If there weren’t winners (i.e., people who profit) in or from conflict situations, we would have much less conflict. The truth is, however, that there are winners and there are losers. In some cases, the winners win only if conflict continues. They have no interest in seeking victory or ultimate peace. In their seminal work in this area [“Dealing with Obstructionist Leaders,” Civil Wars, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Autumn 1998), pp. 65-94], Donald Daniel and Bradd Hayes assert that often the profiting obstructionists are individuals or oligarchies who profit at the expense of the rest of society. They wrote:

“Factional leaders can benefit not only politically from the continuation of conflict, but economically as well. Their control of movement and of what what passes for law and order in particular areas means that they also control its economic lifelines. … Faction leaders are usually best positioned to engage in such activities or, for a fee, to enable others to do so. … There are more than just warlords who can benefit from continuation of chaos and instability. Some combatants enjoy or only know a life where the life brings respect and material support. The prospect of pursuing peacetime employment may seem not only unattractive, but also make them insecure. Alongside them are profiteers, arms dealers, and employees of aid organizations, such as ‘drivers, secretaries, warehouse guards, programme staff, liaisons with authorities, who may find their survival threatened by the cessation of conflict and the resultant withdrawal of emergency assistance.’ They may turn against any leader whose willingness to pursue peace threatens their instability-based lifestyle.”

Jeffrey Gettleman reports that all or most of these obstructionist challenges can be found today in Somalia [“People Who Feed Off Anarchy in Somalia Are Quick to Fuel It,” New York Times, 25 April 2007]. He writes:

“Beyond clan rivalry and Islamic fervor, an entirely different motive is helping fuel the chaos in Somalia: profit. A whole class of opportunists — from squatter landlords to teenage gunmen for hire to vendors of out-of-date baby formula — have been feeding off the anarchy in Somalia for so long that they refuse to let go. They do not pay taxes, their businesses are totally unregulated, and they have skills that are not necessarily geared toward a peaceful society. In the past few weeks, some Western security officials say, these profiteers have been teaming up with clan fighters and radical Islamists to bring down Somalia’s transitional government, which is the country’s 14th attempt at organizing a central authority and ending the free-for-all of the past 16 years. They are attacking government troops, smuggling in arms and using their business savvy to raise money for the insurgency. And they are surprisingly open about it.”

The extent of obstructionist cynicism is incredible. Gettleman provides a few examples:

“Omar Hussein Ahmed, an olive oil exporter in Mogadishu, the capital, said he and a group of fellow traders recently bought missiles to shoot at government soldiers. ‘Taxes are annoying,’ he explained. Maxamuud Nuur Muradeeste, a squatter landlord who makes a few hundred dollars a year renting out rooms in the former Ministry of Minerals and Water, said he recently invited insurgents to stash weapons on ‘his’ property. He will do whatever it takes, he said, to thwart the government’s plan to reclaim thousands of pieces of public property. ‘If this government survives, how will I?’ Mr. Muradeeste said. Layer this problem on top of Somalia’s sticky clan issues, its poverty and its nomadic culture, and it is no wonder that the transitional government seems to be overwhelmed by the same raw antigovernment defiance that has torpedoed earlier attempts at stabilizing the country.”

While most of the civilian population longs for peace and stability, these obstructionists are doing their best to ensure it never emerges. As their profits rise, so does the toll of innocent victims. Gettleman reports that resistance has recently increased, primarily because of international pledges supporting the transitional government (all part of the war on terrorism). As Tom Barnett points out, nefarious actors are wont to set up shop in the most disconnected parts of the world — that pretty well describes Somalia. The fact that Somalia is disconnected politically from the international community doesn’t mean that it is completely dysfunctional. Somalis are surprisingly resilient:

“Somalis are legendary individualists, and when the central government imploded in 1991, people quickly devised ways to fend for themselves. Businessmen opened their own hospitals, schools, telephone companies and even privatized mail services. Men who were able to muster private armies, often former military officers, seized the biggest prizes: abandoned government property, like ports and airfields, which could generate as much as $40,000 a day. They became the warlords. Many trafficked in guns and drugs and taxed their fellow Somalis. Beneath the warlords were clan-based networks of thousands of people — adolescent enforcers, stevedores, clerks, truck drivers and their families — all tied into the chaos economy. Ditto for the freelance landlords and duty-free importers.”

Efforts to replace this ad hoc situation with a more formalized and traditional system of government has proved elusive. The opportunists have been ruthless and law abiding businessmen have suffered under their despotism. One reason that Islamists received strong support in Mogadishu, the would-be capital of Somalia, is that they provided a secure environment and reduced corruption.

“Many in the business community became fed up with paying protection fees to the warlords and their countless middle-men. Business leaders then backed a grass-roots Islamist movement that drove the warlords out of Mogadishu last summer and brought peace to the city for the first time in 15 years. The Islamists seemed to be the perfect solution for the businessmen. They delivered stability, which was good for most business, but they did not confiscate property or levy heavy taxes. They called themselves an administration, not a government.”

For those living in Mogadishu, those were the best and most peaceful months they had enjoyed for years. Optimism filled the streets. It all came tumbling down, however, when more radical factions assumed control:

“But then a radical wing took over, and the Islamists declared war on Ethiopia, which commands one of the mightiest armies in Africa. The Ethiopians, with covert American help, crushed the Islamist army in December and bolstered the authority of Somalia’s transitional government in the capital. Many residents initially welcomed the transitional government. But then it made some questionable calls that cut across clan and business lines. It abruptly closed ports and took over airfields belonging to Hawiye businessmen, denying them revenue they had been accustomed to receiving for years. Many Somalis began to worry that the transitional government, which includes elders from all of Somalia’s clans, was being pushed around by the Darod, the clan of the transitional president and a historic rival to the Hawiye.”

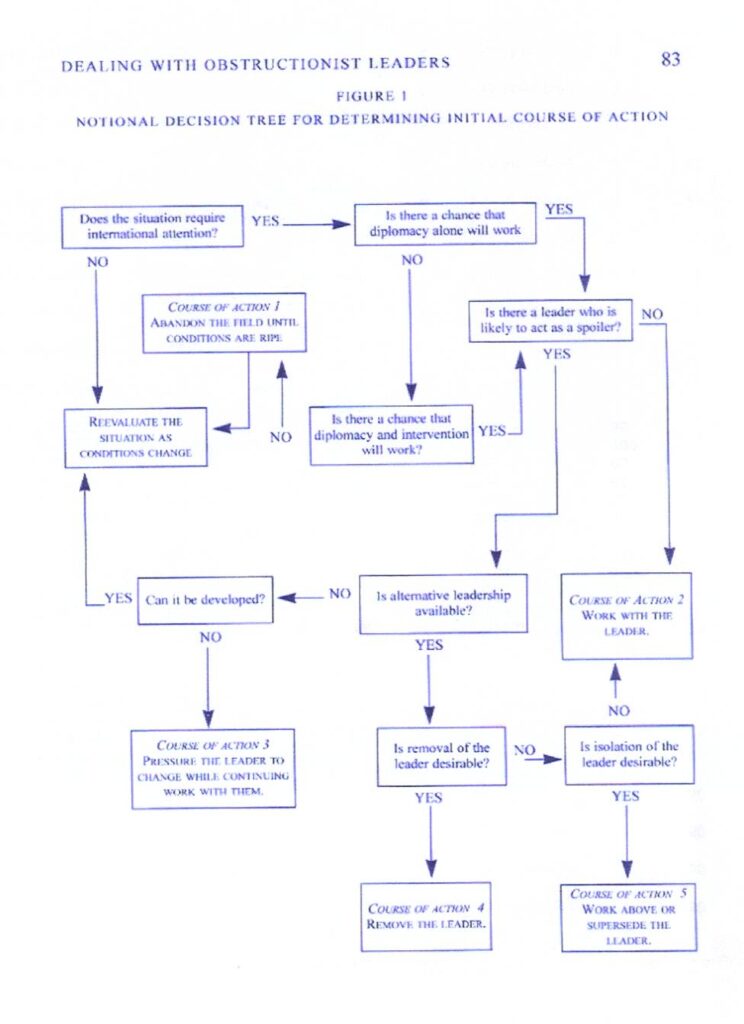

Security is once again an issue in the capital and some people are even required to pay a fee for seeking relief in the shade of a tree claimed by an opportunist. Daniel and Hayes developed a simple decision tree to help select a strategy for dealing with obstructionist leaders. The problem in Somalia, however, is that a decade of anarchy has created so many obstructionists that no single course of action is sufficient to deal with the challenge. Any likely solution will involve co-opting opportunists by providing them a continued stream of revenue while rebuilding a government and its capacities from the bottom up.

Security is once again an issue in the capital and some people are even required to pay a fee for seeking relief in the shade of a tree claimed by an opportunist. Daniel and Hayes developed a simple decision tree to help select a strategy for dealing with obstructionist leaders. The problem in Somalia, however, is that a decade of anarchy has created so many obstructionists that no single course of action is sufficient to deal with the challenge. Any likely solution will involve co-opting opportunists by providing them a continued stream of revenue while rebuilding a government and its capacities from the bottom up.

As unpalatable as this option appears, over a decade of violence has left the foundations of Somalia in ruins. Even traditional tribal governance has not been able to fill the gap. Obstructionists obstruct whenever they have something to lose. Any winning strategy for peace in Somalia must provide obstructionists with a reason to support peace. It must give them a stake in Somalia’s peaceful future or eliminate them. The latter strategy has not worked, even when the international community turned its attention to eliminating them. If anyone needs a lesson about why ignoring instability in “nonstrategic” nations is bad foreign policy, they need look no further than Somalia. Nothing good can emerge from such instability and, in a globalizing world, tendrils from such instability inevitably stretch from what Tom Barnett calls the Gap (the world’s undeveloped areas) into the Core of the developed world.