SCE Magazine reports “that company executives are coming under increasing pressure from customers, shareholders and regulators, to better address the issue of supply chain risk.” [“Just How Resilient Is Your Supply Chain?” SupplyChainBrain, 3 September 2013] This increasing pressure is undoubtedly the result of a string of major supply chain disruptions that has plagued global supply chains over the past decade. These disruptions have been caused by unexpected natural disasters (e.g., volcanoes and tsunamis) as well as man-made disasters (e.g., conflict and industrial accidents). The article notes that because “many businesses operate a ‘just in time’ production strategy to keep inventories low and the production of key components and other services is outsourced to reduce costs” even the slightest disruption can have significant perturbative effects. The article concludes:

“To reduce the risks, companies need to make resilience of their supply chains a top priority. They need to ensure that they and their suppliers have business continuity plans that are capable of responding to any number of potential crisis scenarios. Executives should be aware that it is not just their own supply chain that is at risk, but any weakness in a supplier’s supply chain is also a problem. A common issue that companies often overlook is the risk beyond their immediate suppliers – to their suppliers’ suppliers – and don’t regularly assess the resilience of the risk mitigation standards of even their most critical suppliers.”

Noted supply chain analyst Lora Cecere has been making this point for years. Even though supply chain risk management is rising on corporate priority lists, a recent study concluded that “only 41% of companies surveyed are considered to have ‘mature’ supply chain risk management processes.” [“Majority of firms lack ‘mature’ supply chain risk management: survey,” Canadian Underwriter, 13 August 2013] The article goes on to report that even though companies don’t have mature SCRM processes, “nearly four in five mitigate against disruptions by implementing a dual sourcing strategy.” If, however, the both sources are in the same general location, this strategy is only effective against man-made disruptions from a single supplier.

The report, entitled 2013 Global Supply Chain and Risk Management Strategy, was released by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)’s Forum for Supply Chain Innovation and was written in collaboration with the audit and consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. The report concludes:

“Our research validated that companies with mature risk processes perform operationally and financially better. Indeed, managing supply chain risk is good for all parts of the business – product design, development, operations and sales.”

According to the article, respondents who participated in the study looked on potential risks with a fairly broad perspective:

“About half (53%) said raw material price fluctuations were sources of risk, 47% identified currency fluctuations, 34% identified environmental catastrophes, 28% identified raw material scarcity, 22% identified geopolitical instability, 22% identified supplier partner bankruptcy, 20% identified change in technology, 12% cited unplanned IT interruptions and 5% identified telecommunications outages while only 2% identified cyber attacks as sources of risk to their supply chains.”

I’ll explain in a future post why downplaying cyber risks could prove dangerous. Glen B. Alleman reminds us that “there are many definitions of risk from a variety of sources.” [“More Uncertainty and Risk,” Herding Cats, 5 May 2013] “In the end,” he writes, “these definitions are all pretty much the same.” The elements of most definitions, he points out, include:

- “Risk involves the probability of something happening in the future.

- “When that something happens it impacts the project in ways that are not good.

- “There can be a probability of the effect of the impact as well.

- “Handling the risk means knowing what kind of risk it is, and what the choices are for handling the risk.”

He offers the following redacted definition of risk that he believes “can be used in probably any domain.”

“Risk refers to the uncertainty that surrounds future events and outcomes. It is the expression of the likelihood (probability of occurrence) and (probability of) impact of an event with the potential to influence the achievement of an organization’s objectives.” – Managing Risk in Government: An Introduction to Enterprise Risk Management, IBM Center for The Business of Government.

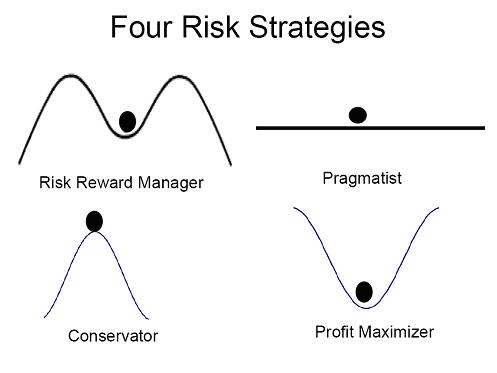

Supply chain analyst Bob Ferrari asserts, “Every supply chain management team needs to have … vibrant supply chain risk mitigation and management plans in-place. Evidence continues to point to yet more profound reminders to the ongoing existence of supply chain risk.” [“Yet More Evidence to the Ongoing Existence of Industry Supply Chain Risk,” Supply Chain Matters, 19 August 2013] The question often arises about how much risk a company is willing to take. This is sometimes referred to as Risk Appetite. A blog entitled Riskviews lays out four strategies that can help a company determine whether it is suited to determine its Risk Appetite (see the image below).

The article explains these strategies this way:

“If your risk attitude is what we call MAXIMIZER, then you will believe that you should be able to accept as much adequately priced risk as you can find. If your risk attitude is what we call CONSERVATOR, then you will believe that you should mostly accept only risks that … you are comfortable with. … If your risk attitude is what we call PRAGMATIST, then you will believe that it is a waste of time to set down a rule like that in advance. How would you know what the opportunities will be in the future? … You would think that it is a waste of time to worry about such an unknowable issue. Only the companies that are driven by what we call the MANAGERS would embrace the risk appetite idea. … The risk managers should also be able to help the top management of the company to select the corporate strategic balance, reflecting the best combination of risks to optimize the risk reward balance of the company.”

David M. Katz believes that Risk Appetite should always be partnered with another metric called risk-bearing capacity (RBC). [“How Much Risk Can Your Company Bear?” CFO, 23 April 2013] Katz insists that using RBC is necessary for companies “to gauge their appetite for risky, financially threatening activities.” Katz indicates that he finds it puzzling that some “CFOs may be trying to judge risk appetite without the benefit of valuable quantitative metrics, like RBC.” He continues:

“RBC is a prospective view of risk that is useful in establishing allocations of risk, capital or both to drive value for the shareholders and the organization as a whole. … While RBC is calculated in different ways depending on the key performance indicators of a given company or industry, the common basis for the calculation is ‘how much risk the organization can bear before [it becomes] insolvent,’ said Carol Fox, the director of the strategic and enterprise risk practice at [Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS)].”

Katz points to a survey published by RIMS that concludes, “Given the widespread disconnect between senior management and risk pros, [companies] may have a long way to go.” Douglas Macdonald, Procurement Portfolio Product Marketing Leader at IBM, indicates that best-in-class companies all share several characteristics when it comes to dealing with risk management. [“Develop risk management through an adaptable supply chain,” SupplyChain Digital, 15 April 2013] They are:

“Risk Identification: Best-in-class procurement organizations use technology and information services as a starting point to identify sources of risk. Examples include:

• Identifying components sourced from either suppliers that are at financial risk or are concentrated in a specific geographic region more vulnerable to political conflicts or currency fluctuations.

• Identifying components of production that are either sole sourced or come from very specialized suppliers, thus increasing the company’s dependence on them.

“Risk Prioritization: Best-in-class procurement organizations perform ‘what if’ analysis and quantify the impact of supply risk for specific components and commodities. Armed with such analysis, they prioritize actions on those components and commodities that have the greatest potential impact on the business.

“Risk Mitigation: Best-in-class procurement organizations also go beyond mere risk identification, to actively manage and mitigate supply base risks.”

I agree with Macdonald that the companies that will flourish in the decades ahead are those who implement adaptable supply chains that proactively manage and mitigate supply chain risks. Regardless of how careful a company is or how good of a risk management process it maintains, it is going to still face risks that are out of its control. How much risk it is willing to bear is something that that each company should carefully consider.