In the first of this two-part post [Is America Undergoing a Creativity Crisis? Part 1], I discussed an article by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman that reported the creativity quotient (CQ) of America’s children has started to decline for very first time — even as their IQs continue to rise. In the article, Bronson and Merryman discuss how creativity is tested. To get a taste of what those tests are like and how they are graded, click on the link to an 11-image tutorial entitled “How Creative Are You?” At the end of Part 1, I indicated that in Part 2 I would discuss some of the techniques that people have come up with to help us increase our natural creative capabilities.

For a lot of people, the first technique they think about when asked to generate ideas is brainstorming. Some analysts believe that brainstorming should be the last technique you think about not the first [“Forget Brainstorming,” by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman, Newsweek, 12 July 2010]. Bronson and Merryman explain why and then they offer some of the other techniques you can use to generate ideas. They begin:

“Brainstorming in a group became popular in 1953 with the publication of a business book, Applied Imagination. But it’s been proven not to work since 1958, when Yale researchers found that the technique actually reduced a team’s creative output: the same number of people generate more and better ideas separately than together. In fact, according to University of Oklahoma professor Michael Mumford, half of the commonly used techniques intended to spur creativity don’t work, or even have a negative impact. As for most commercially available creativity training, Mumford doesn’t mince words: it’s ‘garbage.’ Whether for adults or kids, the worst of these programs focus solely on imagination exercises, expression of feelings, or imagery. They pander to an easy, unchallenging notion that all you have to do is let your natural creativity out of its shell. However, there are some techniques that do boost the creative process.”

Before writing off brainstorming altogether, I’d like to discuss the challenges and benefits of the technique in a little more detail. In a previous post entitled Fostering Innovation, I wrote:

“Often creativity is a matter of technique. Once people are taught techniques that permit them to view challenges from different perspectives, they are surprised how creative they can be. This … is one of the reasons that brainstorming was invented. The belief was that more ideas could be generated by groups than by individuals because hearing others’ thinking would stimulate new thoughts in all participants. Studies have shown, however, that people brainstorming in isolation then coming together to discuss ideas produce more and better ideas than teams trying to brainstorm together from the start. There are several reasons for this. First, of course, is fear. People fear that others will think their ideas are stupid so they don’t bring them up. A second impediment to brainstorming, however, is even more significant. People have difficulty holding on to one thought (which they must wait to bring up in a group), while trying simultaneously to come up with other ideas. Individual brainstorming doesn’t suffer from this problem. People are simply able to move from idea to idea without having to wait.”

There are systems that permit individual brainstorming and group dynamics to be used together. When my colleagues Tom Barnett and Bradd Hayes were professors at the Naval War College, they worked in a department that used groupware to capture ideas and foster discussion. Groupware permits participants to brainstorm individually (writing down ideas as quickly as they are conceived) and permits them to see others’ ideas, which, in turn, can stimulate new thoughts as well. Groupware is not the end all and be all of creative thinking, but it has its place and has proved extremely useful when used to its full potential. One big caveat is that groupware, and the supporting IT equipment it requires, is not cheap and, therefore, not often available to most groups. Barnett and Hayes tell me that they were able to achieve similar results by using old fashioned pencil and paper. They simply had participants brainstorm individually and then hold a discussion using based on the lists that were generated. Bronson and Merryman discuss some other methods to foster creativity. They begin:

“Don’t tell someone to ‘be creative.’ Such an instruction may just cause people to freeze up. However, according to the University of Georgia’s Mark Runco, there is a suggestion that works: ‘Do something only you would come up with—that none of your friends or family would think of.’ When Runco gives this advice in experiments, he sees the number of creative responses double.”

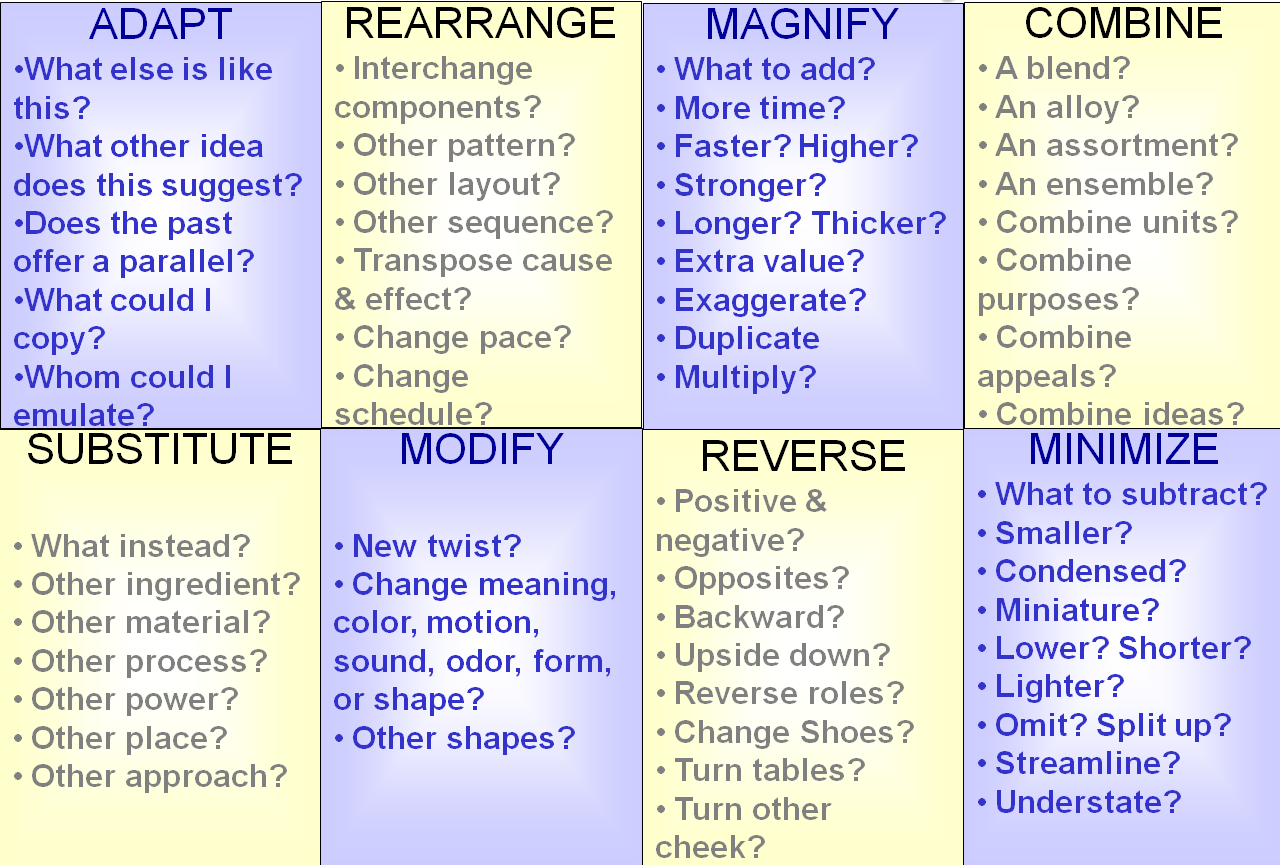

Everyone, no matter how dull, occasionally has a good idea. I’ve found that asking the right question is critical to getting a good answer. What separates great analysts from good analysts or great engineers and scientists from good engineers and scientists is the ability to ask the right question. If you find a good solution to the wrong question, you’re seldom better off than you were when you started. By looking at the challenge you are facing and then crafting the right questions about the problem, you’ll find that a lot of people can help you find creative solutions. Some analysts recommend asking “why” at least five times before accepting an answer. The idea is to keep peeling back answers until you uncover sufficient knowledge to understand the real problem. Other analysts believe there are six universal questions. They are: WHAT should be done? WHY is it necessary? WHERE should it be done? WHEN should it be done? WHO should do it? HOW should it be done? There are lots of other good questions to ask depending on the challenge you face. Some of those questions are summarized below:

Bronson and Merryman continue:

“Get moving. Almost every dimension of cognition improves from 30 minutes of aerobic exercise, and creativity is no exception. The type of exercise doesn’t matter, and the boost lasts for at least two hours afterward. However, there’s a catch: this is the case only for the physically fit. For those who rarely exercise, the fatigue from aerobic activity counteracts the short-term benefits.”

In other words, this suggestion should have been titled “Get fit, then Get Moving!” A number of executives, including the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, have installed stand-up desks in their offices so that they can work on their feet. Some of these desks even come equipped with treadmills. Bronson and Merryman move on:

“Take a break. Those who study multi-tasking report that you can’t work on two projects simultaneously, but the dynamic is different when you have more than one creative project to complete. In that situation, more projects get completed on time when you allow yourself to switch between them if solutions don’t come immediately. This corroborates surveys showing that professors who set papers aside to incubate ultimately publish more papers. Similarly, preeminent mathematicians usually work on more than one proof at a time.”

I’ve read that Isaac Azimov used to have a number of typewriters sitting around in a circle, each with a different project connected to it. When he moved to a different typewriter, his focus shifted to the project at hand. To read more about multitasking and what researchers are discovering, read my post entitled The Mind — it is a-changin’. The point being made by Bronson and Merryman is that your mind needs to time to mull over complicated challenges. So whether you take a break or sleep on it, the advice is good. Bronson and Merryman continue:

“Reduce screen time. According to University of Texas professor Elizabeth Vandewater, for every hour a kid regularly watches television, his overall time in creative activities—from fantasy play to arts projects—drops as much as 11 percent. With kids spending about three hours in front of televisions each day, that could be a one-third reduction in creative time—less time to develop a sense of creative self-efficacy through play.”

In Part 1 of this post, Bronson and Merryman lament the fact that since 1990 the average CQ of America’s children has been falling. Too much TV and video game playing are suspected to be at least partially to blame. The post mentioned above that discusses multitasking does point out children who play videogames develop some important talents (so I wouldn’t cut kids off completely from playing them); but, too much of anything is generally bad. Bronson and Merryman continue:

“Explore other cultures. Five experiments by Northwestern’s Adam Galinsky showed that those who have lived abroad outperform others on creativity tasks. Creativity is also higher on average for first- or second-generation immigrants and bilinguals. The theory is that cross-cultural experiences force people to adapt and be more flexible. Just studying another culture can help. In Galinsky’s lab, people were more creative after watching a slide show about China: a 45-minute session increased creativity scores for a week.”

I think this suggestion would have been better labeled “Diversify.” Not everyone can travel abroad or has an interest in culture — although I do believe that the enduring allure of National Geographic is that most of us are fascinated by how others live on this planet. Creativity gurus recommend reading magazines that are far afield from one’s normal activities. They recommend that you go see science fiction movies or attend the opera even if you don’t think you’d like them. Exposure to a variety of things that life has to offer opens up new avenues for creativity. Read biographies or autobiographies and then, when faced with a particularly troubling challenge, ask yourself how would a politician, an engineer, a musician, a philosopher, or a handyman attack the problem. If you can force yourself out of your normal perspective, you will see the challenge in a new light and new possibilities for solving it will emerge.

“Follow a passion. Rena Subotnik, a researcher with the American Psychological Association, has studied children’s progression into adult creative careers. Kids do best when they are allowed to develop deep passions and pursue them wholeheartedly—at the expense of well-roundedness. ‘Kids who have deep identification with a field have better discipline and handle setbacks better,’ she noted. By contrast, kids given superficial exposure to many activities don’t have the same centeredness to overcome periods of difficulty.”

I’m not sure how I feel about this suggestion. Passion is important, but for most people balance is also critical. Not everyone finds a vocation. Most people find jobs and some find careers. What I do agree with is that people who are passionate about what they are doing are more likely to dedicate the time and effort necessary to get things right. On the other hand, I know some very passionate golfers who aren’t very good — despite the hours they devote to the game. Some of the shots they must make are indeed creative; but it’s a creativity generated by necessity as a result of poor performance. The most important attribute of passionate people, I believe, is that they put ideas into action. That makes them more than dreamers. As well-known entrepreneur Richard Branson has been quoted as saying, “Screw it, let’s do it!” That’s passion. Bronson and Merryman continue:

“Ditch the suggestion box. If you want to increase innovation within an organization, one of the first things to do is tear out the suggestion box, advises Isaac Getz, professor at ESCP Europe Business School in Paris. Formalized suggestion protocols, whether a box on the wall, an e-mailed form, or an internal Web site, actually stifle innovation because employees feel that their ideas go into a black hole of bureaucracy. Instead, employees need to be able to put their own ideas into practice. One of the reasons that Toyota’s manufacturing plant in Georgetown, Ky., is so successful is that it implements up to 99 percent of employees’ ideas.”

We’ve all seen suggestion boxes in the past. How many of those suggestion boxes are simply places where dust settles? Most of them I’d bet. I really like the idea that “employees need to be able to put their own idea into practice.” Creative gurus have developed an almost endless list of techniques that can help people look at challenges in different ways. They have also developed systems that help people go from concept to implementation. As Professor Mumford insisted above, some of these techniques are garbage (he claims about half of them), but some of them are worth trying. I believe the single most important thing you can do to improve your creativity is learn how to ask good questions. The first thing you should question are assumptions. A lot of bad solutions have been recommended because they were based on faulty assumptions. Asking “why” is a good thing to do — not only for children, but for the rest of us as well.

Tomorrow I’ll conclude this series on creativity by focusing on an article that discusses the importance of imagination.