This is the third post in a 4-part series on globalization’s flows. As I noted in the first post in the series, those flows traditionally include resources, capital, and people. More recently information and ideas have been added by many analysts. In order for the global economy to grow, these assets must be relatively free to move around the globe (either physically or virtually). When one talks about the flow of capital these days, three topics are often the focus: first, foreign direct investments (FDI) (the traditional benchmark for how well a developing country is doing); second, currency flows (more specifically, heated speculation in high-risk currencies); and, finally, sovereign debt (e.g., much of America’s debt is owed to other countries, like China and Japan). I’ll discuss each of these flows in turn beginning with FDI.

Foreign Direct Investment

Jeffrey P. Graham and R. Barry Spaulding explain why foreign direct investment has had such a profound effect on economic growth in developing countries [“Understanding Foreign Direct Investment (FDI),” Going Global, 18 June 2005]. They write:

“Foreign direct investment (FDI) plays an extraordinary and growing role in global business. It can provide a firm with new markets and marketing channels, cheaper production facilities, access to new technology, products, skills and financing. For a host country or the foreign firm which receives the investment, it can provide a source of new technologies, capital, processes, products, organizational technologies and management skills, and as such can provide a strong impetus to economic development. Foreign direct investment, in its classic definition, is defined as a company from one country making a physical investment into building a factory in another country. The direct investment in buildings, machinery and equipment is in contrast with making a portfolio investment, which is considered an indirect investment. In recent years, given rapid growth and change in global investment patterns, the definition has been broadened to include the acquisition of a lasting management interest in a company or enterprise outside the investing firm’s home country. As such, it may take many forms, such as a direct acquisition of a foreign firm, construction of a facility, or investment in a joint venture or strategic alliance with a local firm with attendant input of technology, licensing of intellectual property. In the past decade, FDI has come to play a major role in the internationalization of business.”

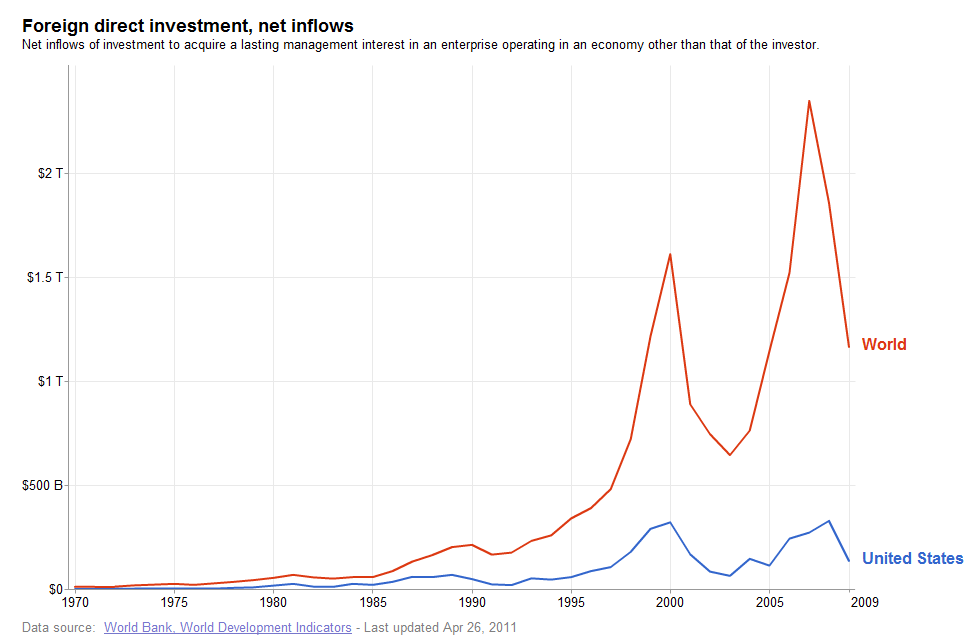

As one can see from the following graphic (click to enlarge), FDI declined significantly during the Great Recession; but most analysts expect FDI to start increasing again this year.

To see how FDI flows have changed over the years, review the UNCTAD Stat spreadsheet on Inward and outward foreign direct investment flows, annual, 1970-2009. The spreadsheet parses FDI geographically as well as in a number of other useful ways.

Currency Flows

At a recent conference involving the so-called BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), leaders from these countries issued a statement that included the following: “We call for more attention to the risks of massive cross-border capital flows now faced by the emerging economies.” [“Brics Group Warns on Capital Flows,” by Alexander Kolyander and Owen Fletcher, The Wall Street Journal, 15 April 2011] The concern is that currency speculation can trigger inflation and foster currency volatility. Either of those outcomes hurts economic growth and can have a devastating effect on those trying to claw their way out of poverty. Kolyander and Fletcher continue:

“Brics officials have warned that developing countries face risks from capital inflows caused by loose monetary policies of developed nations. Trade officials from the five nations on Wednesday said they still face economic overheating issues, and agreed they need to boost coordination in the Group of 20 nations and other forums to ensure the interests of developing countries, according to Chinese Commerce Minister Chen Deming.”

Analysts at UBS predict, “Volatility in currency markets is likely to continue, driven by concerns about European sovereign debt and developments in the Middle East and Japan.” [“UBS profits and net new inflows up,” by Ellen Wallace, Genevalunch.com, 26 April 2011] Currency volatility is one reason that gold and silver prices have skyrocketed. What does the future hold? Your guess is probably as good as the experts according to Neil Shah [“Currency Investors: What, Me Worry?” The Wall Street Journal, 13 April 2011]. He writes:

“Optimists say the foreign-exchange markets are simply returning to normal after gyrating during the global recession. Among the comforting signals: Economies are picking up steam; international trade—a huge driver of foreign-exchange flows—is rebounding; prices are soaring for U.S. stocks and other risky investments like ‘junk’ bonds; Spain, the euro-zone’s fourth-biggest economy, has avoided infection from Europe’s financial crisis; and investors and corporate executives are sitting on trillions of dollars of unused cash. But skeptics warn that, with crises erupting around the globe, investors are choosing to chase gains rather than risk picking the wrong danger to hedge against. ‘I just don’t see how volatility will not increase quite substantially,’ says George Papamarkakis of London-based hedge fund North Asset Management LLP, which manages about $200 million. Some fear that currency prices have been distorted by global monetary authorities, who have flooded the financial markets with cheap cash to coax the global economy back to life. When central bankers move to drain away this cash, the market’s tide could roll back, leaving some investors exposed to souring bets.”

In the age of exchange traded funds (ETF), my suspicion is that currency speculation will continue to foster volatility.

Sovereign Debt

Since the end of the Second World War, the U.S. dollar has been the global reserve currency of choice. It is the standard against which most other currencies are judged. With U.S. sovereign debt spiraling upwards and no clear debt reduction plan in place, countries around the globe (but especially the BRICS) are expressing their “desire to shift away from reliance on the U.S. dollar.” [Kolyander and Fletcher, op. cit.] Kolyander and Fletcher report:

“Brics nations support revisions to the global monetary system leading to ‘a broad-based international reserve currency system providing stability and certainty’—a reference to their desire for a diminished role for the dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency. As part of the effort to reduce reliance on the dollar, the state development banks of the five countries agreed to open credit lines in their national currencies to each other. … The Brics leaders said they welcome current discussions about elevating the role of special drawing rights, a synthetic reserve currency created by the International Monetary Fund, and discussions on changing its composition. The Brics statement didn’t specifically refer to discussions about including the Chinese yuan in the basket of currencies that makes up the SDR—a dicey issue because it could require China to drastically loosen its controls over its currency.”

China demonstrated its concern about the U.S. fiscal environment by reducing “its net holdings of U.S. Treasurys.” [“China Sells US Treasurys For 4th Straight Month,” by Jeff Bater and Andrew Ackerman, The Wall Street Journal, 15 April 2011] That said, China remains the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasurys. Bater and Ackerman report that “foreigners [remain] net buyers of long-term U.S. financial assets” but global demand for U.S. Treasurys is slowing “amid heated debate within the U.S. over how to reduce its high budget deficits, which it must finance by selling securities at home and abroad.”

Of course, the U.S. is not alone in facing a sovereign debt crisis. Some European countries are facing even more severe crises. In February 2010, Niall Ferguson wrote, “It began in Athens. It is spreading to Lisbon and Madrid. But it would be a grave mistake to assume that the sovereign debt crisis that is unfolding will remain confined to the weaker eurozone economies. … It is a fiscal crisis of the western world. Its ramifications are far more profound than most investors currently appreciate.” [“A Greek crisis is coming to America,” Financial Times, 10 February 2010]. Surely investors now fully appreciate the consequences of sovereign debt.

Conclusions

So what does this all mean? Certainly the picture is mixed. Countries are starting to make tough decisions about sovereign debt, but they are making them even as the world is trying to emerge from a significant financial crisis. If the global economy continues to recover, then government actions to reduce deficits are a good thing. Growth market countries, like China, India, and Brazil, are focused on cooling down their economies so that they can keep inflation in check. That is why they are concerned about currency volatility that could derail their plans. The good news is that they don’t plan on being blindsided and are taking positive actions. On the whole, I believe that countries around the world are becoming much more attuned and attentive to fiscal policies. Whether the world finds a reserve currency (or system) to replace the U.S. dollar is problematic. My guess is that the best candidate for replacing the dollar is Special Drawing Rights because “some economists argue that SDRs could be used as a less volatile alternative to the U.S. dollar.” [“IMF calls for dollar alternative,” by Ben Rooney, CNNMoney, 10 February 2011]. Even if SDR replaces the dollar as an international standard, I suspect that most commodities will still be quoted in dollars since most people wouldn’t understand how to interpret the price of oil or a bushel of corn in SDRs.