“Innovation is a particularly sticky problem because it so often remains undefined,” writes Greg Satell. “We treat it as a monolith, as if every innovation is the same, which is why so many expensive programs end up going nowhere.” [“Before You Innovate, Ask the Right Questions,” If you have read many of my posts about innovation, you will know that I’m a big believer in the notion that good solutions begin with good questions. Satell is also true believer in that dictum. He quotes Albert Einstein who stated (perhaps apocryphally), “If I had 20 days to solve a problem, I would spend 19 days to define it.” I’m also a big believer in conducting experiments and using prototypes. Thomas Edison failed to find the right filament for his light bulb a thousand times. Edison didn’t see this as 999 failures, but 999 steps in a 1,000-step process to success. Asking the right questions and being willing to conduct numerous experiments are surer paths to innovation than sitting in a room with a group hoping somebody comes up with a bright idea. In this post, I’ll focus on the first of those methods — asking good questions.

The first set of questions you should consider asking is about your organization’s culture. Jack Uldrich, a futurist and best-selling author, believes that “most companies … only pay lip service to the notions of creativity and innovation.” [“25 Questions for the Truly Innovative Company or Organization,” School of Unlearning, 1 November 2012] He recommends that companies ask themselves a series of 25 tough questions concerning innovation to determine whether they are made of the right stuff. He asserts, “If you can’t successfully answer a majority of these 25 questions, your company probably isn’t doing enough to create an innovative culture.” His 25 questions are:

1. How does your company define innovation?

2. Is your company focused more on “innovative” projects or creating an innovative culture?

3. What is the role of senior leadership and managers? Do managers think of themselves as innovators? If not, why not?

4. Does innovation suffer because senior executives require “ironclad” assurances of success?

5. If asked, which current management practice does the most to stifle or kill creativity and innovation within the organization?

6. If failure is recognized as a necessary component of risk, how does your company deal with failure?

7. Is “innovation” listed in most employees’ job description? If not, why not?

8. How are employees encouraged or incented to be creative and innovative?

9. Who in the company is responsible for focusing on “what the organization doesn’t know?”

10. Who in the organization owns the “white space”?

11. Who in the company is responsible for throwing the organization off-balance?

12. Does your company have a system for challenging deeply held beliefs?

13. How does your company ensure discomforting information isn’t ignored?

14. What’s the “tomorrow problem” your company needs to begin working on today?

15. What’s the “can’t do” that needs to become the “can do”?

16. Where is an area where short-term profitability might need to be sacrificed in order to achieve long-term success?

17. How does your company “sanction the unsanctioned”? Are employees granted free time or “dabble-time” to work on innovative projects of their own choosing?

18. How easy is it for an employee to get “experimental funding”? If there is a procedure for such funding, what is the dollar limit?

19. Are new ideas allowed to openly compete for support? If so, how does this procedure work?

20. Has your company ever conducted a “post-mortem” on a company that failed to innovate fast enough? (e.g. Blockbuster, Borders, Kodak, etc.)

21. Have they ever been asked to conduct a pre-mortem on your own company?

22. Does your company have a regular speaker series?

23. How does the organization ensure outside voices are heard?

24. How easy is it for your customers to contribute ideas?

25. How does the company know it isn’t over-investing in “what is” at the expense of “what could be”?

Those are all excellent questions that will help you determine whether or not your company has an innovative culture. Unlike Uldrich, Satell assumes your company does have the right culture and focuses his questions on better defining a problem that needs to be solved. He writes:

“Defining a managerial approach to innovation starts with developing a better understanding of the problem we need to solve. I’ve found asking two basic questions can be enormously helpful.

“How well is the problem defined? When Steve Jobs, who was a master at defining a clear product vision, set out to build the iPod, he framed the problem as “1,000 songs in my pocket.” That simple phrase defined not only the technical specifications, but the overall approach. Unfortunately, some problems, like how to create a viable alternative to fossil fuels, aren’t so easy to delineate. So your innovation strategy will have to adapt significantly depending on how well the problem can be framed.

“Who is best-placed to solve it? Once Jobs defined the iPod problem, it was clear that he needed to find a disk drive manufacturer who could meet his specifications. But, sometimes the proper domain isn’t so cut and dried. Once you start asking these questions, you’ll find that they clarify the issues quite quickly. Either there is a simple answer, or there isn’t.”

The answer to Satell’s second question determines the “domain” in which the problem should addressed. If the answer to a challenge isn’t simple, then extensive experimentation is probably the next step in process. More on that topic tomorrow. Satell claims that once you’ve asked the right “framing questions” you are in a much better position to “determine which approach to innovation makes the most sense.” Satell offers a two-by-two matrix (shown below) for helping you select an approach. The approach selected depends on how well a problem has been defined.

As you can see from the matrix, the less well defined a problem is the more experimentation is likely to be needed. Satell discusses each of the quadrants beginning with Basic Research. He writes:

“Basic Research: When your aim is to discover something truly new, neither the problem nor the domain is well defined. While some organizations are willing to invest in large-scale research divisions, others try to keep on top of cutting edge discoveries through research grants and academic affiliations. Often, the three approaches are combined into a comprehensive program. … Breakthrough Innovation: Sometimes, although the problem is well-defined, organizations (or even entire fields) can get stuck. For instance, the need to find the structure of DNA was a very well defined problem, but the answer eluded even the most talented chemists. Usually, these types of problems are solved through synthesizing across domains. Watson and Crick solved the DNA problem by combining insights from chemistry, biology, and X-ray crystallography. Many firms are turning to open innovation platforms such as Innocentive which allow outsiders to solve problems that organizations are stuck on. … Sustaining Innovation: Every technology needs to get better. Every year, our cameras get more pixels, computers get more powerful and household products become ‘new and improved.’ Large organizations tend to be very good at this type of innovation, because conventional R&D labs and outsourcing are well suited for it. … In essence, great sustaining innovators are great marketers. They see a need where no one else does. … Disruptive Innovation: The most troublesome area is disruptive innovation, which target light or non-consumers of a category and require a new business model, because the value they create isn’t immediately clear.”

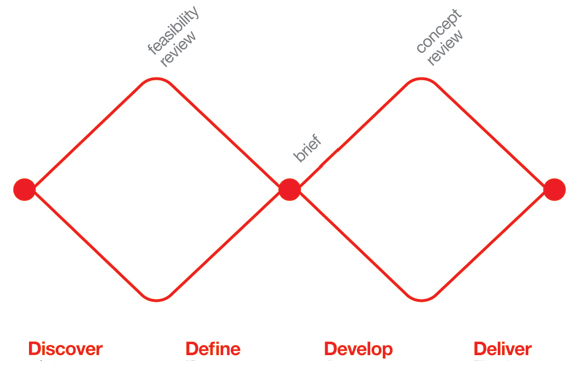

Satell makes it clear that, “while focus is important, no company should limit itself to just one quadrant.” He concludes, “It’s important to develop an effective innovation portfolio that has one primary area of focus, but also pursues other quadrants of the matrix and builds synergies between varied approaches. Innovation is, above all, about combination.” Richard Veryard calls this “challenge-led innovation.” [“Challenge-Led Innovation,” Demanding Change, 1 December 2012] He offers another way of looking at the same characteristics contained in Satell’s framework. It is a framework promoted by the Design Council. They call it the ‘double diamond’ design process model.

Veryard writes, “The first diamond is devoted to clarifying the problem or requirement, and the second diamond is devoted to solving a well-defined problem. If the challenge-led approach starts from a well-defined problem, then it is just doing the second diamond.” Another way of interpreting the model is that the first diamond involves the activities discussed by Satell and the second diamond focuses more on prototyping and experimentation. Regardless of the model you like best, the bottom line remains the same. The better the questions you ask at the beginning of the process the better the solutions are going to be in the end.