Humans have been rightly labeled social animals. Of course, humans aren’t alone. According to an entry in Wikipedia, “A social animal is a loosely defined term for an organism that is highly interactive with other members of its species to the point of having a recognizable and distinct society. … The term ‘social animal’ is usually only applied when there is a level of social organization that [has] permanent groups of adults living together, and relationships between individuals that endure from one encounter to another.” If you like that definition, humans are social animals and you could argue that ants aren’t. Ants have a highly evolved societal structure and exhibit extraordinary swarm behavior but they don’t have enduring individual relationships. Enduring individual relationships are critical for social animals. In the age of information, we have learned a lot about social connections and networks. The World Wide Web real came of age when Web 2.0 (the so-called) social web emerged along with sites like MySpace and Facebook.

Businesses, of course, have long had an appreciation for connections. Great sales people became “great” because they managed to generate a personal network of loyal customers. Companies are now trying to discover “how to decode new data about our online relationships, hoping for profitable insights” [“What’s a Friend Worth,” by Stephen Baker, BusinessWeek, 1 June 2009 print issue]. Baker writes:

“A question: If you have 347 followers on the Twitter microblogging service, what are the chances that they’ll click on the same online ad you clicked on last night? Advertisers are dying to know. Or, say you and a colleague exchange e-mails on a Saturday night. Can managers assume that you have a tight working relationship? Researchers at IBM and Massachusetts Institute of Technology are investigating.”

Baker points out that relationships are changing because we now have tools that allow us to find and connect with people from our past who have not remained within our relatively close circle of friends. He notes that even casual encounters, like an exchange of business cards, “can lead to an invitation, sometimes within minutes, for a ‘friendship’ on LinkedIn or Facebook. And unless we sever them, these ties could linger for the rest of our lives.” Baker wonders if such “friendships” really mean anything? If they do, exactly what is it?

“Companies armed with rich new data and powerful computers are beginning to explore these questions. They’re finding that digital friendships speak volumes about us as consumers and workers, and decoding the data can lead to profitable insights. Calculating the value of these relationships has become a defining challenge for businesses and individuals. Marketers are leading the way. They’re finding that if our friends buy something, there’s a better-than-average chance we’ll buy it, too. It’s a simple insight but one that could lead to targeted messaging in an age of growing media clutter.”

Baker notes that companies are not only interested in social networks for marketing purposes they are also interested in employee relationships “with an eye to quickening the flow of knowledge and the generation of ideas within their ranks.” IBM is one of the companies conducting relationship studies. One study “concluded that employees who forged tighter e-mail connections with their boss brought in on average $588 more in monthly revenue.” Baker asserts, however, “for most of us, the business value of networked friends is tied to a third area, personal opportunity.” In other words, the connections that make great salesmen great remain important. He continues:

“In addition to companionship, friends online represent a turbocharged Rolodex for entrepreneurs and job seekers inside and outside companies. These collections of contacts expand social horizons, keeping us in touch with more people who can provide ideas, answers, business leads, and even legal advice. Those who master these connections stand to win a big edge: the connections and brainpower of a large team.”

All of this may seem rather intuitive, but Baker underscores the fact that we are now generating loads of data that has never before been available about our relationships.

“Duncan J. Watts, a Columbia University sociologist now on leave and heading a research unit at Yahoo!, marvels at the change. ‘When I started network research 12 years ago, we had virtually no data,’ he says. Now he and his team can study the network behavior of 295 million e-mailers and legions of the 200 million Facebook users. For social scientists, Watts says, this flood of data could be as transformative as Galileo’s telescope was for the physical sciences: ‘It gives us a new understanding of our world and ourselves.'”

The biggest challenge emerging from the computer age is information overload. Baker continues:

“Now we’re swimming in information. We can call up nearly every bit of news, music, and entertainment we want on demand. In fact, there’s so much of it that we need filters to block the boring or irrelevant stuff and help us find the bits we need or desire. This has created what many call the ‘Attention Economy.’ Says Bernardo A. Huberman, director of the Information Dynamics Laboratory at Hewlett-Packard: ‘The value of most information has collapsed to zero. The only scarce resource is attention.’ So how do we figure out where to direct it?”

This challenge is not new to the intelligence community. It has understood from time immemorial that information is only valuable if it can be turned into actionable intelligence that reaches the right decision maker at the right time. Businesses are now trying to reach the right consumer with the right message at the right time. That’s where friends and relationships come into play.

“They’re our trusted sources. At least a few of them know us better than any algorithm ever could. Little surprise, then, that the companies most eager to command our attention are studying which friends we listen to. Online friendship is a hot focus for Facebook, Google, and Yahoo. They joust to hire leading sociologists, anthropologists, and microeconomists from MIT, Harvard, and Berkeley. Microsoft just established a research division focused on social sciences in Cambridge, Mass. Statistically, friends tend to behave alike.”

The problem, of course, is that all friends are not alike. Friends in a close circle have a lot more in common than those from a broader circle of Facebook friends. That is one reason, Baker points out, that “for all its popularity, Facebook has yet to prove itself as an advertising platform.” We all know that most online ads aren’t clicked; nevertheless, the number of people viewing them is staggeringly high so that “even a small boost [in the number of people that click on them] can make a big difference.” That is why so much research is being done about social networks. Baker concludes:

“All of networked humanity mingles in this vast marketplace, trading information, creating alliances, doing favors. We may not think of our connections in such mercantile terms. But for business and individuals alike, the value in online friendship is poised to grow.”

Companies that advertise online all dream of creating an ad or a promotion that goes “viral.” Washington Post columnist April Witt touches on this subject [“Going Viral,” 31 May 2009]. Witt writes:

“Scientists theorize that one reason humans need outsize brains is to store social information. Humans are inherently social creatures, evolutionarily wired to connect with one another and respond. Monkey see, monkey learn, monkey do. Just a decade ago, social scientists were lamenting that Americans were becoming dangerously disconnected from family, friends, neighbors and the civic square. It seemed as if everything from democracy to human happiness was threatened by ‘cocooning,’ Americans’ growing inclination to hole up at home alone watching oversize televisions and fiddling with their then-newest electronic toy: the personal computer. Today, the work of a social scientist named John Kelly is helping illuminate what has really happened to social networking in the age of the Internet. Blogs and other online forums have become the new bowling leagues and Rotary Clubs where humans gather and share social knowledge.”

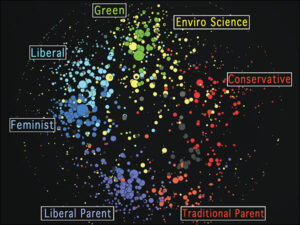

In other words, we may be bowling alone, but we are blogging together. Witt’s article is accompanied by an interesting graphic that visually shows some of the work being done by a social scientist named John Kelly. His work, Witt asserts, is helping illuminate what has really happened to social networking in the age of the Internet. Kelly uses graphs to map the blogosphere. Each blog or traditional source of information, such as a news site, appears on a graph like a star in a dark sky. The more influential the blog the brighter its star. Blogs that cluster around particular ideas, share information sources and link to one another appear like galaxies. (Graph from Kelly’s business Morningside Analytics) One of the interesting graphs created by Kelly’s company involved the blogosphere in Iran. Witt explains:

In other words, we may be bowling alone, but we are blogging together. Witt’s article is accompanied by an interesting graphic that visually shows some of the work being done by a social scientist named John Kelly. His work, Witt asserts, is helping illuminate what has really happened to social networking in the age of the Internet. Kelly uses graphs to map the blogosphere. Each blog or traditional source of information, such as a news site, appears on a graph like a star in a dark sky. The more influential the blog the brighter its star. Blogs that cluster around particular ideas, share information sources and link to one another appear like galaxies. (Graph from Kelly’s business Morningside Analytics) One of the interesting graphs created by Kelly’s company involved the blogosphere in Iran. Witt explains:

“Collaborating with Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, Kelly helped map the blogosphere in Iran. In addition to the predictable networks of secular reformists and conservative Islamists, the next largest cluster of bloggers in Iran focused not on religion or politics, but on romantic poetry. ‘What’s so great about mapping the blogosphere is you feel a little bit like Magellan sailing around the world seeing strange lands for the first time,’ Kelly said.”

Iran has a large blogosphere. If you want to learn more about Iranian bloggers, I highly recommend a book by Nasrin Alavi entitled We Are Iran. Online connections have proven to be extremely important in many repressed nations. They are also important for emerging market countries, which is why I make connectivity a major theme in my discussions about Development-in-a-Box™. The more we learn about networks, especially social networks, the better able we’ll be to answer Stephen Baker’s question, “What’s a Friend Worth?”