn’t happen overnight, says Khan. It involves more than the hiring of a chief risk officer. Key to any effective effort is the adoption of a demand-driven strategy, coupled with the ability to respond to immediate issues such as the sudden unavailability of critical components.”

With all that there is to worry about when it comes to supply chain risk management, you might wonder if risk management professionals ever really take a vacation.