Robert J. Bowman, managing editor of SupplyChainBrain, writes, “You have to empathize with anyone who’s responsible for managing the risks that accompany global supply chains. One moment you’re preparing for the spread of bird flu from Asia – then a hurricane strikes the Gulf Coast. So you shore up your network and people in that area – and an earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster hit Japan.” [“We Interrupt This Supply Chain …,” 27 February 2012] In Part 1 of this two-part series on preparing for catastrophes, we talked about supply chain risks that could affect the workforce. In this post, I’ll discuss how some analysts, including Bowman, recommend planning to face the challenges presented by catastrophes. Bowman asks, “How can a company guard against every possible calamity, the variety of which seems endless? Where does it even start?” He continues:

“As with any complex problem, you begin by identifying and measuring the specifics of your supply chain. The collection of basic data, both within and outside the company’s walls, is essential. Each factory must be profiled in detail, from its location to the number and nature of items produced there. At the moment disaster strikes a particular location, the buyer of goods or raw materials has to know precisely where it can obtain alternative sources of supply.”

Daniel Dumke believes the business world can learn some lessons from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) whose primary task is responding to natural disasters. [“Natural Disaster Management Planning,” Supply Chain Risk Management, 27 February 2012] In some ways, the task faced NGOs is much more difficult than that faced by businesses. They have the entire world to be concerned about and never know which part of the world will be affected next. Companies have specific, known locations to worry about. The only thing NGOs know for sure is that another natural disaster is going to happen shortly after the last one has occurred. Dumke bases his post on an article written by Marcia Perry, from the Department of Management, Monash University in Australia. [“Natural disaster management planning: A study of logistics managers responding to the tsunami,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 37 Iss: 5, pp. 409 – 433, 2007) Drawing from Perry’s paper, Dumke concludes, “Several factors are necessary to improve response activities.” They are:

-

“Preparedness in vulnerable regions, focusing on the ‘ability to respond quickly and appropriately.’

-

“Local involvement. The local authorities and population directly involved in a disaster also are ‘in the best position to respond immediately’ to a disruption.

-

“Coordinated needs assessment, which also includes local groups ensures that support can be given on efficiently where required

-

“Information sharing: ‘Emergency preparedness and response stages are driven by information.’ Therefore sharing information between the disaster response parties is an important factor to improve overall outcome.

-

“Logistics expertise and efficiency. Natural disasters often leave most critical infrastructure destroyed. To quickly support a large number of road access is of utmost importance. ‘Logisticians play an important role during the initial emergency period, they are often given limited authority to carry out their decisions. Frequently too, the assessment teams sent by humanitarian agencies to determine the needs of the affected population do not include logisticians. When logisticians are not included in the planning and decision-making process this causes delays in distributing relief.’ Also local logistics expertise should be leveraged to further foster the speed of delivery.”

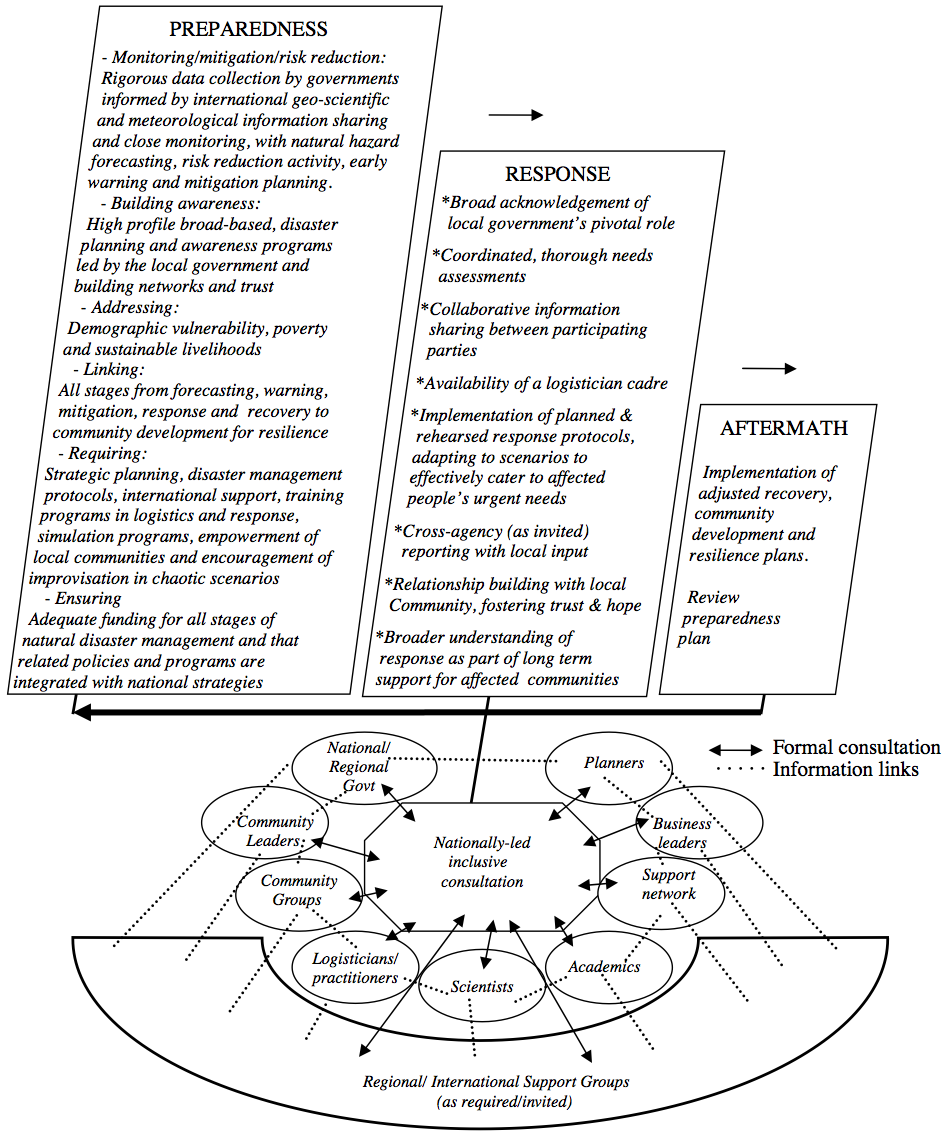

It’s not difficult to see how those factors could also help improve a corporate disaster response and continuity of business plan. Based on empirical observations and surveys, Perry developed a “model of effective natural disaster response management planning … that is holistic and inclusive.” The following graphic “summarizes the relevant stakeholders and tasks.”

Although the participants involved in disaster planning for a business would be different than those identified by Perry, if followed, her basic model certainly has some value for businesses. As Dumke concludes, the parts of the model that are “transferable [to] a business situation” include “the need for quick information [shared] by extensive communication and local knowledge and capabilities to deal with disasters swiftly.” The one caveat I would add is that good data and extensive communications are not generally available during a disaster. That’s why training people to respond at each site is so critical. Rarely will a company have the opportunity to rush in a team of troubleshooters to make the situation better. Suppose you do have good information? Patrick Brennan, chief executive officer of Supply Risk Solutions, told Bowman that “merely having that information in hand doesn’t mean you’re immune from the impact of a disaster.” Bowman continues:

“It’s human nature to respond to a crisis by preparing for its recurrence. We are, after all, supposed to learn from experience. If our house gets burgled, we’ll put better locks on the doors, and install an alarm system. But that tendency doesn’t always work at the level of a complex global supply chain. On the contrary, says Brennan, ‘it’s important to realize that events in [the] future might not be the same as in the past. You need to take a broad look at risk.'”

Part of the mitigation strategy for some companies is buying from numerous suppliers in varied locations. But Bowman asserts that “the question of how many suppliers to keep on hand for a particular item is never an easy one.” He explains:

“There are obvious efficiencies in paring down one’s suppliers to the bare minimum, chief among them increased vendor loyalty and lower prices. But a single-supplier strategy is risky business indeed – it can leave a company paralyzed for an unacceptably long period of time. Brennan doesn’t see a lot of companies retreating from the cost-driven strategy of supplier consolidation, but he does believe that risk management is becoming a more important element of any decision about building a solid supply base. Beware of achieving the illusion of supplier diversification, Brennan warns.”

Bowman points out that having a large number of suppliers in the same geographical location isn’t a resilient strategy. Nonetheless, he writes, “That scenario is becoming increasingly common, with the development of global technology centers in key parts of the world. Unless your problem is the failure of a single supplier, having another one next door isn’t likely to ensure the uninterrupted flow of product in the event of a major disruption.” He continues:

“There is, of course, one other step that has to occur before a company can implement a workable risk-management program: it has to care. Whether this attitude is occurring on a widespread basis is a point of some contention. Some multinationals have taken significant steps toward shoring up their supplier networks. But Jeff Karrenbauer, president of supply-chain planning consultancy Insight, Inc., recently wrote that a ‘majority’ of companies have spent little or no time planning for random acts of nature and other possible disasters. ‘That is astounding, troubling and frankly, a significant management failure,’ he said.”

Bowman reports that other observers are more sanguine about the state of risk management than Karrenbauer. For example, Jim Lawton, president and general manager of D&B Supply Management Solutions, told Bowman, “We’ve definitely seen an uptick in interest. What’s happened in the last year has woken people up to the fact that they need to have a better way of understanding and mitigating the impact of these disasters on their businesses.” Bowman continues:

“Whether that attitude has translated into wide-scale, meaningful action is another matter entirely. … The emerging science of supply-chain analytics can help. In Lawton’s words, it provides businesses with ‘some form of guided navigation’ – a means of making sense of that mountain of raw data. Managers can more easily sift through the data that they need to address the issue of the moment. The capability is contained in any number of technology platforms that address procurement, supplier relations and global trade management.”

Bowman cautions, however, “The complete answer doesn’t come wrapped in a piece of software.” He concludes:

“Businesses need to align their processes with the potential risks they face. Most of all, they need to achieve a level of agility that allows them to respond to any emergency that might occur. One way to achieve that capability is to carry out periodic drills, during which a company will respond to a particular mock disaster. In the process, they come to understand the role of each individual in the chain of command. That’s not something you want to be figuring out at the moment of crisis. According to Lawton, only a ‘very small’ number of companies engage in such exercises – but it’s a valuable way to ensure survival in a world of mounting uncertainty.”

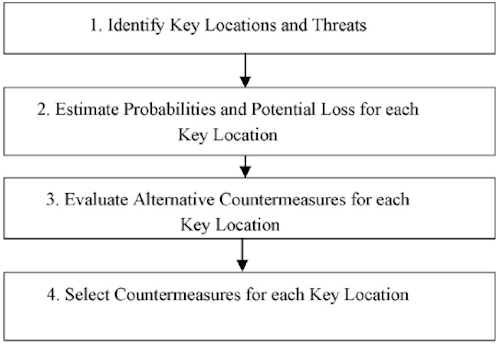

For some companies, the task may look so daunting that the first step feels a lot taking the first bite of an elephant. Back in 2009, Michael Knemeyer, Walter Zinn and Cuneyt Eroglu noted that as a “result of investments made in recent years to operate supply chains with fewer human and capital resources, especially inventory … there is … less ‘slack’ available in supply chains to deal with catastrophic events.” [“Proactive planning for catastrophic events in supply chains,” Journal of Operations Management, 27 (2), pp. 141-153, 2009] Knemeyer and his colleagues suggested that “proactively planning for these types of events should be a priority for supply chain managers.” They proposed a process that “builds upon an existing risk analysis framework by incorporating an innovative methodology used by the insurance industry to quantify the risk of multiple types of catastrophic events on key supply chain locations.” Jan Husdal praised this approach, claiming that it provides “a clear direction for further research and practical application as to how companies can evaluate and plan for catastrophic risk in supply chains.” [“Catastrophic events in supply chains,” husdal.com, 24 August 2009] The following graphic shows the planning process suggested by Knemeyer and his colleagues.

Daniel Dumke explains the process this way:

“The first step in the planning process is to identify key supply chain locations. A location is considered key if interruption of its operations results in a major disruption in the flow of goods in the supply chain. After finishing the first step, the manager should have a list of key locations, together with the major catastrophic events that should be considered. As a next step the probabilities have to be estimated. The authors suggest catastrophe simulation as a tool to estimate probabilities. … For the third step potential countermeasures are designed and selected in the next step for each key location. … To select the strategies the authors suggest simple expected loss comparisons.” [“Planning for the Catastrophe,” Supply Chain Risk Management, 11 July 2011]

Dumke concludes, “The suggested process should be suited for implementation within a company. Of course there are several simplifications which have to be analyzed prior to implementation. For instance, the authors suggest [using] scenarios (each with probability and impact). I believe that when starting a process implementation like this it might be sufficient to use plain probabilities.” If you’re interested in this topic, I suggest reading both the original paper and Husdal’s post about it.