Just before the Christmas holiday, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) announced a new hours-of-service (HOS) rule that “reduces by 12 hours the maximum number of hours a truck driver can work within a week. Under the old rule, truck drivers could work on average up to 82 hours within a seven-day period. The new HOS final rule limits a driver’s work week to 70 hours.” [“U.S. Department of Transportation Takes Action to Ensure Truck Driver Rest Time and Improve Safety Behind the Wheel,” FMCSA Press Release 37-11, 22 December 2011] According to the press release, “commercial truck drivers and companies must comply with the HOS final rule by July 1, 2013.” The FMCSA asserted that it established the new HOS rule based on “the latest research in driver fatigue.” The new rule will “make sure truck drivers can get the rest they need to operate safely when on the road.”

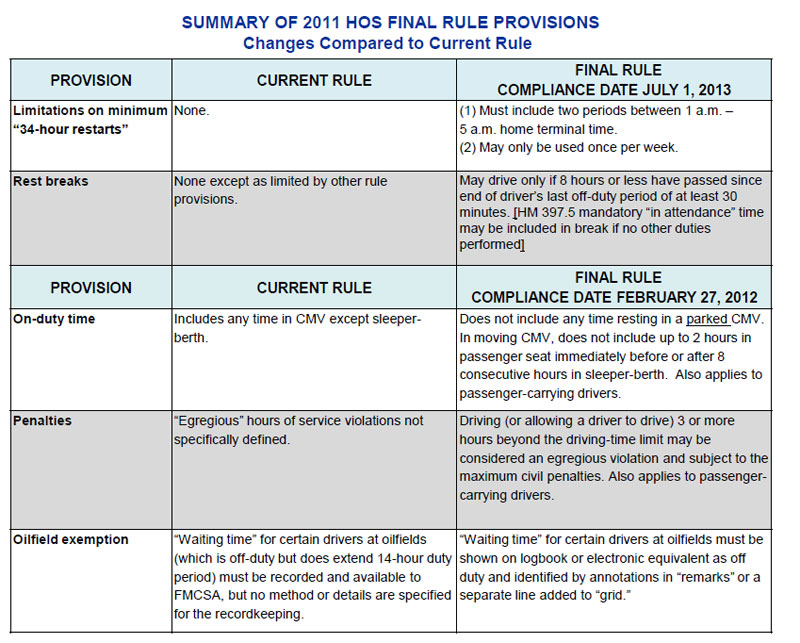

Although the new rule shortens the hours a trucker can work in a week, “the final rule retains the current 11-hour daily driving limit.” Many truckers and trucking firms were afraid that the daily limit would be shortened to 10 hours. The FMCSA summarized rule changes in the following chart:

As one might expect, most truckers aren’t happy with the new rules because fewer hours mean less money in their pocket. “The Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association (OOIDA) said the new rules represented a ‘one-size-fits-all approach’ that will do nothing to improve highway safety.” [“New Hours of Service Rules Finally Announced,” Supply Chain Digest, 22 December 2011] Todd Spencer, executive OOIDA vice-president, told the SCD staff, “Collectively, the changes in this rule will have a dramatic effect on the lives and livelihoods of small-business truckers. The changes are unnecessary and unwelcome and will result in no significant safety gains.” The article reports that “OOIDA was hoping any changes would involve more flexibility for truckers.” The article continues:

“‘Compliance with any regulation is already a challenge because everyone else in the supply chain is free to waste the driver’s time loading or unloading with no accountability,’ said Spencer. ‘The hours-of-service regulations should instead be more flexible to allow drivers to sleep when tired and to work when rested and not penalize them for doing so. It’s the only way to reach significant gains in highway safety and reduce non-compliance.’ The American Trucking Associations was also not happy with the changes. … ‘What is surprising and new to us is that for the first time in the agency’s history, FMCSA has chosen to eschew a stream of positive safety data and cave in to a vocal anti-truck minority and issue a rule that will have no positive impact on safety,’ ATA president and CEO Bill Graves said.”

The strongest argument against the new HOS rule is the one presented by Spencer that notes that “everyone else in the supply chain is free to waste the driver’s time loading or unloading with no accountability.” Some flexibility should probably have been built into the rules to account for such off-road activities. The article continues:

“‘By forcing through these changes FMCSA has created a situation that will ultimately please no one, with the likely exception of organized labor,’ added Dan England, ATA chair and chair of C.R. England. ‘Both the trucking industry and consumers will suffer the impact of reduced productivity and higher costs. Also, groups that have historically been critical of the current hours of service rules won’t be happy since they will have once again failed to obtain an unjustified reduction in allowable daily driving time. Further, it is entirely possible that these changes may actually increase truck-involved crashes by forcing trucks to have more interaction with passenger vehicles and increasing the risk to all drivers.”

Graves told the SCD staff that “it is possible the ATA will challenge the rules in court.” Dustin Mattison engaged in a broader discussion of the trucking industry in an interview with John Morris, head of Cushman & Wakefield’s global consulting group. [“The Future of Trucking in 2012 and Beyond ,” Dustin Mattison’s Blog, 13 December 2011] Mattison’s first question for Morris was, “I have heard some concerns in the trucking industry about the future, what is the issue here?”

“Obviously, the biggest concern here is the economy. If you believe that the economy is recovering or will recover in the near future, this means more goods and services will ship via truck. 75-80% of the goods shipped in this country do ship via truck as compared to planes and trains. At some the demand for those services will rise, perhaps even significantly. In the trucking industry today it is really an industry in disarray. It has always been a low margin industry. The inflation rate on trucking pricing, or what a carrier can charge for a load since 2000 has been zero. Surviving in an industry where prices haven’t gone up in 11 years is not easy. Because of this as well as 3 years of a recession it is an industry where rates remain depressed, margins remain zero or negative in many cases. What is happening now is that the equipment and people shortages that the industry is facing are leaving some risk for all of us who shop and buy. It may at some point in the future take a lot more money to get those items to our stores.”

Morris’ belief that the trucking industry is facing “equipment and people shortages” seems to be widely accepted. Most often these shortages are talked about in terms of a shrinking capacity. The staff at American Shipper reports, “The commercial truck scarcity predicted for the past two years is starting to become reality, forcing shippers to rethink how to keep their supply networks functioning smoothly. U.S. truck capacity is so tight that analysts and trucking executives are warning of serious shortages at the slightest sign of improvement in the economy.” [“Where did all the trucks go?,” 24 October 2011] Mattison’s next question for Morris was, “What are the major variables involved?”

“Overall, the trucking industry since the heyday back during an economic boom in 2006 has lost about 20-25% of its capacity. This has been due to the fact that freight tonnage, or things shipped since 2006 has dropped 30%. … The first major variable would be equipment. When all of that equipment went dormant much of it was sold and much was scrapped. Many of the carriers in business went out of business. … The second major variable is drivers. Driving a truck for some people is not an appealing career. Much of the generation coming into the workforce would not consider it to be a job option. Because of this, in the middle of the last decade the industry was already short about 200,000 drivers to meet demand. That figure is a little lower at about 125,000 today, according to the American Trucking Association[s] (ATA). However, it is expected to balloon, if and when economic recovery is sustained, to as many as 400,000 drivers. If we are in a market that has 30% less capacity and 400,000 fewer drivers than needed you would expect a lack of stability in pricing and service. John thinks the other major variable is regulation. There have been significant carbon and engine regulations over the last few years. This means that much of this equipment that is dormant or retired and dormant is no longer eligible to travel. … There are also other kinds of compliance and Safety & Accountability Initiatives, such as Hours and Service, state reporting of crashing, greater carrier scrutiny, and certainly as you would expect and hope higher standards for drug and alcohol testing.”

Morris sees all these variables combining into a perfect storm that will have a significant impact on service and price in the trucking industry. Mattison, therefore, asked him, “What do you see happening as a result of this?”

“One could expect that over the road costs could at some point over the next 24 months reach over $2.25 per mile, with significant price increases. There was a period last year when the recession was in principle over. People were returning to shipping. Inventories had been replenished. There was one of the sharpest rises in truckload pricing over a 3 month period which the industry had never seen. John and his team talk to clients now who tell them that in some parts of the country they can’t get equipment. The carriers they are working with have little or no capacity to offer. It is making them seriously consider where they are and who they are using. This points to regional networks and national networks. John thinks there are impacts to the overall cost of transportation and what we all pay for goods. As the economy returns to some level of normal GDP growth everyone believes there is a risk of inflation. This along with fuel and gasoline is one of the major risk factors involved in contributing to what could be significant rates of inflation over the next 18-36 months.”

With limited capacity being a known and significant challenge, companies may be tempted to build private fleets, but Andy Moses, senior vice president of global products for Penske Logistics, recommends considering a dedicated fleet. [“Private vs. Dedicated Fleet? Top Shipper Considerations,” Move Ahead, 17 November 2011] He writes:

“The combined forces of rising energy, equipment and commodity prices have created a strain on transportation budgets. Simply put, the costs of acquiring, fueling and operating a fleet continues to rise. Logistics managers face competing pressures to reduce internal costs, without sacrificing service levels required by value-conscious customers. Not surprisingly, in-house fleets are under significant pressure to justify their effectiveness vs. available alternatives. Options generally include the increased use of common carriers or conversion from a private fleet to a dedicated contract carriage arrangement with a logistics provider. Shippers in service sensitive applications tend to view private and dedicated fleets as the most practical options to deliver the operational performance required to be competitive in their particular industry.”

His conclusion is: “Well-run private fleets, and properly structured and monitored dedicated fleets, represent two good options for shippers in service sensitive businesses. In some cases, a combination of the approaches makes the most sense based on the dynamics of a given shipper’s distribution needs.” The challenge, of course, even using these options, will be finding enough drivers and available equipment to meet demand. With so much of America’s supply chain reliant on the trucking industry, it will be a critical sector to watch.