If Tom Vander Ark (@tvanderark), CEO of Getting Smart, is correct, we need to start preparing our children for a future in which a significant portion of the workforce freelances, moving from project to project as their interests change. “Four of 10 young people in high school will end up freelancing,” he claims, “another four will manage projects inside organizations — either way, it’s a project-based world.”[1] Whether or not Vander Ark is correct in his prediction about the number of freelancers who will make up the future workforce, he is spot on in his belief that it’s a project-based world. That’s why I, along with a few colleagues, founded The Project for STEM Competitiveness — to help get a project-based, problem-solving approach into schools near where we live. We firmly believe that by showing students how STEM subjects (i.e., science, technology, engineering, and math) can help them solve real-world problems they will begin to appreciate the opportunities that STEM skills open for them. Vander Ark is excited about the future; which he believes will be characterized by an innovation economy. To succeed in the innovation economy, Vander Ark asserts that students need to be instilled with an innovation mindset. He indicates that an innovation mindset is the result of developing three other mindsets that emphasize effort, initiative, and collaboration.

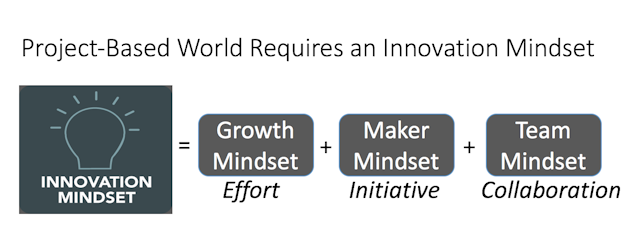

Each of those attributes (i.e., effort, initiative, and collaboration) are developed in a curriculum that features project-based STEM education. Matthew Randazzo (@MjRandazzo), Chief Executive Officer of the National Math and Science Initiative, believes we need to start developing these attributes at the earliest stages our children’s educational journey. He writes, “If we are to reach for the stars, and if we are to secure our nation’s future as a global leader in innovation and economic prosperity, our investment lies not only in our workforce development and the strength of our engineering and space programs, but also in our youngest learners.”[2] I believe Randazzo’s statement is true whether we are discussing the future of space exploration or the development of new consumer products. Randazzo continues:

“Research shows engaging students early in STEM topics is beneficial for two key reasons. First, when we wait until middle or high school to engage students in math and science, we miss out on a large group of students who had the potential to pursue STEM, but focused their interests elsewhere. This is particularly true for girls and students of color who are told, early and often, that STEM subjects somehow aren’t really for them. Science is inherently fascinating to young children who are curious about the world around them. However, without high-quality, age-appropriate science education in the early grades, that interest wanes as students move through school.”

The objective of early STEM education is not to encourage all students to seek jobs in those areas — after all, it would be a dull world indeed without people who love the arts. The purpose of STEM education is to equip students to face life’s challenges no matter the course they take. Vander Ark offers four examples of career progressions that demonstrate how being equipped with skills learned from a project-based curriculum can make the world a better place:

- After flirting with physics, Omar Bawa studied law and business. After working as a humanitarian lawyer, Bawa, now 24, launched Goodwall to help young people make good postsecondary decisions.

- Serving as an Americorp member in Arkansas helped Andrea Price appreciated the importance of youth wellness. After launching a campaign to fight hunger and a company to promote fitness, Price added a graduate degree and worked for a foundation before launching The Giving Net, a community development organization.

- Jon Merril attended culinary school and worked in four kitchens before getting the chance to open a restaurant as head chef. Two years later he sold everything to travel and launch Vagabundus Project, a cooking and travel web series.

- Over the last decade, journalist Andrea Wien contributed to a dozen publications while changing jobs every year or two before writing a book, Gap to Great, and founding a company to help young people consider and plan gap years.

“What do they have in common,” Vander Ark asks. “They move from project to project driven by curiosity and a desire to make a difference.” Katherine Prince (@katprince), a learning specialist at KnowledgeWorks, asserts we must prepare our students to flourish amidst uncertainty. “The world of work is changing rapidly,” she writes. “Those changes will have big implications for how we approach learning and what our education system aims to achieve. We increasingly organize work according to projects. The platform or gig economy means that more people are stitching together mosaic careers instead of working full-time for a single organization.”[3] Much of the uncertainty to which Prince refers will be the result of automation, artificial intelligence, and robotics. She explains:

“Artificial intelligence and machine learning are ushering in the rise of smart machines that will be able to carry out many of the complex cognitive tasks that once seemed exclusive to middle class work in the knowledge economy. Already, doctors are using deeper learning to help diagnose illnesses, entry-level lawyers are finding themselves out-analyzed by machines that can harvest case history faster than any human, artificial intelligence is writing news stories and robots are staffing restaurants. This is just the beginning: one Oxford University study suggests that as many as 47% of current middle-class American jobs could get displaced or change significantly over the next two decades due to automation. The rise of smart machines in the workplace will have a huge impact on human work, but the nature and extent of that impact remains uncertain.”

In fact, many (if not most) of the jobs our children will fill don’t exist today. The best way to prepare them to fill those jobs is by teaching them how to think critically and solve problems. STEM subjects do just that. Randazzo agrees. He writes, “By beginning STEM learning in younger grades, we help children develop systems thinking and problem solving, which are exactly the skills needed for their future success. … Our potential for solving society’s greatest challenges is tremendous. I, for one, look to our youngest generation with hope. It’s on us to nurture their passion and talents so they grow up to advance and apply STEM knowledge in ways beyond our imagination.” Prince concludes, “We need to redefine readiness for an uncertain future of work in which people’s desire for meaningful and authentic contribution will sit alongside and shape new platforms of exchange and value creation and a complex economic landscape. Let’s make sure education is ready.”

Footnotes

[1] Tom Vander Ark, “Developing Minds Ready for the Innovation Economy,” Getting Smart, 21 August 2016.

[2] Matthew Randazzo, “STEM Seeds Planted Early,” Huffington Post The Blog, 17 August 2016.

[3] Katherine Prince, “Redefining Career Readiness for an Uncertain Future,” Getting Smart, 19 August 2016.