Terms like “100-year” or “1000-year” events no longer seem applicable or appropriate in the face of rapidly changing climate conditions. The U.S. Geological Survey notes, “The term ‘100-year flood’ is used in an attempt to simplify the definition of a flood that statistically has a 1-percent chance of occurring in any given year. Likewise, the term ‘100-year storm’ is used to define a rainfall event that statistically has this same 1-percent chance of occurring.”[1] The excessive rain that caused devastating flooding in South Carolina in October 2015 was labeled a “1000-year rain event” with some locations receiving up to 20 inches of rain. These statistically rare events are often referred to as black swans. The renowned MIT Professor Yossi Sheffi (@YossiSheffi) writes, “Events that rarely happen but wreak havoc pose the most dangerous threat to corporate health. These may be called ‘black swans,’ a term popularized by Nassim Taleb in his 2007 book to describe occurrences that are thought to be impossible.”[2] Sheffi continues:

“Examples of such rare but high-impact events include Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the BP Horizon oil rig explosion in 2010, the 9/11 terrorist attack, and the tsunami that hit Japan in 2011. [And, in October 2015], South Carolina was hit by what Gov. Nikki Haley called the worst rains ‘in 1,000 years,’ causing record-setting floods and fatalities and shutting major transportation corridors.”

Russ Banham adds, “Black swans are, of course, those highly improbable but painfully consequential events that strike from the blue — or from the streets of Cairo, or from an offshore oil rig, or from a poorly designed car part.”[3] He continues:

“They can destroy a company’s reputation, cripple its financial performance, and perhaps even kill it outright. Because they are rare and almost impossible to predict, black-swan events tend to fall outside the scope of most companies’ risk-management programs (assuming a company has such a program at all).”

Ann Grackin, from ChainLink Research, insists that just because some events are rare it doesn’t mean that we can’t or shouldn’t forecast them. That may sound oxymoronic, but Grackin writes, “Creating a resilient enterprise is critical to customer protection and employee welfare, as well as securing the financial viability of the company. Yet many firms think that since rare events are unpredictable, then there is no sense in doing much about them other than ‘risk transfer’ (purchasing a risk product, if one is available, such as product liability, property and casualty and so on). … Modelers and forecasters look through a faulty lens; they discount these events because they are rare.”[4] Drawing from Taleb’s work, Grackin goes on to argue that forecasts can take into account rare events using history and a little common sense as a guide. She concludes:

“Crying out ‘Black Swans’ may be chic, but many of those who do may not understand Mr. Taleb. He challenges the notion that these are random and therefore unpredictable events, so we can’t plan and predict better to avoid being impacted. His perspective is that they are not as random as you think and that a lot of common sense — and evidence in plain sight — would lead people to more enlightened behaviors and preventions.”

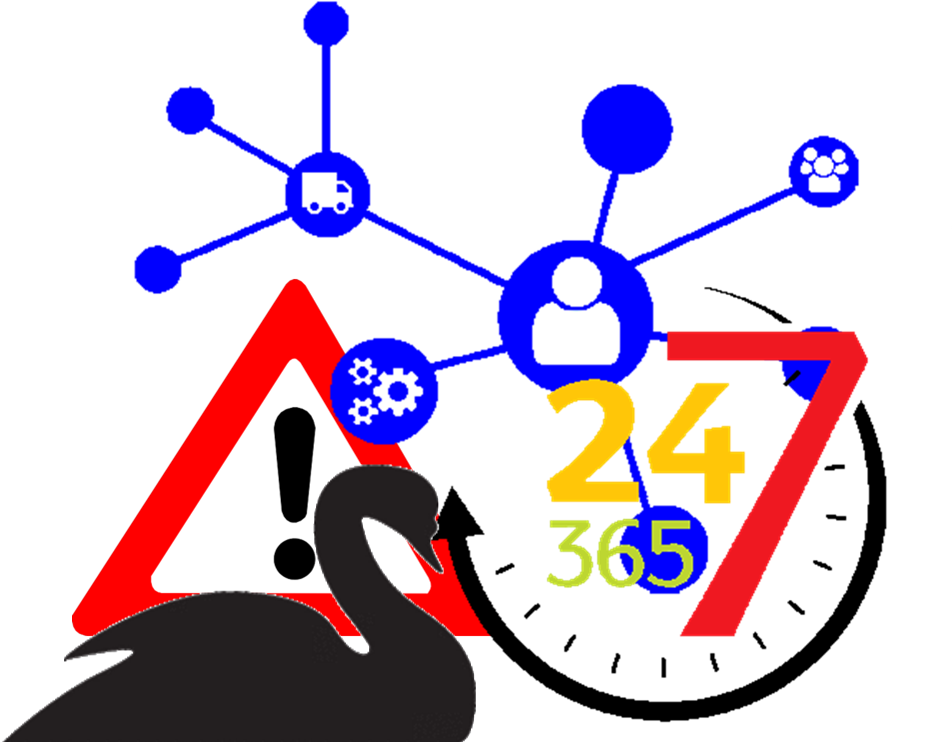

I agree with Grackin. We know that bad things can and will happen and any supply chain risk management system worth its salt will have some way of dealing with so-called black swan events. Katherine Noyes (@noyesk) agrees with Grackin’s position. “While such events are unlikely,” she writes, “the probability that they’ll happen isn’t zero — as history has proven again and again.”[5] Noyes knows, however, that getting a handle on black swan events (or any other potential event that could disrupt the supply chain) isn’t a simple matter. “It’s not easy to connect all the dots,” she writes. “A large enterprise can have thousands of suppliers, for instance, and each of those companies may have suppliers of their own. With all those moving parts, managing all the places disaster can strike is a complex matter.”

That’s why I believe that cognitive computing systems will play a significant role in supply chain risk management systems in the years ahead. Cognitive computing systems can handle many more variables than previous systems could handle. They can integrate structured and unstructured data and then analyze that data for insights or for warning signs of a pending disruption. In today’s fast-paced business world — characterized by supply chains stretched around the globe — companies need a system that improves visibility and remains alert 24 hours a day looking for potential problems. Of course, having an alerting system is only part of good supply chain risk management program. The most important part of the program is establishing what to do when an event is imminent or underway. A plan that sits on the shelf gathering dust is little better than having no plan at all. Sheffi notes, “Black swans … are never rehearsed because they are perceived as beyond-the-pale disruptions. Yet the likelihood of a black swan is not zero.” I recommend that every company with an extended supply chain conduct some “what if” exercises that include black swan events. Sheffi reminds business leaders of “three principles [that] are important to keep in mind in this context.” They are:

“First, statistical reasoning, the basis for most forecasting, is based on history, which may not repeat itself. Second, the worse disruption will always take place in the future (because the past is bounded and the future is not). Lastly, lack of evidence of a possible disruption is not the same as evidence of lack of potential disruption. The changing nature of supply chains has made it more important to consider the potential impact of the black-swan event, even if the events themselves are difficult to imagine.”

Because black swan events are difficult to imagine, “what if” exercises probably won’t get scenarios exactly right; but, that doesn’t really matter. Exercising on-the-fly problem-solving skills will make any supply chain risk management professional better and the SCRM program he or she supports more resilient to whatever may happen in the future. Sheffi elaborates:

“Creating and maintaining an emergency operations center ensures that a response can be triggered quickly. Knowing who to call to staff the center when a crisis hits is critically important. Supply-chain professionals who possess a deep and wide familiarity with the company’s operations and processes, and engineers who can qualify new suppliers and materials quickly, should be on the team. Likewise, the ability to quickly identify a disruptive event and to respond immediately is critical to a company’s efforts to keep global operations running and to recover.”

Knowing how your company will handle the really hard cases makes handling the easier cases less stressful. With the clock speed of business continually getting faster, having a system that is always monitoring the situation looking for anomalies and capable of alerting decision makers to problems in near-real-time is going to be essential in the decades ahead. Only cognitive computing systems can fill the bill for a state-of-the-art supply chain risk management system.

Footnotes

[1] U.S. Geological Survey, “Floods: Recurrence intervals and 100-year floods,” U.S. Department of the Interior, 19 August 2015.

[2] Yossi Sheffi, “Guest Voices: Black Swans and the Risks in Supply Chains,” The Wall Street Journal, 28 October 2015.

[3] Russ Banham, “Disaster Averted?” CFO Magazine, 1 April 2011.

[4] Ann Grackin, “Black Swan? Hardly! Revolutions and Tsunamis Come and Go!” ChainLink Research, 5 April 2011.

[5] Katherine Noyes, “Beware the ‘black swans’ in your supply chain,” CIO, 30 October 2015.