With gasoline and diesel prices hovering between $3 and $4 per gallon, some trucking firms have reduced capacity to ensure that more loads are filled. With capacity at a premium and rates high, supply chain professionals continue to examine ways to reduce transportation costs. This is just one of many challenges with which they must wrestle. Those challenges become even more difficult if company executives fail to heed recommendations. Mark Meier, Manager of Implementation and Assessment at CH Robinson Worldwide (CHRW), claims that supply chain professionals often have a difficult time convincing C-level executives to take recommended courses of action because they don’t understand logistics. He writes, “Literacy rates are high in the C-suite when it comes to functions such as sales or marketing, but in many companies logistics terms don’t tend to trip off the tongue in senior-level meetings.” [“Change Agent: A Challenging Role for Freight Management,” Logistics Viewpoints, 23 June 2011] Meier provided the following example of what he is talking about:

“In a recent project a company was having problems with the cost of its outbound finished goods. The enterprise shipped raw materials into its facility by road, and the trucks usually left empty. An obvious solution – obvious, that is, to practitioners – was to use the empty trucks to carry finished goods on the outbound leg. But managers, even at a senior level, found it difficult to understand that they were already paying for empty backhauls and the outbound solution was a cost-effective strategy. Most freight managers would have discerned that in such a situation the carrier bringing empty trucks home was probably charging the shipper a rate premium based on their location. While the carrier was not overlooking the cost of positioning its equipment – it understood the importance of maximizing equipment utilization – the transportation buyer was seemingly unaware of this expense.”

In order for the above example to work, of course, tractor trailer combinations hauling raw materials into the factory need to be the type required to haul finished goods outbound. Smart people, however, could easily find a compromise solution that would benefit both the manufacturer and the trucking company. Meier claims, however, that the smartest people sometimes aren’t available. He writes:

“Departments that are detached from logistics and regard freight-related activities as being well beyond their sphere of influence may not be motivated to send their brightest folks to, say, the implementation of a new transportation management system. They might see trucks moving in and out of the company’s facilities, but do not make the connection with their responsibilities.”

The solution, Meier says, “requires effective education and communication, and working with customer stakeholders to identify and recruit the right team members.” He concludes:

“The management of freight affects virtually every part of an enterprise. Helping organizations to appreciate this might be the most difficult change management challenge of all for transportation professionals.”

With transportation costs remaining high, one needs to ask, “Are things changing in the transportation management arena?” According to Adrian Gonzalez they are. [“Take a Different View of Transportation Procurement Solutions,” Logistics Viewpoints, 16 March 2010] He writes:

“Historically, transportation procurement was a strategic engagement for most companies, a process conducted every two years or so. At the end of the engagement, companies would enter their new rates and preferred carriers into their TMS, or they would publish a routing guide, and then they would focus on execution until the next contract renewal cycle.”

The latest TMS trends, Gonzalez writes, involve terms like “self-service/do-it-yourself and software-as-a-service.” One reason that transportation management systems are becoming more tactical than strategic is because the current logistics landscape is ever changing. He continues:

“Things change after a transportation procurement engagement is completed: capacity requirements in a given lane might be significantly greater than anticipated; new lanes are added to your network; preferred carriers are rejecting too many tenders in certain lanes or their service levels are degrading; and so on. These are the type of performance data that companies should be tracking using their TMS dashboards (and if they are not using a TMS, well, shame on them!). Addressing these issues often requires conducting ‘mini bids’ to add capacity, find alternate carriers, and obtain rates for new lanes. And that’s what these new breed of transportation procurement solutions are well designed to address—i.e., they are an affordable, easy-to-use-and-deploy alternative to spreadsheets and fax machines.”

Once goods are out the door and loaded on a truck where do they go? Truckload shipments can go to a traditional warehouse/distribution center, a crossdock distribution center or direct to the retailer. How does a company decide which model is most effective and efficient? In the retail sector, crossdocking is the most common solution. According to the folks at Supply Chain Digest, however, outside of the retail sector, “examples of true crossdocking” are difficult to find. [“Understanding Retail Distribution Models,” 4 January 2011] The Supply Chain Digest article focuses on the research of Dr. Kevin Gue of Auburn University. Dr. Gue explains the “three primary models for delivering goods to retail stores” this way:

“1. Traditional Warehousing/Distribution, in which vendors ship goods to retail DCs, where the goods are stored until store orders need fulfilled, where they are then picked (often using a ‘wave process’ for batches of stores) and delivered to the stores.

“2. Crossdock DCs, in which shipments from inbound suppliers are moved directly to outbound vehicles, with very little if any storage in between. In the best possible situation, products never touch the floor or a shelf, though some amount of staging is often used.

“3. Direct to Store Delivery, in which vendors ship goods directly from their own facilities to retail store outlets.”

The Supply Chain Digest staff notes, “In reality, many if not most retailers probably use some type of hybrid system, with an increasing number of them, for example, running both crossdock and traditional distribution operations in a single facility, which many thought too difficult to manage in the past.” The article discusses some other models as well:

“Home products giant Home Depot, as another example, is substantially through a multi-year project to transform its model from one in which some 75% of goods were delivered by vendors direct to its stores and 25% from Home Depot DCs to the exact reverse of that. Home Depot is using a new network of crossdock-focused Regional Distribution Centers (RDCs) to get that job done. Another model that is emerging is the so-called ‘DC Bypass’ approach for imported goods, in which import DCs would transload the arriving containerized goods for manufacturers and ship the imported products directly to retail DCs – and maybe even retail stores – without the products moving into the manufacturer’s distribution network at all.”

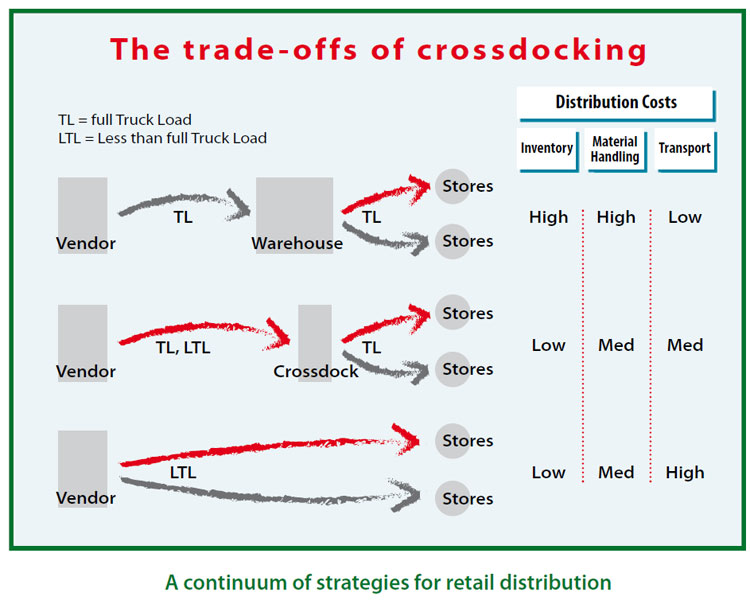

Returning to Dr. Gue’s work, the article notes that Gue “has nicely summarized the pros and cons of each approach in a summary graphic, as shown below.”

Concerning the chart and Gue’s conclusions, the article states:

“Looking at the chart, it might initially appear that the traditional distribution approach is the most costly – and while it clearly is from a handling only perspective, there are other considerations, Gue says. Direct-to-store, he notes, has the disadvantages of some loss of control of stock availability, high costs of receiving at stores (imagine weekly shipments from every vendor), and often much higher transportation costs, since vendor shipments often use expensive less-than-truckload or parcel shipment modes. The crossdock model also has some downsides. It also sacrifices some inventory control by not holding buffer stock between the vendor and store, but unlike shipping direct-to-store it maintains transportation efficiencies by consolidating small shipments into full truckloads for store deliveries. While the benefits of reducing an entire layer of network inventory through the crossdock model are huge, there are other factors that must be considered, Gue says. For example:

“(1) Lead time from order to delivery at the store is longer than with traditional distribution, so stores typically have to hold slightly more stock to hedge against stockouts. If vendors are far away, lead time could be several days.

“(2) Unlike direct delivery from vendors, crossdocking requires the retailer to buy (or lease) and operate crossdocks, or to pay a third-party logistics provider to do so.

“(3) Crossdocking requires greater coordination with vendors, sometimes with painful details of implementation.

“Still, the trend clearly seems to be towards greater use of crossdocking in retail.”

In a follow-on article, the staff at Supply Chain Digest examined Professor Gue’s “thoughts on where the crossdock model usually has its best fit, and keys to making it a success.” [“Where does Crossdocking have the Best Operational Fit?” 11 January 2011] The article continues:

“So where does crossdocking have the best fit in terms of retail distribution? Gue offers several guidelines:

“Use crossdocking for products with high, stable demand: If demand is fairly constant, then the inventory serves little purpose, and the product is a good candidate for crossdocking. If demand is highly variable or the cost of a stockout is high, then traditional warehousing is probably the best strategy, Gue says.

“Use crossdocking for products for which customers are willing to ‘wait a few days’: This is typical for larger purchase items such as major electronics or appliances. In fact, crossdocking is an essential strategy of Whirlpool’s totally redesigned distribution network, enabling the appliance giant to deliver washers and refrigerators to every household in the US in just two days. Gue notes that when a ‘stockout’ in a store does not mean a lost sale, crossdocking can become very attractive.

“Push distribution systems should crossdock everything that can be sold in stores now: This model is especially associated with heavy discount retailers, such as Ross Dress for Less or TJMaxx, where merchandise is acquired at a discount and everything is pushed to the stores. Customers are used to constantly changing merchandise and inventories. Gue says warehouse club stores such as Costco and Sam’s Club take a similar distribution approach for many of their SKUs. When customers have a low expectation that any particular item will be in stock, it is a ‘perfect situation’ for cross docking, Gue says.”

Professor Gue states that “the crossdock model is an attractive and powerful option for many retailers,” but he advises that “it has its share of challenges.” Those challenges include:

“• Material handling decisions: Poor material handling practices can eat away at much of the potential crossdock savings. What the level of automation should be, especially for crossdocking at the carton level, is a key management decision. Dock congestion can be a big problem, Gue adds. Costco acquired special pallet jacks capable of moving four or even eight pallets at a time to power its crossdock operation, for example.

“• Cost analysis: Really understanding the potential savings overall and by product and/or vendor is not easy, especially as the inventory savings can be very difficult to estimate in practice. Gue notes Home Depot analyzed vendors one by one to determine which would participate in its new the crossdocking program. Where there wasn’t a strong benefit, the vendors products would be kept direct to store or handled through traditional distribution.

“• Vendor management: Vendors play an essential role in a crossdocking program’s success. Understanding each vendor’s IT, value-added services, and overall distribution capabilities is essential to avoid many costly and unpleasant surprises down the road.”

Like most segments of the supply chain, there is no silver bullet answer that covers all companies and all situations. Gue admits that “for most retailers, the right approach is probably a combination of all three” distribution models.