In late October, President Barack Obama announced that the U.S. Government would provide $3.4 billion in grants to improve the nation’s electrical grid [“U.S. electrical grid gets $3.4 billion jolt of stimulus funding,” by Michael A. Fletcher, Washington Post, 28 October 2009]. Although I believe the President is committed to helping clean-up the environment, politics undoubtedly played a role in the announcement. The administration has been criticized because the stimulus package that it signed hasn’t generated anywhere near the number of jobs it had predicted. The President made it a point to reiterate his belief that green technologies would generate a significant number of jobs in the coming years. He stated that smart grid technology alone is “expected to create tens of thousands of new jobs all across America.” Fletcher reports:

“The federal money will pay for ‘smart meters,’ updated transformers and other devices to make the transmission of power more efficient and reliable. Obama called the grants the largest investment in energy-grid modernization in U.S. history. ‘There’s something big happening in America in terms of creating a clean-energy economy,’ he said.”

A smart grid, of course, doesn’t create clean energy. It simply allows a more efficient distribution of electricity. Utility companies hope that a smart grid will help them close the gap between current energy generation capabilities and the anticipated shortfall created by the delayed construction of new powerplants. There won’t be simply one “smart grid” but many; and that will create other challenges that I will discuss below. Smart grids will help close the capacity gap by providing consumers and utility companies more control over where power comes from and how and when it is used.

“Obama’s vision for changing energy habits and reducing U.S. dependence on fossil fuels, especially foreign oil, relies on establishing a national ‘smart grid’: an array of switches, sensors and computer chips that will be installed at various stages in the energy-delivery process. But no less important to the administration are the job-creation aspects of the investments. With the nation’s unemployment rate at 9.8 percent and projected to rise, energy technology promises a bounty of new jobs.”

Back in the June, The Economist published an article that asserted “by promoting the adoption of renewable-energy technology, a smart grid would be good for the environment—and for innovation” [“Building the smart grid,” 6 June 2009 print issue]. The article began by highlighting what analysts have been saying for some time, electrical grids around the world need a major facelift in order to meet the needs of the future. The article reported:

“There is a problem lurking in the power grid that links [energy sources] together. Green sources of power tend to be distributed and intermittent, which makes them difficult to integrate into the existing grid. And when it comes to electric cars, a study by America’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) found that there is already enough generating capacity to replace as much as 73% of America’s conventional fleet with electric vehicles—but only if the charging of those vehicles is carefully managed. In order to accommodate the flow of energy between new sources of supply and new forms of demand, the world’s electrical grids are going to have to become a lot smarter.”

The article noted that electrical grids “have changed very little since they were first developed more than a century ago.” Of course, for most of those years there was very little reason to change. Capacity was sufficient to meet customer needs so grids simply connected power plants on one end and consumers on the other. But The Economist notes that that industrial approach “is now showing its age.”

“One problem is a lack of transparency on the distribution side of the system, which is particularly apparent to consumers. Most people have little idea how much electricity they are using until they are presented with a bill. Nor do most people know what proportion of their power was generated by nuclear, coal, gas or some form of renewable energy, or what emissions were produced in the process. In the event of a power cut, it is the customer who alerts the utility, which then sends out crews to track down the problem and fix it manually. ‘I can’t think of another industry that still has that lack of visibility over its networks,’ says Heather Daniell of New Energy Finance, a research firm in London.”

Grid capacity is also a growing issue. Utility companies are more willing to build generating capacity than transmission capacity because they benefit solely from the former but often have to share with others the capacity of the latter. In many ways, electric grids are part of the commons that provide broad benefits to the areas they serve. In the future, a lot more capacity is going to be needed.

“According to projections from America’s Energy Information Administration, electricity generation around the world will nearly double from about 17.3 trillion kilowatt-hours (kWh) in 2005 to 33.3 trillion kWh in 2030. Poor countries will show the strongest growth in electricity generation, increasing by an average of 4% per year from 2005 to 2030, compared with 1.3% per year for their richer counterparts. In some countries, including America, the grid has not kept up with the growth in demand for power. The deregulation of America’s utilities in the 1990s encouraged companies to transfer power over long distances. At the same time, regulatory uncertainty and increased competition led to reduced investment in new transmission lines. As a result, some parts of the system have become increasingly congested.”

As I noted above, part of the capacity conundrum can be handled by using the grids more intelligently. That idea forms the basis of all smart grids.

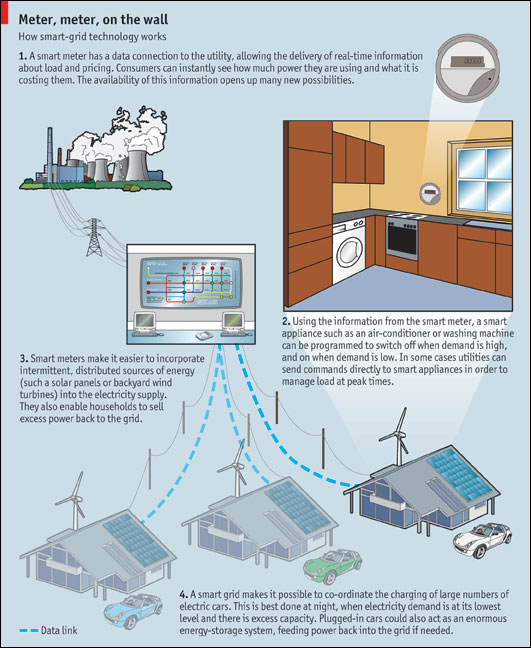

“Adding digital sensors and remote controls to the transmission and distribution system would make it smarter, greener and more efficient. Such a ‘smart grid’ or ‘energy internet’ would be far more responsive, interactive and transparent than today’s grid. It would be able to cope with new sources of renewable power, enable the co-ordinated charging of electric cars, provide information to consumers about their usage and allow utilities to monitor and control their networks more effectively. And all this would help reduce greenhouse-gas emissions.”

The article was accompanied by an excellent schematic about how smart grids work (see below). The accompanying text notes that many of the changes introduced by the smart grid would be invisible to the consumer, but their effects would be revolutionary.

“Today’s supervisory control and data acquisition systems, for example, typically provide data on the state of transmission lines every four seconds. Devices called synchrophasors can sample voltage and current 30 times a second or faster—giving utilities and system operators a far more accurate view of the health of the grid. A broad deployment of synchrophasors could be used as an early warning system to help halt or prevent power surges before they develop into massive blackouts. … Other smart-grid technologies would be more visible to consumers. Probably most important would be the introduction of smart meters, which track electricity use in real-time and can transmit that information back to the power company. … Smart meters establish a two-way data connection between the customer and the power company, by sending information over a communications network that may include power-line, radio or cellular-network connections. Once smart meters are installed, power companies can determine the location of outages more easily, and no longer need to send staff to read meters, or to turn the power on or off at a particular property. … But the smart meter is only the first step. Eventually smart meters will communicate with smart thermostats, appliances and other devices, giving people a much clearer view of how much electricity they are consuming. Customers will be able to access that information via read-outs in their homes or web-based portals, through which they will be able to set temperature preferences for their thermostats, for example, or opt in or out of programs that let them use cleaner energy sources, such as solar or wind power.”

One of the more controversial aspects of a smart grid is that it will allow utility companies to implement variable pricing — i.e., charging customers more electricity when usage in high in the hopes they will turn off some of the power consuming gadgets. This worries some consumer advocates who argue that older people on fixed incomes and who are more vulnerable to high or low temperatures could suffer because they couldn’t afford to heat or air condition their homes when they most need to. The utility companies believe the system will be flexible enough that they will be able to make adjustments in those cases. That, however, remains to be seen. What studies have shown is that people who “are made aware of how much power they are using, … reduce their use by about 7%. With added incentives, people curtail their electricity use during peaks in demand by 15% or more.” This all sounds complex — and it is. But the utility companies are telling consumers to soldier up and accept it.

“‘If you don’t want to participate, then you’re going to pay a much higher rate per kilowatt-hour,’ says Peter Corsell of GridPoint, a company that has developed a web-based portal that lets people respond to price changes from utilities. ‘And if you want to opt in, you may save a whole lot of money.’ During a one-year pilot study carried out by PNNL, for example, consumers reduced their electricity bills by an average of 10% compared with the previous year.”

The $3.4 billion in grants announced by the President sounds like a lot of money — and it is — but it’s not enough to implement a national smart grid fully. In fact, it’s only a drop in the bucket. The Economist continues:

“Implementing all this will not be cheap. A smart meter costs about $125, and can cost several hundred dollars more to install, once the necessary communications network and data-management software at the utility are taken into account. (Smart meters can collect customer readings as often as every 15 minutes, rather than every month, so utilities need new software to cope with all the extra data.) The American government is spending some $4 billion from its economic-stimulus package on smart-grid initiatives, but providing a smart meter for every American home would cost far more: California’s investor-owned utilities alone are spending about $4.5 billion on deploying smart meters over the next few years. That implies that a nationwide implementation could cost around $50 billion. But PNNL estimates that $450 billion would have to be poured into conventional grid infrastructure to meet America’s expected growth over the next decade anyway.”

The article goes on to note “that power companies are understandably reluctant to invest in technologies that will reduce consumption of the product they sell, even if there are other benefits.” That’s certainly understandable; but proponents of the smart grid say that reluctance can be overcome when companies can be shown that resulting efficiencies help recoup investments quickly and increase profits over the long run.

“As well as producing savings from improved operational efficiency, a smart grid could also save utilities money by reducing consumption, and with it the need to build so many new power stations. Reducing peak demand in America by a mere 5% would yield savings of about $66 billion over 20 years, according to Ahmad Faruqui of the Brattle Group, a consultancy that has worked with utilities on designing and evaluating smart-meter pilot programs. Moreover, studies have shown that the best in-home smart-grid technologies can achieve reductions in peak demand of up to 25%, which would result in savings of more than $325 billion over that period, calculates Dr Faruqui. ‘Technology is expensive,’ he says, ‘but not using it will be even more expensive.’ Smart-grid technology offers a wide range of possibilities, so deployments will vary depending on each utility’s business needs, existing infrastructure and regulatory environment.”

The article reports that unlike the Internet which is built on open standards, no such standards have been agreed upon for operating smart grids. That could pose a challenge for grids that are expected to work together to distribute power throughout a large country like the United States.

“Some standards exist, but others are just emerging, says Don Von Dollen of the Electric Power Research Institute, whose organization was recently asked by America’s National Institute of Standards and Technology to develop a ‘smart-grid interoperability standards road map’. Agreed-upon standards would allow companies to buy and sell devices, services and software in the knowledge that they would work together. One area where such interoperability will be critical is in the home. Many utilities want people to be able to buy smart thermostats, smart appliances and other smart-grid technologies in shops, says Sam Lucero of ABI Research, ‘and if everything is proprietary that becomes much more problematic.’ … Once these issues are ironed out, though, the smart grid could provide the platform for a huge range of innovation and applications in energy, just as the internet did in computing.”

Whether you love technology or hate it, smart grids are coming. Most analysts believe that consumers who embrace smart grid technology will actually save money and help the environment. As they say in the sports world, “no pain, no gain.” There will be some growing pains associated with the implementation of smart grids, but the gains should be worth it.