Like most entrepreneurs, I am fascinated with the future because of all the possibilities it holds. Frankly, it’s sometimes a challenge maintaining focus on building one business because I see business opportunities almost every day and each of them excites me. Whenever an opportunity appears viable for my current business, I grab it. I suspect in that way I’m like a lot of other entrepreneurs. One man who has been both an entrepreneur and visionary since he was a young lad is Ray Kurzweil. I think I’ve mentioned him before in a post or two. His current mantra is “live long enough to live forever.” John Tierney, writing the science section of the New York Times, provides a glimpse of what Kurzweil is currently thinking about the future [“The Future Is Now? Pretty Soon, at Least,” 3 June 2008]. Tierney begins his article with a few of Kurzweil’s current predictions:

“Do you have trouble sticking to a diet? Have patience. Within 10 years, Dr. Kurzweil explained, there will be a drug that lets you eat whatever you want without gaining weight. Worried about greenhouse gas emissions? Have faith. Solar power may look terribly uneconomical at the moment, but with the exponential progress being made in nanoengineering, Dr. Kurzweil calculates that it’ll be cost-competitive with fossil fuels in just five years, and that within 20 years all our energy will come from clean sources. Are you depressed by the prospect of dying? Well, if you can hang on another 15 years, your life expectancy will keep rising every year faster than you’re aging. And then, before the century is even half over, you can be around for the Singularity, that revolutionary transition when humans and/or machines start evolving into immortal beings with ever-improving software.”

Those prognostications alone should provide enough meat to chew on over drinks with friends some evening! Normally if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is; but, Kurzweil has a pretty good record of predicting the future.

“It may sound too good to be true, but even his critics acknowledge he’s not your ordinary sci-fi fantasist. He is a futurist with a track record and enough credibility for the National Academy of Engineering to publish his sunny forecast for solar energy. He makes his predictions using what he calls the Law of Accelerating Returns, a concept he illustrated at the [2008 World Science Festival] with a history of his own inventions for the blind. In 1976, when he pioneered a device that could scan books and read them aloud, it was the size of a washing machine. Two decades ago he predicted that ‘early in the 21st century’ blind people would be able to read anything anywhere using a handheld device. In 2002 he narrowed the arrival date to 2008. On Thursday night at the festival, he pulled out a new gadget the size of a cellphone, and when he pointed it at the brochure for the science festival, it had no trouble reading the text aloud. This invention, Dr. Kurzweil said, was no harder to anticipate than some of the predictions he made in the late 1980s, like the explosive growth of the Internet in the 1990s and a computer chess champion by 1998. (He was off by a year — Deep Blue’s chess victory came in 1997.)”

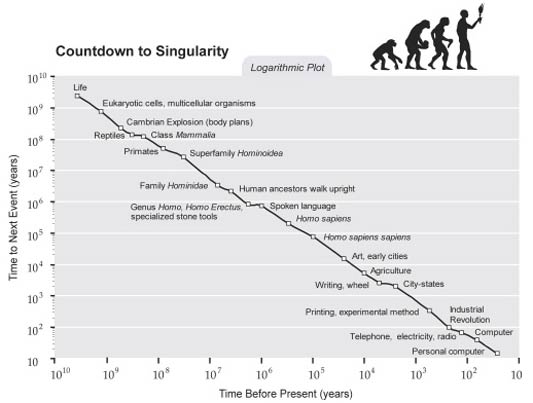

In part, Kurzweil bases his predictions of the future on the trends of the past.

“‘Certain aspects of technology follow amazingly predictable trajectories,’ he said, and showed a graph of computing power starting with the first electromechanical machines more than a century ago. At first the machines’ power doubled every three years; then in midcentury the doubling came every two years (the rate that inspired Moore’s Law); now it takes only about a year. Dr. Kurzweil has other graphs showing a century of exponential growth in the number of patents issued, the spread of telephones, the money spent on education. One graph of technological changes goes back millions of years, starting with stone tools and accelerating through the development of agriculture, writing, the Industrial Revolution and computers.”

You can find the attached image as well as a lot more of Kurzweil’s graphs at http://singularity.com/charts/page17.html. Tierney continues:

“Now, he sees biology, medicine, energy and other fields being revolutionized by information technology. His graphs already show the beginning of exponential progress in nanotechnology, in the ease of gene sequencing, in the resolution of brain scans. With these new tools, he says, by the 2020s we’ll be adding computers to our brains and building machines as smart as ourselves. This serene confidence is not shared by neuroscientists like Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, who discussed future brains with Dr. Kurzweil at the festival. It might be possible to create a thinking, empathetic machine, Dr. Ramachandran said, but it might prove too difficult to reverse-engineer the brain’s circuitry because it evolved so haphazardly.”

The Kurzweil prediction that has perhaps received the most scrutiny is what he calls the “Singularity” — a point when computers become as capable as human brains, even to the point of becoming self-aware. When that happens, and when they start working together (even melding) with the human mind, Kurzweil speculates that knowledge will advance at such a spectacular rate that virtually nothing can be predicted beyond that point. While his is both an elegant and correct use of the term, some people feel there is a Borg-like quality (for you Star Trek fans) about his singularity. The word has its roots in both mathematics and the physical sciences (specifically, cosmology). Both uses are interesting to examine. A mathematical singularity is a point at which a function no longer works in a predictable way. In cosmology, it refers to an event horizon so spectacular or powerful that no useful data is transmitted from it. The most common cosmological examples are the big bang and black holes. The common thread in these three definitions of singularity is that it is impossible to predict anything useful about them or their consequences. Tierney writes:

“Dr. Kurzweil’s predictions come under intense scrutiny in the engineering magazine IEEE Spectrum, which devotes its current issue to the Singularity. Some of the experts writing in the issue endorse Dr. Kurzweil’s belief that conscious, intelligent beings can be created, but most think it will take more than a few decades. He is accustomed to this sort of pessimism and readily acknowledges how complicated the brain is. But if experts in neurology and artificial intelligence (or solar energy or medicine) don’t buy his optimistic predictions, he says, that’s because exponential upward curves are so deceptively gradual at first. ‘Scientists imagine they’ll keep working at the present pace,’ he told me after his speech. ‘They make linear extrapolations from the past. When it took years to sequence the first 1 percent of the human genome, they worried they’d never finish, but they were right on schedule for an exponential curve. If you reach 1 percent and keep doubling your growth every year, you’ll hit 100 percent in just seven years.’ Dr. Kurzweil is so confident in these curves that he has made a $10,000 bet with Mitch Kapor, the creator of Lotus software. By 2029, Dr. Kurzweil wagers, a computer will pass the Turing Test by carrying on a conversation that is indistinguishable from a human’s.”

For those unfamiliar with the Turing Test, it comes from a 1950 paper by Alan Turing entitled “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” It is a proposed test of a computer’s ability to demonstrate intelligence. As described in Wikipedia: a human judge engages in a natural language conversation with one human and one machine, each of which try to appear human; if the judge cannot reliably tell which is which, then the machine is said to pass the test. In order to test the machine’s intelligence rather than its ability to render words into audio, the conversation is limited to a text-only channel such as a computer keyboard and screen (Turing originally suggested a teletype machine, one of the few text-only communication systems available in 1950).” Interestingly, Turing felt the question about whether machines could think was itself “too meaningless” to deserve discussion. Unfortunately, Turing didn’t live to see the emergence of the information age. He died in 1954 at the age of 41. For his part, Tierney is hedging his bets.

“I’m not as confident those graphs are going to hold up for fields besides computer science, so I’d be leery of betting on a date. But if I had to take sides in the 2029 wager, I’d put my money on Dr. Kurzweil. He could be right once again about a revolution coming sooner than expected. And I’d hate to bet against the chance to be around for this one.”

If Kurzweil’s prediction about the Singularity proves accurate, then even he will have a difficult time predicting what will happen in the second half of the twenty-first century. You can bet on this, however, it will be interesting.