A year ago, New York Times‘ columnist Thomas Friedman wrote:

“You’ve heard that saying: As General Motors goes, so goes America. Thank goodness that is no longer true. I mean, I wish the new G.M. well, but our economic future is no longer tied to its fate. No, my new motto is: As EndoStim goes, so goes America. EndoStim is a little start-up I was introduced to on a recent visit to St. Louis. The company is developing a proprietary implantable medical device to treat acid reflux. I have no idea if the product will succeed in the marketplace. It’s still in testing. What really interests me about EndoStim is how the company was formed and is being run today. It is the epitome of the new kind of start-ups we need to propel our economy: a mix of new immigrants, using old money to innovate in a flat world.” [“Just Doing It,” 17 April 2010]

Although smart people understand the value of entrepreneurs (regardless of the entrepreneur’s race, creed, color, or country of origin), the fact remains that minorities face greater hurdles than white males when it comes to starting a business. “Minority-owned businesses have long faced barriers when it comes to access to credit,” writes Emily Maltby. “And even today, racial discrimination may still be to blame.” [“Minority Entrepreneurs Still Face Bias, Prof Says,” The Wall Street Journal, 10 March 2011] She continues:

“That’s the viewpoint of Robert W. Fairlie, professor of economics at the University of California Santa Cruz, who testified recently at a Senate hearing on the topic. Discrimination, he concluded, is the reason why minority-owned firms applying for loans get rejected twice as much as their non-minority counterparts. Fairlie, who analyzed Federal Reserve data from 2003, also found that minority firms that do obtain loans pay one-and-a-half percentage points higher interest rates than white-owned firms. Such disparities held true even after accounting for variables concerning the owner (such as age, experience and education) and the business (including creditworthiness, size, industry, age and location). ‘Racial discrimination in lending practices,’ he said in prepared remarks, limits ‘the ability of minority entrepreneurs to obtain financial capital.’ Racial discrimination, Fairlie noted, isn’t the only reason for the high rejection rate at the banks. Personal wealth is also a major factor. Minorities are hampered by low rates of home ownership and lower levels of home equity. The median net worth among Latino families is $13,375, and among African-American families is $8,650– a vast disparity from the median $113,822 held by non-minorities, according to Census data he cited.”

Banks are understandably cautious as the economy tries to recover from a severe recession whose onset was caused by subprime loans. The old adage “once burnt twice shy” comes to mind. But Professor Fairlie notes that discrimination could be found long before the economy turned bad. No one argues that banks should make bad loans, but Fairlie’s argument, like Friedman’s, is that minority-owned businesses are good for America. Maltby concludes:

“Despite the gloomy statistics on access to capital, minority-owned business ‘make enormous contributions to the U.S. economy,’ Fairlie said in his testimony. Minority-owned businesses produce more than $1 trillion in total sales, employ 6 million workers and have an annual payroll of $168 billion, he said. ‘Restricting minority business growth ultimately limits total U.S. productivity, job creation and innovation, which are essential for getting our economy back on track,’ Fairlie said. ‘There remains a lot of untapped potential among this group of firms.'”

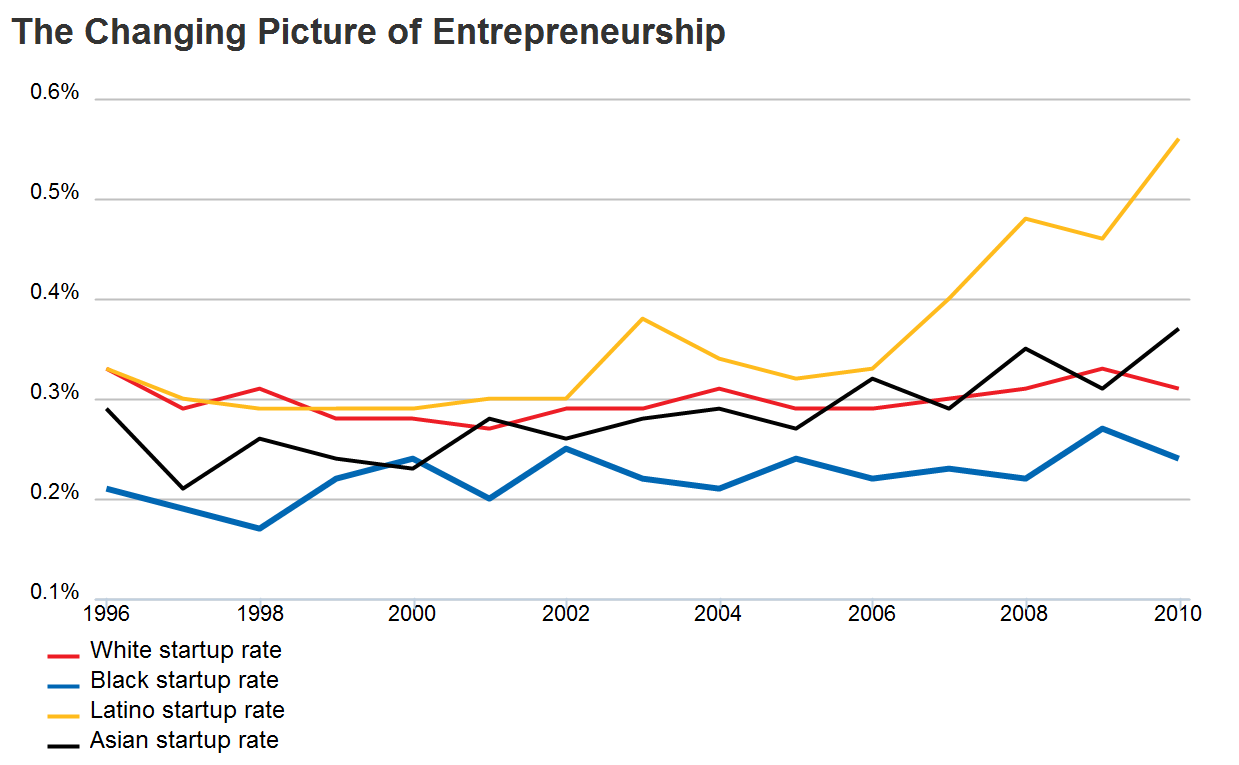

Not all news is bad concerning minority entrepreneurs. According to The Kaufman Foundation, “Latinos started businesses in 2010 at a higher rate than whites, blacks, or Asians. The entrepreneurship rate among Latinos jumped the most during the recession.” [“The Changing Picture of Entrepreneurship,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, 24 March 2011] Unfortunately, as the below chart shows (click to enlarge), blacks continue to lag behind other groups.

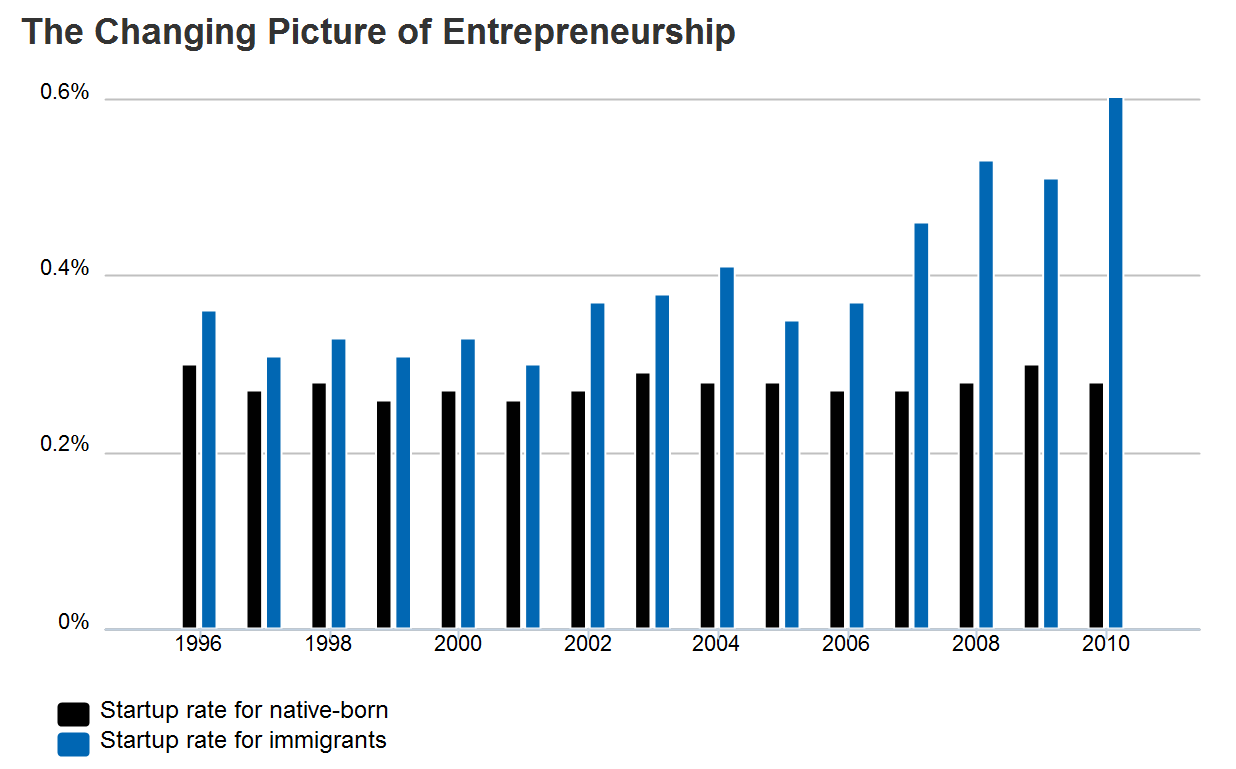

One of the reasons that Kaufman Foundation analysts offer for the jump in Latino start-ups is that the Latino community was particularly hard hit by the plunging housing market since many of them work in the construction industry. As housing starts fell, the number of Latino start-up businesses grew. When you slice the entrepreneurial pie in a different way, another fact stands out. “Business creation has increased in the recession. But one group is clearly outpacing other sectors of the population: Immigrants.” [“Immigrant Entrepreneurs Top List,” by Emily Maltby, The Wall Street Journal, 7 March 2011]. Maltby’s article is based on the same Kaufman Foundation data as the Bloomberg BusinessWeek feature. She writes:

“The study looked at start-up activity over a 15-year period, analyzing trends in the overall entrepreneurship arena and in cross-sections of the population. Several noticeable trends bubbled up from the collection of data. For example, the rate of new ventures is highest in Western and Southern states. Entrepreneurial activity has increased substantially for those lacking a high-school degree – the least-educated group in the report. And immigrants, very noticeably, are creating new business ventures at unprecedented rates. Each month last year, 0.34% of adults in the U.S. created a new business, totaling some 565,000 start-ups per month. That’s about the same as 2009’s rate, continuing the highest level of start-ups over the past 15 years. (By comparison, the highest rate before 2008 was 0.31%.) The report indicates that those born outside the U.S. are pulling a lot of that weight. The immigrant share of new entrepreneurs is 13.4% higher from 1996. While that group grew tremendously in the last two years, the native-born rate of entrepreneurship declined in the same period, thereby widening the gap. ‘The result of these contrasting trends is that immigrants were more than twice as likely to start businesses each month in 2010 than were the native-born,’ the study concluded. There’s a catch, however. Not all those businesses can stay in the U.S. because of immigration restrictions. A start-up visa bill, aimed at helping job-creating entrepreneurs secure a green card, is moving through Congress right now. But it’s a contentious issue that may not receive enough support to pass.”

The Bloomberg BusinessWeek feature included the following figure to demonstrate the point being made by Maltby.

Although women are not minorities per se, they have been in the minority when it comes to starting businesses that make it big. One woman, Nell Merlino, wants to change all that. [“Calling Female Entrepreneurs,” by Colleen DeBaise, The Wall Street Journal, 4 March 2011] DeBaise explains:

“An organization that I’ve long admired, Make Mine a Million, has changed its format this year, aiming to help 1,000 women entrepreneurs grow their microbusinesses into million-dollar enterprises. I’ve followed Make Mine a Million since its inception, and the events I’ve attended have been inspiring, informative and even a little nerve-wracking. Watching female entrepreneurs painstakingly practice their elevator pitches – and then deliver them to live audiences – can be a nail biter. … The contest is the brainchild of Nell Merlino, who helped start Take Our Daughters to Work Day, and was co-founded by her nonprofit, Count Me In, and American Express. Under the new format, a larger group of women than past years will compete for prizes, coaching and financing. … Merlino has long held that women – to some extent – deliberately hold back on growing their businesses. Many think that by keeping the business small, they’ll have more time to spend with family. But that’s a mistake, she says, as the bigger your business is, the more you can delegate to employees and step back.”

DeBaise interviewed Merlino for Bloomberg BusinessWeek back in 2008 [“Merlino Magic,” 5 December 2008]. In that interview, Merlino stated, “I want women who are growing their businesses and creating jobs to be acknowledged as one big economic stimulus package. We’re the country’s secret weapon.” Face it; we still need all the economic stimuli we can get — especially efforts that create jobs. Even though it may be difficult for minorities to start businesses, entrepreneur Luke Johnson insists “if you catch the bug it is incurable. Once someone has enjoyed the soaring highs of creating a new venture (and despite the inevitable lows), they can never revert to working for others. For them, life would be too boring.” [“The business creation bug is incurable,” Financial Times, 22 March 2011] He continues:

“Among entrepreneurs I know, the hunger to experiment and go for it cannot be satisfied except temporarily – restlessness enters the soul, a longing to seize opportunities and improve the order of things. What are the symptoms of this illness? The authorities characterize ‘risky behavior’ as negative. For entrepreneurs, taking risks is what we do for a living. The excitement of a start-up is part of the attraction. Every time you take on a loan, open a store, trial a new product, hire a member of staff –- you are taking the chance that the initiative could fail, and your business might end up bankrupt. But the desire for gain outweighs the fear of loss –- a classic feature of the syndrome. … An unwillingness to accept defeat is an absolute hallmark of the species.”

Note that nowhere in his description of what makes a good entrepreneur does Johnson ever refer to race, creed, color, gender, age, or country of origin. Those are traits that simply don’t matter (although older entrepreneurs do enjoy a better success rate — see my post entitle Boomer Entrepreneurs). He continues:

“Like a disease, entrepreneurship is infectious. The more young people are exposed to it, the more they will embrace it as a lifestyle and philosophy. In countries such as Thailand, which has a high rate of self-employment, citizens grow up with role models all around who demonstrate initiative and independence. Rebelling against the status quo is another common trait of ‘entrepreneuritis’. If all their ideas were orthodox, where would the great innovations come from? Originality, perhaps eccentricity, and a willingness to swim against the tide mark out the business-builder. Being an entrepreneur can be bad for your physical health –- long hours, plenty of stress –- but overall I don’t believe that entrepreneurs die younger than average.”

Johnson might have carried the “disease” analogy a bit too far, but knowing how difficult it is to write a column, that’s a pardonable infraction. He notes that unlike people with some real diseases, “we embrace entrepreneurs, knowing that their zest is the engine that creates jobs and wealth.” He concludes:

“Economists, who should be the great experts, have by and large wholly failed to really comprehend the nature and motivations of entrepreneurs. It is a great failing of their profession, which they should rectify with more and better research.”

Whatever your motivation, if you are inclined to start a business, don’t let stereotypes get in your way. The Wall Street Journal offers a number of good suggestions in its Small Business How-To Guide. The topics cover everything from funding to running a business. With a little surfing on the Internet you will discover other sites that can also help you get started. As I noted in a post entitled Entrepreneurship: A Calling rather than a Career, a lot of people believe that right now is a good time to consider becoming a entrepreneur.