Three lakes in Africa (Lake Monoun, Lake Nyos, and Lake Kivu) are infamous for being subject to limnic eruptions. A limnic eruption, sometimes called lake overturn, is a natural disaster during which carbon dioxide (CO2) suddenly erupts from deep lake water. These eruptions suffocate wildlife, livestock and humans. There have been two such eruptions in the last 30 years. The first disaster, which killed 37 people, took place during the night of 15 August and the morning of 16 August 1984 in and around Lake Monoun. Because limnic disasters are rare, the cause of the deaths was at first shrouded in mystery. The mystery was solved two years later when a much larger limnic eruption took place in Lake Nyos. In that disaster, some 1.6 million tons of CO2 was released in deadly cloud. Evidence showed that “the gas spilled over the northern lip of the lake into a valley running roughly east-west from Cha to Subum, and then rushed down two valleys branching off it to the north, displacing all the air and suffocating some 1,700 people within 25 kilometres (16 mi) of the lake, mostly rural villagers, as well as 3,500 livestock.” [“Lake Nyos,” Wikipedia].

Unlike the earlier tragedy at Lake Monoun, the disaster at Lake Nyos made headlines around the world. Pictures, like the attached image, documented the disaster that left people and livestock littered across an otherwise undamaged landscape. Having two such events linked so closely together is surprising since scientists have determined that such events normally cause “living creatures in the lake[s] to go extinct approximately every thousand years.”

Unlike the earlier tragedy at Lake Monoun, the disaster at Lake Nyos made headlines around the world. Pictures, like the attached image, documented the disaster that left people and livestock littered across an otherwise undamaged landscape. Having two such events linked so closely together is surprising since scientists have determined that such events normally cause “living creatures in the lake[s] to go extinct approximately every thousand years.”

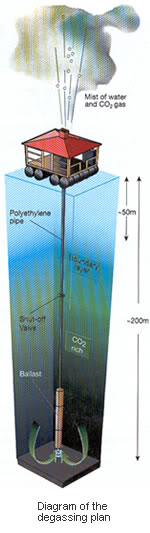

Despite the rarity of limnic eruptions, governments were eager to find a way to prevent such disasters from reoccurring. Accordingly, “scientists spent the next decade trying to figure out a way to safely release the gas before disaster struck again. They eventually settled on a plan to sink a 5 1/2-inch diameter tube down more than 600 feet, to just above the floor of [Lake Nyos]. Then when some of the water from the bottom was up to the top of the tube, it would rise high enough in the tube for the CO2 to come out of solution and form bubbles, which would cause it to shoot out the top of the tube, blasting water and gas more than 150 feet into the sky. Once it got started, the siphon effect would cause the reaction to continue indefinitely, or at least until the CO2 ran out. A prototype was installed and tested in 1995, and after it proved to be safe, a permanent tube was installed in 2001.” [“Lake Nyos–The Deadly Limnic Eruption“] According to the article (written in 2006), the tube is working but at least an additional five tubes are needed to reduce the levels of carbon dioxide to safe levels. A similar tube was installed in Lake Monoun in 2004, but an additional tube is also needed there. A quick search of the Web didn’t turn up any evidence that the additional tubes have been installed.

Despite the rarity of limnic eruptions, governments were eager to find a way to prevent such disasters from reoccurring. Accordingly, “scientists spent the next decade trying to figure out a way to safely release the gas before disaster struck again. They eventually settled on a plan to sink a 5 1/2-inch diameter tube down more than 600 feet, to just above the floor of [Lake Nyos]. Then when some of the water from the bottom was up to the top of the tube, it would rise high enough in the tube for the CO2 to come out of solution and form bubbles, which would cause it to shoot out the top of the tube, blasting water and gas more than 150 feet into the sky. Once it got started, the siphon effect would cause the reaction to continue indefinitely, or at least until the CO2 ran out. A prototype was installed and tested in 1995, and after it proved to be safe, a permanent tube was installed in 2001.” [“Lake Nyos–The Deadly Limnic Eruption“] According to the article (written in 2006), the tube is working but at least an additional five tubes are needed to reduce the levels of carbon dioxide to safe levels. A similar tube was installed in Lake Monoun in 2004, but an additional tube is also needed there. A quick search of the Web didn’t turn up any evidence that the additional tubes have been installed.

“Following the Lake Nyos tragedy, scientists investigated other African lakes to see if a similar phenomenon could happen elsewhere. Lake Kivu in Rwanda, [3,000] times larger than Lake Nyos, was also found to be supersaturated, and geologists found evidence for outgassing events around the lake about every thousand years.” [“Lake Nyos,” Wikipedia] Lake Kivu, unlike the other two exploding lakes, contains methane deposits as well as carbon dioxide deposits. These methane deposits can be exploited as fuel. According to Wikipedia, Lake Kivu contains “approximately 55 billion cubic metres (72 billion cubic yards) of dissolved methane gas at a depth of 300 metres (1,000 ft). Until 2004, extraction of the gas was done on a small scale, with the extracted gas being used to run boilers at a brewery, the Bralirwa brewery in Gisenyi.” The article went on to say:

“As far as large-scale exploitation of this resource is concerned, the Rwandan government is in negotiations with a number of parties to produce methane from the lake. Extraction is said to be cost-effective and simple because once the gas-rich water is pumped up, the dissolved gases (primarily carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulphide and methane) begin to bubble out as the water pressure gets lower. This project is expected to increase Rwanda’s energy generation capability by as much as 20 times and will enable Rwanda to sell electricity to neighboring African countries.”

I provide that background as segue to an article brought to my attention by its author, Ann Delphus, a reporter for Invention & Technology News. She apparently did a Web search that turned up a number of posts I have written about alternative energy, development, and Rwanda. She thought I might be interested in sharing an article she wrote that involves all of those subjects entitled “It’s Win-Win: Methane Pumped From African ‘Exploding’ Lake Will Fuel Electric Plant; Gas Removal May Avert Catastrophic Death Toll” [18 October 2010]. In her article, she writes:

“About two million people live in the valley surrounding beautiful Lake Kivu in east central Africa, and some of them – or all of them – could be killed by it almost instantly. That is the concern of some scientists who have studied Lake Kivu as well as two other lakes that have already experienced a gas eruption. Ironically, it is Lake Kivu’s deep-water reservoir of dissolved methane gas that will soon be the catalyst for positive change, as the big news in Rwanda now is that an American company, ContourGlobal, will soon be extracting 6.4 million standard cubic feet of methane per day from the lake to fuel an electrical plant it will build in the picturesque lakeshore town of Kibuye.”

To bring home how massive a tragedy a limnic explosion in Lake Kivu could be, Delphus notes that two million people represent “roughly the population of Kansas City and its suburbs or the entire Orlando metropolitan area.” She continues:

“Theoretically, if even half of the lake basin’s current population were to perish after a limnic eruption – one million people in the Lake Kivu basin instead of two million – it would rank in the top three most deadly natural disasters in all of recorded history, the other two being floods in China.”

Delphus goes on to discuss the work of Dr. George Kling of the University of Michigan, an expert on the exploding lakes. She continues:

“Since the Nyos eruption, Dr. Kling and other scientists have focused their attention on Lake Kivu, which … contains 350 times the amount of gas [found in Lake Nyos]. Scientists have estimated that the volume of gases has increased as much as 30 percent in just the past 30 years. Fossil evidence has revealed several incidences of massive biological extinctions in the course of thousands of years, leading scientists to believe that this has happened before and will happen again … unless, of course, mankind intercedes. That’s where New York-based ContourGlobal, its investment partner Reservoir Capital Group, and its engineering partner Antares Offshore come into the picture.”

Residents in the Lake Kivu area seem to have caught a break. Since the methane is exploitable, extracting it from the lake will reduce the risks of a limnic explosion while making a profit for ContourGlobal and its partners. Delphus explains how the deal was put together.

“ContourGlobal, through its new subsidiary, Kivuwatt Ltd., secured a 25-year agreement with the government of Rwanda to extract methane from Lake Kivu and to then sell the electricity it makes back to Rwanda’s power agency, Electrogaz. Phase one of the project – a floating barge, gas separation equipment, and a power plant – are now in the process of being assembled and [are] scheduled to be completed by this time next year. After approximately six months, ContourGlobal KivuWatt would most likely proceed with Phase two, the addition of three more gas extraction platforms to bring the electric power plant to its full capacity of 100 megawatts. Bill Fox, P.E., who is the project manager for KivuWatt, notes that it is the methane gas dissolved in the depths of the lake that is considered to be more unstable and therefore most troublesome with respect to preventing a lake turnover. The gas separation technology they will use is not new by any means – it is very similar to the process used in the oil and gas industry. However, it has been uniquely adapted for the proportions of methane and carbon dioxide that are dissolved in the depths of Lake Kivu.”

In past posts, I have noted that companies working in developing states need to be able to adapt to local conditions in order to succeed. That is apparently the business philosophy ContourGlobal uses in its emerging market work. Delphus explains:

“Mr. Fox describes ContourGlobal as an energy company that operates in niche markets, preferring projects with a favorable impact on the environment. The company looks to adapt technology for its own purposes, as it has done in working closely with engineers at Houston-based Antares Offshore, the company it hired to design the platform-based gas separation equipment for the Kivuwatt project. According to Mr. Fox, the barge and separation vessel will be moored 13 kilometers from shore, and, like an energy company that taps an underwater oil reservoir from a platform, what travels up the vertical pipe (called a riser) is a mixture of oil, natural gas, water, etc. The KivuWatt barge will have four risers produced of rigid, high density polyethylene (HDPE) that will reach a depth in the lake of 355 meters. Mr. Fox explains that the huge water pressure that deep in the lake will help propel the gas-laden water upward in the riser, and as the water travels upward, it will experience what he calls ‘gas lift’ as the methane and CO2 begin to be released from solution and will rush upward as a mixture of water and gas bubbles. The long, tubular separation vessel beneath the barge will work like a propane tank, he says, and the engineers who designed the setup have calculated that the de-gassification ‘sweet spot’ for the depth of the separation vessel is 20 meters below the barge and water surface. At that particular depth and pressure, there will be an optimization of the separation of methane and CO2 from the water. Between 75 and 85 percent of the methane will be released from the water and it will continue to rise up to where it will travel across to the power plant in one flexible reinforced thermoplastic pipeline (RTP). This horizontal pipeline will be suspended 10 meters below the water’s surface, tethered to the lakebed by concrete anchors and marked by buoys. The de-gassed water, carbon dioxide, and the significantly smaller amount of methane will be piped back downward to a depth of 240 meters and safely discharged in a stratum of the lake that sits above the deep, gas-laden resource zone.”

My suspicion is that ContourGlobal is returning the carbon dioxide into the lake in order to lower the greenhouse gas emissions of their project. A better solution, however, would be one in which the CO2 was put to some useful purpose while being rendered harmless. According to Delphus, that possibility still exists. She continues:

“According to Mr. Fox, Lake Kivu is a ‘slower-responding lake’ compared to the two lakes in Cameroon that experienced limnic eruptions in the 1980s. While KivaWatt’s phase one operation does not vent or disperse the accumulation of CO2 from Lake Kivu, he would not rule out the possibility that it could be a component of the second phase installation. Ideally, Mr. Fox would like to see the CO2 captured and put to some use.”

If contour global can figure out a way to make money capturing the CO2, it could prove to be a boon for Cameroon residents living near the other two exploding lakes. As noted above, they are still waiting for help in solving their gas build-up challenge. If ContourGlobal’s plans are fully implemented, the electricity produced will be a tremendous lift for the region’s economy. Even before the electricity starts flowing, however, the project has already had a positive economic impact. Delphus explains:

“Logistically, the barge itself is now being built at the shore by a prominent Kenyan civil engineering and transportation firm and is expected to be completed in April 2011. … KivuWatt is also carefully timing the completion of the electric power plant to coincide with the first gas arriving on shore to avoid unnecessary, duplicate plant startup costs. All together, this venture is projected to require an investment of up to $325 million. By some estimates, the methane resources could supply Rwanda’s energy needs for 400 years. Lake Kivu is, to a significant degree, a renewable resource. The carbon dioxide collects at the bottom of the lake as it bubbles up from molten rock deposits below the lake bed. Bacteria in the water convert the CO2 to methane.”

Before continuing, I must admit that Delphus’ description of how the methane is produced in Lake Kivu through microbial reduction of the volcanic CO2 started me wondering why bacteria couldn’t be introduced into the other two exploding lakes so that methane could be produced and exploited there. I’m sure that I’m not the first person to have wondered about this and my guess is that the process either takes a long time (i.e., too long to get a return on investment) or that environmental conditions are unsatisfactory for such a process to work. Delphus continues her discussion concerning Lake Kivu:

“The entire region is known as Africa’s Great Rift Valley, and it is a center of volcanic activity, including Mt.Nyiragongo near Goma, the capital of the North Kivu province (DRC). One British newspaper, in a feature story on Lake Kivu’s deadly gases, reported that a Swiss study found that the CO2 concentration in Lake Kivu rose 10 percent between 1974 and 2004, while the methane concentration rose 15 to 20 percent. Experts believe the methane created each year would fuel a 100-megawatt electrical plant. The capital investment in developing Lake Kivu as an energy source represents very good news for Rwanda, which has long been starved for energy. Even though only five percent of the population has electricity at this time, the country’s power provider, Electrogaz, can’t supply the full demand of 55 megawatts and must import about 13 percent of its electricity. When the full 100-megawatt capacity of the methane-fueled generators of KivuWatt are online, Rwanda expects to have a surplus of electrical power that it could export to neighboring Uganda. Plentiful, economical electricity is expected to not only fuel business and industry as well as raise the standard of living, it should prevent further deforestation of the land as people refrain from gathering wood to be used for fuel.”

In past posts concerning Rwanda, I have noted that the country’s president, Paul Kagame, is determined to move his country’s economy forward as quickly as possible. Although critics worry about the political climate Kagame has created, few of them doubt his sincerity about wanting his country to be prosperous and economically stable. Delphus concludes:

“Sub-Saharan Africa is, in general, an economically challenged part of the world. With the influx of investments of technology such as what has been developed by Antares Offshore on behalf of ContourGlobal, Rwanda may be just a couple of years away from beginning a societal transformation that access to affordable electrical power could produce. A venture like this is not without risks, however. Several projects have been initiated, but only one was operating last year. In 2008, another company’s platform sank just as it was ready to start production. Some scientists warn that tampering with the lake’s gases might in itself trigger a disaster. Mr. Fox notes that there have been volcanic eruptions with no adverse effects, and the engineering team worked diligently to meet all guidelines and to address any concerns. As for the opinion of the public of the construction of the methane equipment and the power plant, ‘they seem to be looking forward to it,’ says Mr. Fox. Indeed. Even the tourist reviews depict beautiful Rwanda in upbeat tones, calling it “brimming with optimism.”

To read more about the region, read my post entitled The Plight and Hope of East Africa. As most development analysts will tell you, access to reliable and affordable electrical power is absolutely essential for economic progress. If ContourGlobal is successful in its efforts, the new power plant will be a win for everybody in the region.