Daniel Dumke writes, “For several years now researchers [have] predicted, that in the future supply chains [will] compete, not companies.” [“Supply Uncertainty and Chain-to-Chain Competition,” Supply Chain Risk Management, 15 August 2011] If true, one must ask: what is the nature of that competition? Steve Banker asserts, “The ultimate point of supply chain management is to help companies be cost competitive while maintaining the bare minimum of inventory consistent with achieving a targeted service level.” [“The Catch-22 of Supply Chain Risk Management,” Logistics Viewpoints, 13 June 2011] Banker realizes, however, that there is a problem with that description of a competitive supply chain. He continues:

“Global outsourcing, reducing the number of suppliers you do business with, and using optimized planning to reduce inventory are common techniques companies use to accomplish a cost-effective supply chain. But all of these things that make for a lean and mean supply chain can also cause a supply chain to become brittle and break in the face of disasters. … Supply chain risk management says that you can avoid this outcome by having redundant factory lines in different geographic locations, using multiple suppliers, and carrying more inventory in locations around the world. These actions, of course, are the very opposite of what it takes to be a low-cost supply chain. This double bind is most acute for companies that compete mainly on price rather than service or product attributes. If these companies practice the prescribed risk management practices, they might find themselves losing a little market share year after year to competitors that don’t engage in supply chain risk management. Eventually, the company becomes an afterthought in the market. On the other hand, if a company runs a brittle, low-cost supply chain, the company may gain a little market share year after year until a disaster occurs. The firm then experiences a huge drop in market share all at once.”

In other words, being competitive means a company often finds itself in a Catch-22 situation. Retailers can help disrupt this unnerving situation by working with suppliers that maintain the most resilient supply chains. At least one study has shown that doing so is in a retailer’s own best interest. The study was conducted by Professors Biying Shou, from City University of Hong Kong, Jianwei Huang, from The Chinese University of Hong Kong, and Zhaolin Li, from The University of Sydney. They conclude, “that a retailer should order more … if its competing retailer’s supply becomes less reliable.” [“Managing Supply Uncertainty under Chain-to-Chain Competition,” Social Science Research Network, 27 August 2009] Their study examines “competition of two supply chains which are subject to supply uncertainty. Each supply chain consists of a supplier and a retailer.” The model may be simple, but the results are profound. They confirm what a number of supply chain analysts have been saying about the short-sightedness of perceiving the supply chain as a cost center that needs to be squeezed continuously to extract savings rather than a potential competitive advantage.

The authors note that “supply uncertainty is becoming a major concern in the global supply chain management.” Uncertainty can breed apprehension which results in less confidence. Professors Martin Christopher, from Cranfield University, and Hau Lee, from Stanford University, believe that lack of confidence can have a serious deleterious effect on supply chains. [“Mitigating Supply Chain Risk Through Improved Confidence,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 2004] They believe that increased supply chain visibility can improve confidence and help reduce uncertainty. In their abstract, they write:

“Today’s marketplace is characterized by turbulence and uncertainty. Market turbulence has tended to increase for a number of reasons. Demand in almost every industrial sector seems to be more volatile than was the case in the past. Product and technology life-cycles have shortened significantly and competitive product introductions make life-cycle demand difficult to predict. At the same time the vulnerability of supply chains to disturbance or disruption has increased. It is not only the effect of external events such as wars, strikes or terrorist attacks, but also the impact of changes in business strategy. Many companies have experienced a change in their supply chain risk profile as a result of changes in their business models, for example the adoption of ‘lean’ practices, the move to outsourcing and a general tendency to reduce the size of the supplier base. This paper suggests that one key element in any strategy designed to mitigate supply chain risk is improved ‘end-to-end’ visibility. It is argued that supply chain ‘confidence’ will increase in proportion to the quality of supply chain information.”

That conclusion is certainly not surprising to anybody who follows supply chain management thought leadership. What is surprising is that seven years on, we’re still talking about it with increased urgency. Supply chain uncertainty remains a problem and disruptions continue to occur. Christopher and Lee believe that lack of confidence creates a “risk spiral” that is often self-induced. They explain:

“The intangible lack of confidence in a supply chain leads to actions and interventions by supply chain managers throughout the supply chain, which collectively, could increase the risk exposure. A classic example of this is the potential reaction from the customer-facing end of a business. For example, if a sales team believes that order cycle and order fulfilment times are not reliable, they will devise their own means of addressing this. They may order stock so as to have supplies to support their key customers and put in phantom (i.e. their own private buffer stock) orders to secure supply, all causing inefficiencies.”

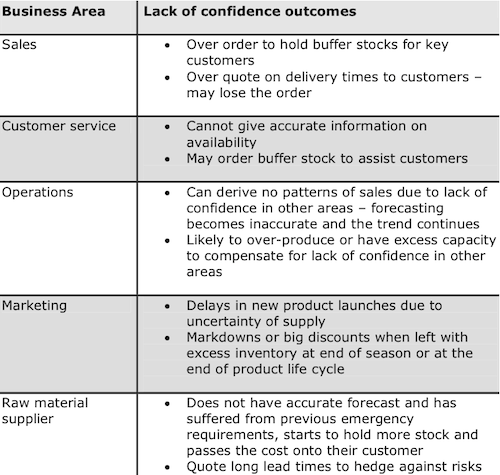

Christopher and Lee present a table in which they show other ways that lack of confidence results in a risk spiral.

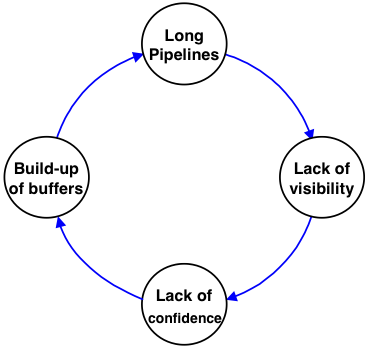

They depict the risk spiral itself this way:

Christopher and Lee assert that the “risk spiral exists everywhere, and the only way to break the spiral is to find ways to increase confidence in the supply chain. To do so, we need to understand the elements of the supply chain that can reduce the lack of confidence – visibility and control.” They continue their discussion with insights about visibility:

“Visibility — Confidence in a supply chain is weakened when end-to-end pipeline time, i.e., the time it takes for material to flow from one end of supply chain to the other, is long. The increased globalization of supply chains and the prevalent use of subcontract manufacturing and offshore sourcing can contribute to the length of time it takes to complete all the needed steps in the process. Associated with pipeline length is the lack of visibility within the pipeline. Hence, it is often the case that one member of a supply chain has no detailed knowledge of what goes on in other parts of the chain – e.g., finished goods inventory, material inventory, work-in-process, pipeline inventory, actual demands and forecasts, production plans, capacity, yields, and order status. The key to improved supply chain visibility is shared information among supply chain members. Traditionally companies have tended to subscribe to the view that ‘information is power’ and to interpret the phrase as meaning power is diminished if that information is shared. In fact in supply chains the reverse is true. If information between supply chain members is shared, its power increases significantly. This is because shared information reduces uncertainty and thus reduces the need for safety stock. As a result, the system becomes more responsive and, ultimately, could become demand driven rather than forecast driven. Mason-Jones and Towill (1997 and 1998) have demonstrated that ‘information-enriched’ supply chains perform significantly better than those that do not have access to information beyond their corporate boundaries.”

Increased access to information is of little value unless it is meaningful, timely, and can be acted upon. Christopher and Lee next to turn to that aspect of the supply chain which they call “control.” They write:

“Control — In addition to visibility, supply chain confidence requires the ability to take control of supply chain operations. Paradoxically, most supply chains do not have a great deal of control once the order is released. Hence, even if a supply chain manager has visibility of some part of the pipeline, he/she often could not make changes in a short time. For example, even if information is obtained on demand changes or on yield shortfalls, the supply chain manager may be helpless, since the suppliers may not be flexible enough to respond to late changes, or there are no expediting options available, or the production line is inflexible and production schedule changes are not feasible, etc. Semiconductor manufacturers are often faced with this problem of lack of control. In this industry, the long lead times required by foundries are such that, even if the manufacturer is made aware of sudden market demand changes, it takes a long time to respond so that the market opportunities are then missed.”

At Enterra Solutions we are working to provide clients with increased visibility so that they have more control over their supply chains. I wholeheartedly agree with Christopher and Lee that “the key to improved supply chain visibility is shared information among supply chain members.” Most manufacturers and retailers also appreciate the importance of visibility and control. I suspect that Banker agrees that improved visibility and control can help break the Catch-22 situation he described at the beginning of this post. He offers some other suggestions as well:

“There are risk management practices that any company can adopt that do not fall into the category of a double bind. For example, a firm can do contingency planning upfront on who will do what when a facility goes down. The company can look for components widely used across its products that would put significant revenues at risk if the supplier of that component was to experience difficulties; for these components, the company should look at dual sourcing. And companies can have preset playbooks in place for disasters that are more likely to occur. … For example, many retailers know that hurricanes are apt to strike the Gulf region every year during certain months. These retailers also know what products would be in demand when a hurricane hits, so they could carefully track hurricane forecasts and move the necessary inventory forward to key DCs before a hurricane strikes. But for companies that differentiate mainly on price, the core practices associated with supply chain risk management will continue to represent a Catch-22.”

The opposite of having a lack of confidence is having trust. Trust is increased as information is shared because, as Christopher and Lee write, “shared information reduces uncertainty.” Good contingency plans also help reduce uncertainty and increase trust because people understand what alternatives are available. Whether you call it a Catch-22 scenario or a risk spiral, it’s a situation that companies need to work hard to avoid.