Unless you are part the food supply chain, you might not be aware that last July China ceased exporting fertilizer to the rest of world. And, following Russia’s unprovoked attack against Ukraine in February 2022, which spurred international sanctions, Russia, in retaliation, also halted fertilizer exports. What does this mean for the food supply chain? Bloomberg reports, “For the first time ever, farmers the world over — all at the same time — are testing the limits of how little chemical fertilizer they can apply without devastating their yields come harvest time. Early predictions are bleak.”[1] How bleak? Bloomberg reports some crop yields could drop by as much as 15 percent.

Agriculture experts Charlotte Hebebrand, Executive Vice President for Stakeholder Relations and Chief Sustainability Officer at Nutrien, and David Laborde, a Senior Research Fellow with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), observe, “Like people, plants need a multitude of nutrients to thrive. These are categorized into micronutrients, such as zinc and iron; secondary macronutrients; such as calcium and magnesium; and three primary macronutrients: nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Mineral fertilizers provide higher and more plant accessible nutrients, while organic minerals importantly also provide carbon, which contributes to healthy soils. While efforts to reduce nutrient losses to the environment must be continued and stepped up, it bears emphasizing that fertilizers play a crucial role in agricultural productivity.”[2]

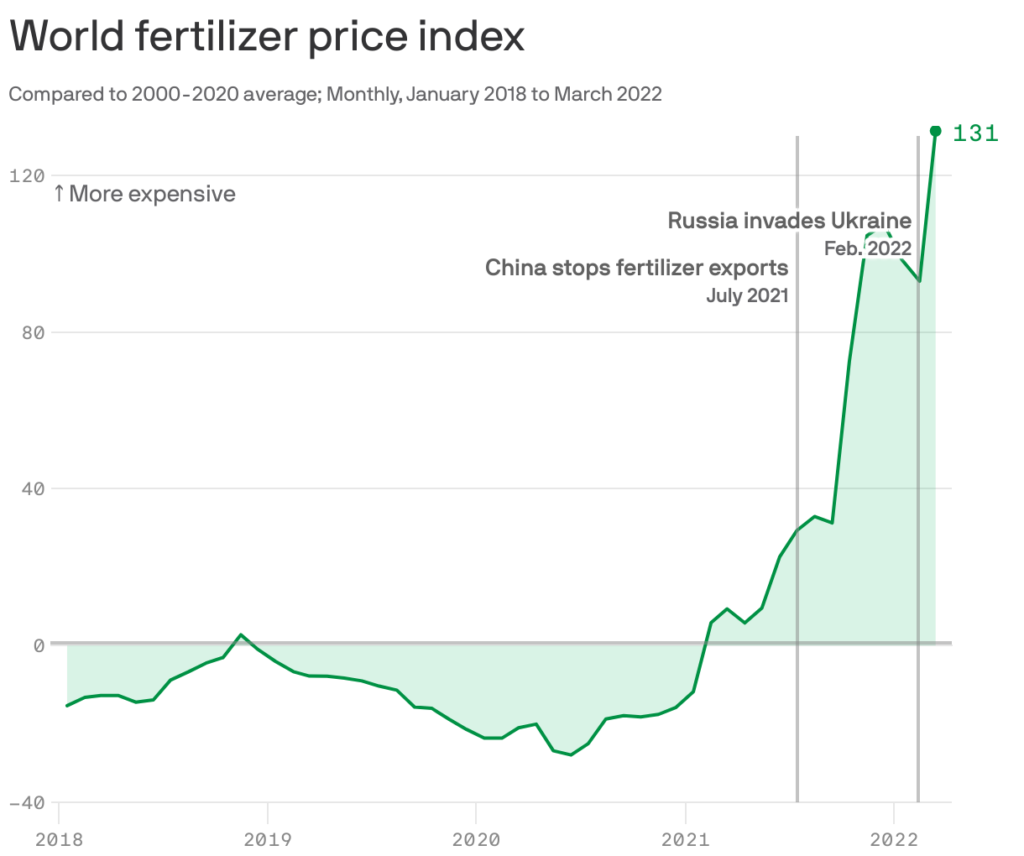

Rising Fertilizer Prices

Hebebrand and Laborde report, “World market prices for both food and fertilizer (here we focus only on N, P and K) increased significantly over the past year and a half and have climbed to even higher levels following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, hitting their highest levels yet in March.” Using IFPRI data, Axios Visuals prepared the following graphic demonstrating the steep rise in the world fertilizer price index.

Hebebrand and Laborde explain, “Fertilizer price spikes and concerns about availability cast a shadow on future harvests, and thus risk keeping food prices high for a longer period.” But high food prices aren’t the only concern. Feeding a growing global population is also a concern — and fertilizers can make a big difference in crop yields. Bloomberg reporters explain, “Commercial farmers rely on a combination of three key nutrients — nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium — to fuel their harvests. Those inputs have always been key, but it was only about a century ago that humanity learned to manufacture mass-produced ammonia-based nutrients. The discovery of the Haber-Bosch method in the early 1900s, which is still used to make fertilizer today, has allowed farmers to vastly increase their yields. The agriculture industry has since come to depend on — even hinge on — man-made fertilizer. Although soil’s needs are different region to region, the general trend is pretty undisputed: More fertilizer use brings more food production.” The opposite is also true: Less fertilizer use means less food production.

Consequences for the Food Supply Chain

Bloomberg reporters paint the consequences of the current fertilizer shortage in the starkest of terms. They write:

“For the billions of people around the world who don’t work in agriculture, the global shortage of affordable fertilizer likely reads like a distant problem. In truth, it will leave no household unscathed. In even the least-disruptive scenario, soaring prices for synthetic nutrients will result in lower crop yields and higher grocery-store prices for everything from milk to beef to packaged foods for months or even years to come across the developed world. And in developing economies already facing high levels of food insecurity? Lower fertilizer use risks engendering malnutrition, political unrest and, ultimately, the otherwise avoidable loss of human life.”

Hebebrand and Laborde agree with that assessment. They write, “These problems will spread in the coming months; ultimately all farmers around the world will be impacted. The price shock may be buffered for farmers in some emerging and developing countries that have fertilizer subsidy regimes in place (e.g., India, China, Bangladesh, and Ghana) but those regimes are going to place tremendous fiscal pressure on budgets already stressed by substantial government outlays during the COVID-19 epidemic.” They are very concerned, however, about the African continent. They explain, “Relatively smaller markets — especially many African countries — face a particularly difficult situation, as producers and traders are likely to favor shipping limited supplies to larger markets. Given Africa’s still-limited use fertilizers — an estimated average of 25 kg per hectare, a fraction of the global average, 121 kg/ha — a decline in fertilizer use would lead to significantly reduced productivity for the continent, with potentially serious consequences for food security.”

You’ve heard the term “every cloud has a silver lining.” Farmers selling manure are seeing that silver lining. Journalists P.J. Huffstutter (@pjhuffstutter), Tom Polansek (@tpolansek), and Bianca Flowers (@biancashamell) report, “For nearly two decades, Abe Sandquist has used every marketing tool he can think of to sell the back end of a cow. Poop, after all, needs to go somewhere. The Midwestern entrepreneur has worked hard to woo farmers on its benefits for their crops. Now, facing a global shortage of commercial fertilizers made worse by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, more U.S. growers are knocking on his door. Sandquist says they’re clamoring to get their hands on something Old MacDonald would swear by: old-fashioned animal manure.”[4] They add, “Not only are more U.S. farmers hunting manure supplies for this spring planting season, some cattle feeders that sell waste are sold out through the end of the year.”

Facundo Calvo (@facundo_calvo_), a Policy Analyst specialized in Trade and Agriculture at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), sees the current crisis as an opportunity for the world to explore changing the way it fertilizes crops. He writes, “The Russia-Ukraine war has put front and center our long-standing reliance on natural gas, which is problematic from a climate change perspective and forces us to reconsider how fertilizers are produced.”[4] He reports, “There are promising scientific developments underway for alternative fertilizers, but many of these approaches need further development. For example, scientists are working to perfect a process known as ‘biological nitrogen fixation,’ where legumes such as peas, beans, or lentils, by using a particular type of soil bacteria called rhizobia, ‘reduce’ or ‘fix’ nitrogen from the atmosphere into a form that crops can use as a fertilizer. If further developed, scientific experts say this could be a viable alternative to nitrogen fertilizers that rely on natural gas. However, research and development on fertilizers based on biological nitrogen fixation are still at a very early stage. Beyond a subset of legumes, more research is needed to understand how transformed cereals crops such as rice, wheat, or corn can form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria to get the nitrogen they need.”

Another promising advancement has been made by an international team of scientists led by Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. They have developed a greener alternative to the Haber-Bosch method for manufacturing fertilizer ingredients. The university reports, “The method produces a compound known as ‘urea’, which is a natural product found in the urine of mammals, and an essential compound for fertilizers that is mass-produced industrially to increase crop yields. … The team found a way to greatly improve an existing alternative approach to urea production known as electrocatalysis — using electricity to drive chemical reactions in a solution. … This new method to produce urea may inspire the future design of sustainable chemistry approaches and contribute to ‘greener’ agricultural practices to feed the world’s growing population, say the research team.”[5] The research team also notes, “The new method is simple enough to be adopted at both large and small scales. The electrocatalytic device could be easily operated by farmers to generate their own urea for fertilizers. The method could also one day be powered entirely by renewable energy.”

In another promising development, Hannah Ritchie (@_HannahRitchie), Head of Research at Our World In Data, reports, a decade-long experiment in China achieved an average increase of around 11% in the yields of maize, rice and wheat while decreasing the use of nitrogen fertilizer by around 16%.[6] She adds, “This wasn’t achieved through major technological innovations or policy changes: it involved educating and training farmers on good management practices.”

Concluding Thoughts

Hebebrand and Laborde conclude, “While risks around fertilizer availability and affordability will vary by country and region, farmers in many low-income countries face potential hardship as the Ukraine crisis continues. If these challenges are not addressed, harvests will suffer, keeping pressure on food prices beyond the short run and adding to food security concerns in many developing countries.” Addressing those challenges, won’t be easy. Nevertheless, the current crisis may spur innovative research into alternate fertilizing methods. There is no silver bullet solution to the fertilizer shortage crisis. All promising avenues should be explored.

Footnotes

[1] Bloomberg, “Can the World Feed Itself? Historic Fertilizer Crunch Threatens Food Security,” SupplyChainBrain, 5 may 2022.

[2] Charlotte Hebebrand and David Laborde, “High fertilizer prices contribute to rising global food security concerns,”

[3] P.J. Huffstutter, Tom Polansek, and Bianca Flowers, “No poop for you: Manure supplies run short as fertilizer prices soar,” Reuters, 6 April 2022.

[4] Facundo Calvo, “Tackling Hunger and Global Food Insecurity: Why we must leave nitrogen fertilizers behind,” International Institute for Sustainable Development, 24 March 2022.

[5] Nanyang Technological University, “Scientists develop ‘greener’ way to make fertilizer,” Science Daily, 19 August 2021.

[6] Hannah Ritchie, “Can we reduce fertilizer use without sacrificing food production?” Our World In Data, 9 September 2021.