To what, you might ask, does the term “Tetherless World” refer? Currently, the Tetherless World is mostly a concept. According to Wikipedia, It involves a world in which information can be accessed “at any time and place without the need for a ‘tether’ to a specific computer or device. Researchers envision an increasingly web-accessible world in which personal digital assistants (PDAs), cameras, music-listening devices, cell phones, laptops, and other technologies converge to offer the user interactive information and communication.” Other concepts that are associated with this movement are artificial intelligence and the semantic web. At a recent conference I attended, Professor James A. Hendler, the Tetherless World Professor of Computer, Web and Cognitive Sciences Director at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Institute for Data Exploration and Applications, spoke on the subject. He entitled his presentation, “We are the Web: The Rise of the Social Machine.”

The social machine to which he refers involves the combined contributions made by Internet users. Knowingly and unknowingly Internet users contribute to growing online databases that can be accessed by both human researchers and cognitive computing systems, like IBM’s Watson computer and the Enterra Solutions® Cognitive Reasoning Platform™ (CRP). Technology can help organize and make sense of all of this data. Hendler drew upon Sir Timothy John Berners-Lee, best known as the inventor of the World Wide Web, for a definition of a social machine. Berners-Lee wrote:

“Real life is and must be full of all kinds of social constraint – the very processes from which society arises. Computers can help if we use them to create abstract social machines on the Web: processes in which the people do the creative work and the machine does the administration … The stage is set for an evolutionary growth of new social engines.”

The part of that definition that excites Hendler and other likeminded thinkers is Berners-Lee’s assertion that these social machines will embrace processes that unleash the creative juices of Internet users. As Berners-Lee suggests, the administration of those processes is best left to machines because, as you are well aware, not all human contributions are of equal value and all information found on the Internet is not accurate. Hendler calls this conglomeration of data a “blur.” Rather than being discouraged by this blur, Hendler recommends that we embrace it. The blur provides the “Wiki” world the ability to capture human wisdom and insights using technology. He also states that it is technology that helps prevent humans from spoiling those insights through defacement or vandalism. He reports that Wikipedia uses software robots to automatically “reverse obvious defacement immediately. Moreover, there are hundreds of people who spend a little time each day watching the list of recent changes on Wikipedia.” As I noted, in a previous post entitled, “Cognitive Computing and Human/Computer Interactions,” this kind of human/computer cooperation offers the surest path to progress in the future.

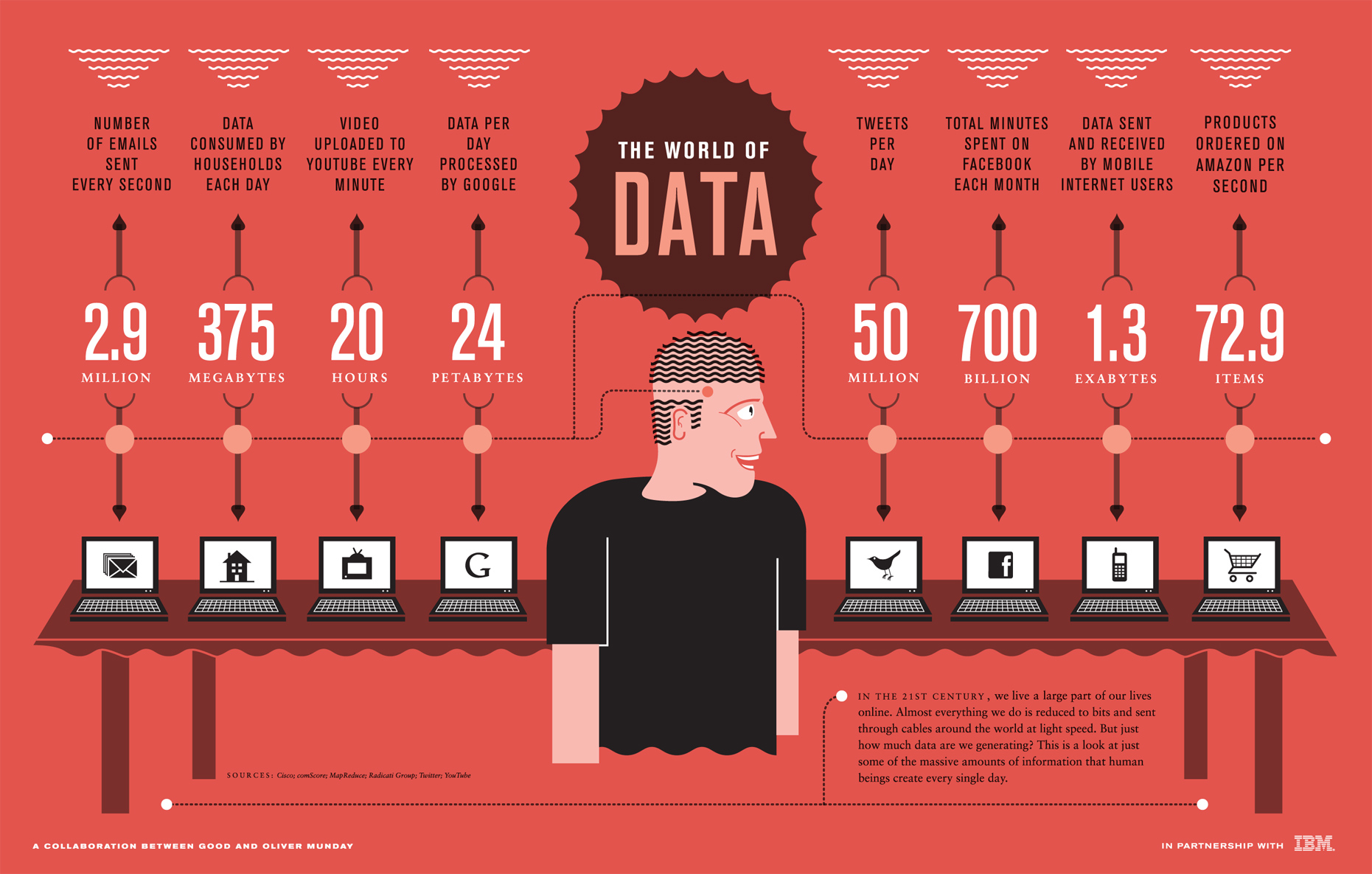

Since a social machine is defined as a process that can be used by a multitude of individuals, Hendler notes that many of today’s most popular websites, like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Flickr, fit that description. Each of these sites produces a mountain of data each day. To make that point clearer, Hendler displayed the following IBM infographic about data.

Hendler points out that it takes both time and effort to create all that data. Knowing that all that time and effort are already being expended, Hendler says that it begs the question, “Can we create technologies that make it possible to harness portions of that time and effort to help solve real-world problems?” He asked the audience to imagine the progress that could be made if “hundreds of millions of people” were able to effectively network together and, using available databases from science, governments, non-governmental organizations, etc., apply their brainpower to cure disease, feed the hungry, or empower the powerless. This sometimes happens by “accident” he claims. For example, Hendler noted that the many entries made by Internet users each day help improve things like Optical Character Recognition and semantic context. But “accidental” collaboration isn’t as purposeful as Hendler believes things need to be. He notes that a more purposeful way to get strangers to collaborate is through online games. Researchers are hoping, for example, that online gamers can help hasten the development of things as esoteric as quantum computing. Hendler believes there are other ways to harness human knowledge for problem solving as well. He noted:

“One new thing happening in Science, emphasized by a project such as Galaxy zoo, is using many many non-scientists help scientists solve hard and important projects – there is a huge opportunity for new technologies that can help us manage the scientific, engineering and even social problems facing our world. It is a huge area for new tools and technologies to be deployed.”

Galaxy Zoo is way for non-scientists to help astronomers classify galaxies. Even the creators of the program were startled by its success. Its website explains:

“It all started back in July 2007, with a data set made up of a million galaxies imaged by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, who still provide some of the images in the site today. With so many galaxies, we’d assumed it would take years for visitors to the site to work through them all, but within 24 hours of launch we were stunned to be receiving almost 70,000 classifications an hour. In the end, more than 50 million classifications were received by the project during its first year, contributed by more than 150,000 people. That meant that each galaxy was seen by many different participants. This is deliberate; having multiple independent classifications of the same object is important, as it allows us to assess how reliable our results are.”

That’s a great example of harnessing human knowledge for problem solving. The uses of such harnessed efforts are only limited by the imagination. Hendler notes that there are already a number of different Web 2.0 communities that have proven the effectiveness of networks. He identified five: blogs; Wiki, Question/Answer sites; social networks, and HFS. To effectively harness the potential of these communities, Hendler insists that you must understand several characteristics associated with each of them; characteristics such as: dynamics, trust, and governance. He noted that the dynamics of each community differ. They have different incentives for participating. We don’t know how online and offline flows of information differ between community members. Most importantly, he states, “We can no longer assume an expert —> novice continuum.” He is not sure, however, what replaces that continuum. Because the value of data found on the Web varies greatly, trust (and distrust), Hendler notes is a major concern. The objective of the Tetherless World is to share information, but sharing untrustworthy information is probably worse than not sharing at all. Finally, he states that governance is a critical factor. You would think that a group pushing for a Tetherless World would eschew governance; but, you’d be wrong. Just like traffic laws aid the flow of traffic, Internet governance can aid the flow of information. He notes, for example, that Wikipedia invokes “a lot of rules and privileged people to adjudicate/enforce” those rules.

In the end, Hendler admits that we are only at the beginning of the path that leads to a Tetherless World. Among the challenges that lie ahead are technological challenges. He notes that it costs a lot to build and support a scalable, governed platform. He insists that designing a game with a purpose (GWAP) is “still a black art and a large programming challenge.” Beyond games, he indicates we still need to understand how to “create tools that a community can use by itself.” In conclusion, he addressed one final question: “How do we define Social Machines more rigorously?” To that end, Hendler stated we need to create:

- Tools that allow groups of users to create, share, and evolve a new generation of open and interacting social machines.

- Underlying architectural principles to guide the design and efficient engineering of new Web infrastructure components for this new generation of social software.

- Mechanisms to guarantee that use protocols are explicit and conform to the relevant social policy expectations of users.

If these challenges can be successfully met, Hendler believes we can make enormous advances in fields like analysis and theory; engineering and technology; social science and communications; and economics and law. “We are on the cusp of a new technology,” he insists, “[that will] create Web-based systems that will transform society. … There’s a lot of important science to be done. [Nevertheless,] this is a truly interdisciplinary challenge in which computing, social science, informatics, and communications work [are] all required.” I believe that cognitive computing systems will play a significant role in making this vision a reality. Such systems punch above their weight since they both assist human decision makers and can learn on their own.