I was recently contacted by Annabel Symington, Deputy Editor of Business Research for The Economist Intelligence Unit. She thought I might be interested in a new EIU report that “examines how companies manage risk and compliance activities, and reveals that few companies have the ‘big picture’ view needed for the effective management of these issues.” The report, entitled Ascending the maturity curve: Effective management of enterprise risk and compliance, was based on the findings of “a survey of 385 senior executives from the finance, risk, compliance and legal functions in six industries: financial services; healthcare; energy and utilities; logistics and manufacturing; and the public sector.”

Symington indicated, “The survey results showed that while companies understand the importance of an integrated risk and compliance strategy, many have short-sighted practices that end up becoming a costly and complex burden.” In this two-part series, I’ll discuss the highlights from the report. The full report can be downloaded by clicking on this link. Symington notes that “the research was sponsored by SAP” but “the Economist Intelligence Unit retained full editorial control of the research.”

In the introduction to the highlights, authors of the report state, “The report compares perception with reality, exposing the discrepancies between how executives view their risk mitigation capabilities and what they are actually doing.” There will always be differences in perception and reality regardless of the activity in which humans are involved. The problem, of course, is that, when perception and reality are vastly different, bad choices can be made and ill-conceived courses of action can be pursued. Highlights from the report cover ten areas. I’ll discuss the first five areas in this post and remaining five areas in the next. The first area involves the role of the Chief Risk Officer.

1. Chief Risk Officers need to earn respect from the business lines

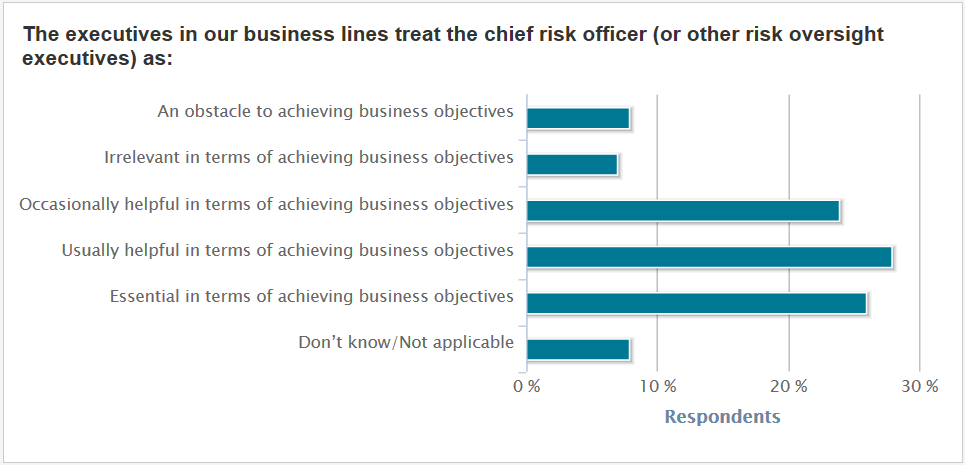

“An increasing number of organizations are making governance, risk and compliance a board issue by appointing high-ranking chief risk officers. Yet the contribution of many of these individuals is not recognised inside the business, new research from the Economist Intelligence Unit, done on behalf of SAP, suggests. Just 26% of the 385 executives surveyed said line [managers] felt the CRO was essential in terms of achieving business goals, and another 28% said the CRO is ‘usually helpful’.”

Face it CROs are looked upon like theater or food critics. Kenneth Tynan once wrote, “A critic is a man who knows the way but can’t drive the car.” In the case of CROs, they generally aren’t allowed to drive the car and the people they are trying to guide would rather pursue their own course even if it takes them amiss. The fact of the matter is, however, that a good CRO is like a GPS unit. The GPS unit may not be able to drive the car, but following its recommendations will generally get you where you need to be. The accompanying graphic concerning executive attitudes toward CROs clearly demonstrates that other C-level officers don’t yet appreciate the value of a good CRO.

Like every other C-level executive, the CRO must make a business case for why his function is important to the overall success of the organization. Part of the challenge faced by the CRO is that his (or her) responsibilities overlap traditional business silos and can create tension if not outright internecine conflict. That’s why EIU analysts are spot on when they conclude that CRO’s must “earn” respect from the business lines. The authors next examine the perceptions of executives most concerned with financial oversight.

2. Finance executives’ perception of risk differs markedly from that of other risk-related functions.

“Fraud, lawsuits, security breaches, acts of God – all are examples of risk events that can result in large losses. And they happen often. But even after risks surface, not everyone is aware of them. Finance executives in particular often have a rose-tinted view of how well their organizations are performing in this area, according to a survey of 385 executives by the Economist Intelligence Unit. Compared to colleagues in legal, risk and compliance functions, finance professionals are far more likely to say that their organizations haven’t suffered from significant risk or compliance failures. All of the executives came from the same pool of companies. So why the difference in answers? In part, it may reflect the fact that risk and compliance are a central concern of the other functions surveyed. As a result, finance may have a different idea of what ‘significant’ means. Or, information about risk and compliance issues is not being widely shared throughout the company. Either way, it’s a surprising lack of awareness from a group charged with monitoring the lifeblood of the business.”

I agree with the assessment that the results show “a surprising lack of awareness” from money managers. Surely finance executives recognize that significant profit reductions can result from fines and penalties when their companies fail to comply with regulations or requirements. Enterra Solutions® entered the supply chain optimization arena based on the belief that we could help reduce fines and penalties. Executives from Conair, with whom we developed the Enterra Supply Chain Assurance Platform™ (ESCAPE™), have, on numerous occasions, commented that Conair has been able to save a substantial percentage of its revenue previously lost to retailer chargeback fines and penalties while increasing customer service. Pointing out these kinds of savings is part of the business case that CROs need to make to financial executives and others. Legal executives should be co-opted into helping make the case since failure to comply with government regulations could be extremely detrimental to a company’s bottom line. The study goes on to report that some industries are more at risk than others.

3. Which industries are most likely to suffer from significant risk or compliance failures?

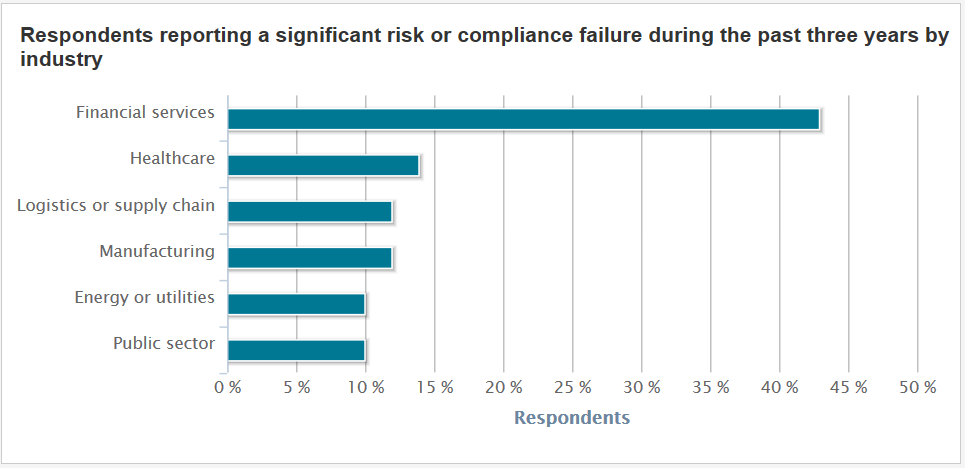

“The more complex and highly regulated the business, the more exposure it has to risk and compliance failures. … Not surprisingly, the financial services sector was far ahead of the other sectors in terms of failures. And despite the publicity surrounding the BP oil disaster, the energy and utilities sector reported the least.”

Once again, the attached graphic tells the tale best.

It makes sense that the more highly regulated an industry is the more likely it is to suffer a compliance failure. Complexity always increases risk. This is one area where technology can play a major, helpful role. Software programs can be used to keep track of and update regulations for companies. Software can also identify emerging conflicts and inform critical processes. As a result, good software programs can automatically alert decision-makers when problems arise so that actions can be taken to eliminate or mitigate compliance challenges. Technology can also be useful in helping to reduce corrupt practices that can result in devastating consequences. The next highlight discusses a common human foible — our willingness to fool ourselves.

4. Most people think they’re getting an “A” – until they see the “F”.

“It’s called the Lake Woebegone effect; the vast majority of people think they’re above average. That’s how executives responded when asked about their risk and compliance practices. In a survey of 385 finance, risk, compliance and legal executives by the Economist Intelligence Unit, almost half said that their company’s practices are consistent with the best in the industry. That is, until there is a failure. Once a risk event occurs, attitudes start to change. Executives in companies that have experienced failures are more likely to admit that their risk and compliance practices fail to measure up. Even then, many appear to be complacent. But the executives who rate their practices below average share one common trait: almost every one of them has learned a hard lesson from experience.”

For those who might be unfamiliar with the Lake Woebegone reference, it comes from the syndicated National Public Radio show called A Prairie Home Companion. Each week Garrison Keillor, the show’s creator and host, provides a news update from his fictional home town, Lake Woebegone, “where all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average.” To learn more about how companies are in denial, read my post entitled Supply Chain Risk Management and Disaster Mitigation: Part 1. In that post, I cite Curtis Barry, president of F. Curtis Barry & Co., who claims that many businesses believe they have a BC/DR plan in place, “but it’s often not the case.” [“Develop a master disaster plan,” Multichannel Merchant, 1 February 2011]. He writes:

“Natural or man-made, disruptions and disasters that could pose threats to the well-being of our employees, physical plants and business viability are more common than we think — and it’s human nature to be overconfident about our preparedness. … Concerns about costs, as well as the ‘it can’t happen to us’ mindset, prevent many companies from addressing these crucial issues.”

Barry is correct that overconfidence and denial can prove disastrous for a company whether you are talking about natural or man-made disruptions or failures to comply with regulations and/or policies. The fifth and final highlight I’ll discuss in this post addresses the fact that some parts of a company are more likely foster risky behaviors than other parts.

5. Where are the risks? Ask Dilbert.

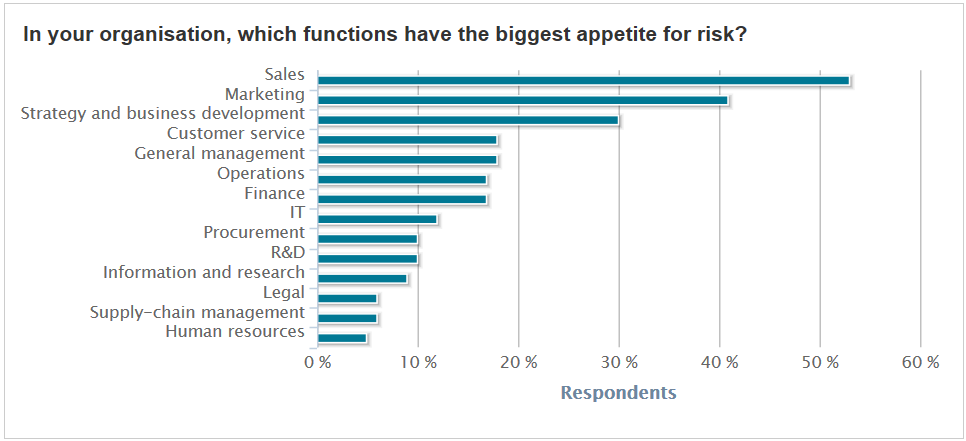

“In the comic strip Dilbert, a salesman says to an engineer: ‘I had to promise the customer that we could build the thing in a month even though you said it was impossible.’ The salesman’s statement contains a grain of truth. The same incentives that drive salespeople to hit or exceed their quotas often incent them to behave in risky ways. According to an Economist Intelligence Unit survey, finance, compliance, risk and legal executives say that the salespeople are the employees with the biggest tolerance for risk. Marketing is not far behind. The result holds across all industries, but especially in manufacturing and financial services.”

It comes as no surprise that sales and marketing are the two groups that demonstrate the riskiest behavior. After all, it’s marketing’s job to press the limits of hyperbole when trying to sell a company’s products. Sometimes those involved in marketing cross the line. For example, the Food and Drug Administration recently ruled that “sunscreens can no [longer] claim to be ‘waterproof,’ ‘sweatproof’ or act as a ‘sunblock.'” The FDA also ruled that claims for characteristics, like a sunscreen being ‘water-resistant,’ need to be clarified on the front of the bottle. [“FDA rules shine light on sunscreen labels,” by Jill Radsken, Boston Herald, 23 June 2011] We normally dismiss such claims as hype because we know that sales and marketing like to stretch the truth. The only surprise I saw on the list was that IT ranked lower on the risk list than I would have expected given all of the news about compromised systems that have been in the news lately.

Tomorrow I discuss the final five highlights from this excellent report.