In a post about the causes of major supply chain disruptions, analyst Bob Ferrari discusses insights gained from an E2open-sponsored survey conducted by Gatepoint Research. [“New Survey Data Reflecting on Causes of Major Supply Chain Disruption,” Supply Chain Matters, 7 November 2012] Ferrari reports that the research group “contacted over 200 supply chain executives, the vast majority of which had responsibilities of Director level and above, with 29 percent at Vice President or CxO level. Respondents for the most part residing in firms with revenues in excess of $1 billion. According to study authors, all the respondents participated voluntarily and none were engaged using telemarketing. Thus this study is a good representation of senior level perceptions and priorities concerning the managing of supply chain disruption.”

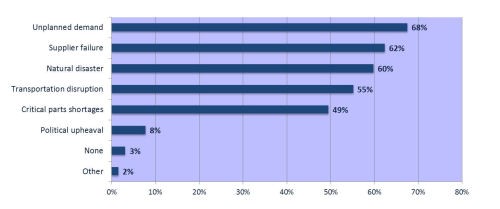

The topic of supply chain disruptions has gained prominence over the past decade as major disruptions have increased. They have been caused by everything from volcanic eruptions to floods to tsunamis to earthquakes. Surprisingly, however, natural disasters were not the causes of disruptions most mentioned by business executives. That spot went to unplanned demand. As can be seen from the following chart, natural disasters came in third.

Ferrari indicates that his own small sampling of executives agrees with the conclusions of the report. He writes:

“[During a live] webinar, I conducted an online, real-time interactive polling with a similar type of question. Listeners also ranked ‘unplanned demand’ and ‘supplier failure’ … as the highest categor[ies] of current disruption. In essence, supply chain executives and their respective teams are communicating that despite their best efforts at forecasting, planning or sensing customer product demand, unplanned demand remains as a challenge for coordinated and timely response. That is significant because it represents last-minute added business opportunities that supply chains are struggling to fulfill. Customers are indeed more demanding, and expect their suppliers to have adequate supply chain response management capabilities to fulfill last-minute needs. Similarly, despite the best efforts directed at monitoring suppliers, important information related to operational and financial conditions are apparently not being shared or a sugar-coated.”

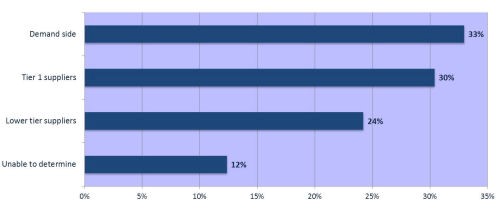

Ferrari’s comments underscore why so many analysts stress the importance of supply chain visibility and collaboration. Without good visibility and collaboration, customers are getting blind-sided downstream by consumers and upstream by suppliers. Since unplanned demand was the number one source of disruptions, it should come as no surprise that surveyed executives said that disruptions most often occurred on the demand side of their supply chains.

Ferrari notes that even though the demand side beat out the supply side as the primary location for disruptions, it was a tight race. If you add tier 1 and tier suppliers together, however, the supply side takes a substantial lead (54% to 33%) as to where disruptions occur. Ferrari continues:

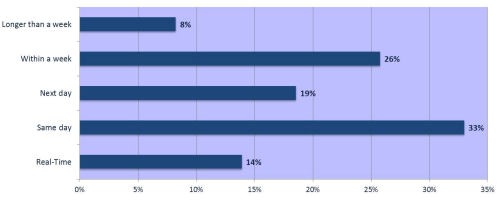

“Another set of questions probed on both awareness of a supply chain disruption and perceived actual response to the disruption. Nearly 34 percent of responders indicate that they were not aware of the disruption until more than a day after occurrence.”

In a business world where clock speed is increasing and decision time diminishing, a day’s delay in receiving pertinent information could prove disastrous. Most analysts believe that businesses need near real-time information to meet the challenges of today’s business environment. Ferrari mentions, that a follow-up question was asked on this subject, it was: “After awareness of the supply chain disruption, how quickly can you respond to most supply chain disruptions?” The following chart depicts participant responses.

After Ferrari reviewed the data, he concluded that it demonstrated a “need for improved sense and response capabilities.” In my discussions with large companies having global supply chains, I’ve learned that implementing improved sense and response systems is often seen as a challenge too difficult to tackle. They don’t know exactly what data they need or how to obtain it. Because the task is daunting, they assume the cost of such a system would also be daunting and the return on investment questionable. Few, if any, analysts would agree with that assessment. The risks are too great to simply rely on reactive strategy. Ferrari continues:

“When asked to prioritize needed improvements to address disruption over the next 12 months, a good indicator of highest priorities, the responses indicated a generally equal balancing among capabilities for increased visibility into tier one supplier inventories (38 percent), deeper partner connectivity and collaboration tools (30 percent and 36 percent respectively), along with the ability to invest in what-if scenario tools (30 percent).”

I agree that all of those corrective actions are advisable. Ferrari’s bottom line was this: “Supply chain disruption remains a key executive level concern, and disruption takes on many dimensions, including lost business and industry competitive dimensions.”

“In theory,” writes Paul E. Teague, “risk management seems such a simple concept.” [“The value of SRM in risk management,” Procurement Leaders, 12 November 2012] Obviously, Teague believes risk management is easier to discuss than to implement. He continues:

“When discussed in the abstract, it lends itself to all sorts of platitudinal phrases, like ‘pre-planning,’ whatever that means. But when a risk turns into an actual event, the platitudes become imperatives, and how well you and your suppliers planned beforehand and respond can determine the survival of your business.”

To strengthen his point, Teague provides an example of good “pre-planning” and preparation. He writes:

“American Airlines’ actions before and during the recent Hurricane Sandy provide a great role model for how exceptional supplier relationship management can turn risk-management theory into practice. The hurricane, which smacked the US East Coast in late October and moved swiftly inland, was the largest Atlantic hurricane on record. Encouraged by American’s procurement team, many of the airlines’ suppliers started taking action before the storm hit. For example, some suppliers of maintenance and aircraft parts were able to coordinate shipments to originate from alternate facilities and warehouses not affected by the storm. In another action, American worked with a third-party maintenance provider to suspend operations for two days leading up to the hurricane to assess on-going operations based on the aftermath. Planes were also routed away from the facility prior to the storm. The result was a drawn-out maintenance schedule, but the tactic kept the airline’s equipment and team safe. American’s catering suppliers already had disaster plans in place. The airline wrote that requirement into their contracts. The plans include provisions for backup generators, emergency contacts, and backup protocol for food safety if power fails. Additionally, American had a plan to put double the provisions on flights going into the Northeast so there would be food for return flights. One gate supplier even arranged to pick up employees across the New York City area who couldn’t get to work because public transit was down. For the crucial area of jet-fuel supply, American’s procurement team worked with the New York Port Authority, jet-fuel suppliers, pipelines, airport jet-fuel facilities, and other airlines to ensure there was enough fuel to fly for everyone. American also made sure there was enough fuel in places like Chicago for aircraft that left New York before the storm struck. In short, procurement analyzed the entire jet-fuel network to make sure planes could fly.”

Of course, each industry sector’s supply chains and supporting infrastructure are different. But Teague’s example is a good one. He writes, “None of that risk-management planning is easy. But American’s procurement team, including Sam Maher, who manages aircraft maintenance suppliers; Kyle Hansen, who manages caterers and food suppliers; Robert Lacy, who manages jet-fuel and gasoline suppliers; and John MacLean, vice president of procurement and supply chain, handled the disaster exceptionally well. Hats off to the entire team.” Teague’s colleague at Procurement Leaders, Steve Hall, writes, “Thinking about the cocktail of disruptive events that have been served in recent years might leave you short of breath.” [“The risks behind risk management,” 15 November 2012] He continues:

“Risk is one of those ideas that often isn’t relevant until you’ve experienced the consequences of a disruption, at which point you know exactly what steps you should have taken. Perhaps then the question for businesses should be whether they’ve used these events as a kicking off point to create a suitably effective strategy or whether they’ll always be trying to put out the latest fire.”

Hall goes on to suggest ways to create a “new mindset when it comes to thinking about supply chains” and the risks that could create major disruptions. His first point is that planning for large-scale disasters often draws attention away from smaller disasters that can have equally devastating effects. He writes:

“One point that my colleague Jonathan Webb is fond of underlining is that businesses spend a proportionally large amount of time preparing for events that might never occur and have relatively low impact. Consider a business that has a bunker network in case of terrorist activity, but no backup or maintenance on an IT system which, if it crashes, would mean the inventory management grinding to a halt. No suggestion here that preparing for larger events isn’t important, but the instance of smaller failures, perhaps more easily prevented or mitigated, but still disruptive and expensive, are frequently overlooked.”

Hall’s second point is that “keeping risk management to yourself” can sometimes become “a risk itself.” He explains:

“[Nick Wildgoose, Zurich Financial Services’ global supply chain product manager], related that in his work with the World Economic Forum and with Zurich he’s come across companies that ‘get it’ and have advanced risk management plans in place. However, he pointed out, whether they’re willing to share those ideas with others is another matter. Strong risk management is a competitive advantage and, so the thinking in some organizations goes, you’re best off guarding that knowledge. However, one reason that many, like Wildgoose, are keen to suggest that collaboration and sharing may be a valuable route is the potential for a better educated community. If businesses are going to embed risk management strategies deeper in supply chains they need to work with suppliers and share ideas that will help them, in turn, manage their suppliers.”

Hall’s final point is that companies need to look at both the supply and demand side when assessing and addressing risk. He writes:

“Supply chain disruption frequently comes from levels of the supply chain below the immediate supplier, which is a problem – you can imagine some of the panicked phonecalls during the Japan earthquake as purchasers tried to work out if they had suppliers in those regions. Supply chain visibility holds huge benefits for procurement, not least in better understanding the vulnerabilities it has on the supply side. On the flip side, the top procurement organizations have looked to align towards the customer side of the business and develop purchasing capabilities to help them anticipate and react to shifts in the market. A combination of alignment and intelligence from both sides of the business form the core of a value chain engineering strategy, but it also gives procurement the tools to be an effective manager of risk.”

Hall believes that a siloed approach to risk management by various corporate departments is a stillborn notion. He concludes, “The idea that procurement can act in a silo apart from risk management or that procurement can develop a risk management strategy that doesn’t factor in their own stakeholders is looking more and more redundant.” Since I’m one of those believers that the supply chain “is the business” and not peripheral to it, I agree with Hall that non-holistic approaches to supply chain risk management won’t be effective.