David Havens (@eduhavens), an analyst at the NewSchools Venture Fund, reports, “Catalyzed by technology, education is undergoing major change.” [“Re-imaginED: The future of K12 Education,” NewSchools Venture Fund, 9 December 2013] He indicates that “95% of teachers agree that technology use in the classroom can enhance student learning” and that “80% agree that their students’ learning is more engaging when using technology.” If you have read any of my past articles on STEM education, you know that I’m a huge supporter of getting students more “engaged” in learning. I believe such engagement can best be accomplished through project-based programs that allow students to put what they have learned to work. That’s why I, along with a few colleagues, founded The Project for STEM Competitiveness — to help get a project-based, problem-solving approach into schools. Havens, however, is discussing education in general, not STEM subjects specifically. I believe, however, that whenever students are exposed to technology they are also being exposed the benefits of STEM.

In his presentation (which can be viewed in its entirety by clicking on the link above), Havens lays out compelling reasons why education needs to transform to meet today’s (and tomorrow’s) educational challenges. He notes that the percentage of low-income students is increasing, which means that their exposure to advanced technologies could be limited because of economic circumstances. At the same time, he reports that children in higher income households are improving faster than children from low-income households. This trend is bad both for the children being left behind and for America. History has demonstrated the best way for individuals and countries to escape poverty is through education. Educated people are better equipped to tackle life’s challenges. And educated people are better able to take advantage of opportunities when they are presented. Faced with growing challenges, Havens (and others) believe that technology has an important role to play in the classroom. He quotes Marion Ginapolis, Superintendent at Lake Orion Public Schools in Michigan, who stated, “It’s not about the technology; it’s about sharing knowledge and information, communicating efficiently, building learning communities and creating a culture of professionalism in schools. These are the key responsibilities of all educational leaders.”

One of the concepts discussed by Havens is “student agency,” which helps put students in charge of their lives. He references the work of Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck. As a graduate student at Yale, Dweck asked herself, “What makes a really capable child give up in the face of failure, where other children may be motivated by the failure?” [“The Effort Effect,” by Marina Krakovsky (@marinakrakovsky), Stanford Alumni Magazine, March/April 2007] Krakovsky explains what happened next:

“Dweck posited that the difference between the helpless response and its opposite — the determination to master new things and surmount challenges — lay in people’s beliefs about why they had failed. People who attributed their failures to lack of ability, Dweck thought, would become discouraged even in areas where they were capable. Those who thought they simply hadn’t tried hard enough, on the other hand, would be fueled by setbacks. This became the topic of her PhD dissertation. Dweck and her assistants ran an experiment on elementary school children whom school personnel had identified as helpless. These kids fit the definition perfectly: if they came across a few math problems they couldn’t solve, for example, they no longer could do problems they had solved before — and some didn’t recover that ability for days. Through a series of exercises, the experimenters trained half the students to chalk up their errors to insufficient effort, and encouraged them to keep going. Those children learned to persist in the face of failure — and to succeed. The control group showed no improvement at all, continuing to fall apart quickly and to recover slowly. These findings, says Dweck, ‘really supported the idea that the attributions were a key ingredient driving the helpless and mastery-oriented patterns.’ Her 1975 article on the topic has become one of the most widely cited in contemporary psychology.”

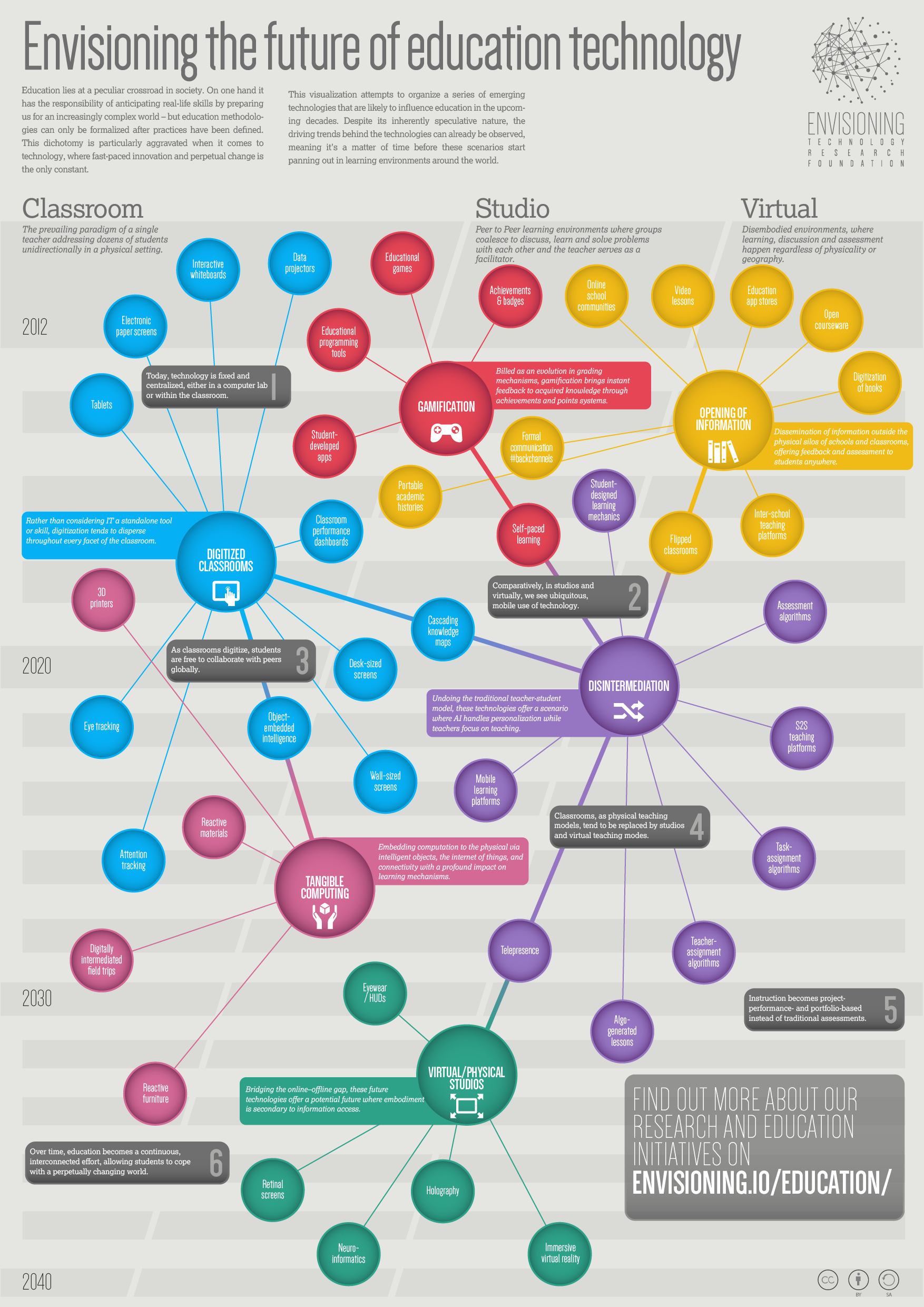

What does Dweck’s study have to do with technology in the classroom? Technology can help provide the kind of encouragement that some students need to continue to push through adversity. Personal attention is a rare commodity in many classrooms; not because teachers don’t care but because the time they can spend on each student is finite. Technology can provide undivided attention whenever it’s needed for however long it’s required. Havens notes that there are a number of educational apps that “deliver rich, diverse content” to students and that most students, even those from low-income households, have access to smartphone technology. But, he argues, there is also a need for technology in the classroom. He cites David Warlick (@dwarlick), an educator with four decades of experience, who stated, “We need technology in every classroom and in every student’s and teacher’s hand, because it is the pen and paper of our time, and it is the lens through which we experience much of our world.” The following infographic from the Envisioning Technology Research Foundation demonstrates how technologies can combine to transform education.

Anya Kamenetz (@anya1anya) asserts some technologies are more effective than others in helping students learn. [“Technology for education vs. technology for learners,” Digital/Edu, 6 May 2013] Kamenetz cites the work of two education researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Rich Halverson (@aporiatwo) and Benjamin Shapiro. Halverson and Shapiro label the best technologies “‘technologies for learners’ – as opposed to ‘technologies for education.'” Kamenetz explains:

“’Technologies for education assume that the goals (or outcomes) of teaching and learning are stable, and that the challenge of technological innovation is to fashion efficient, viable, and successful means to reach these goals,’ they write. This is a process-based model of innovation, where the goal is to make widgets faster, cheaper, and higher-quality. Examples of technologies for education would include adaptive learning software, computerized assessments, and student information and data management systems. ‘Technologies for learners, on the other hand, are designed to support the needs, goals, and styles of individuals.’ … This is what the DML Research Hub calls ‘connected learning,’ and it mostly happens out of school.”

Like Kamenetz, Halverson, and Shapiro, I believe we need to get more connected learning into schools. Kamenetz points out, however, that getting more connected learning into schools won’t be easy. She asserts that both the rhetoric and the mindset of today’s educators “compels the spread of technologies for education” rather than technologies for learning. Halverson and Shapiro note that “the benefits of self-directed, creative, and project-based learning don’t necessarily show up on standardized test scores,” which is why “accountability pushes schools away from technologies for learners.” That’s a shame because the most beneficial knowledge and skills that students can learn are those that they can apply to life’s challenges.