You may have heard the phrase “it’s a matter of taste.” Merriam-Webster offers the following example of its use in a sentence: “Some people like seafood and some people don’t. It’s all just a matter of taste.”[1] Sounds pretty straight forward; however, taste is a surprisingly complicated subject and seems to be getting more complicated. Just a few years ago, science only recognized four tastes. Here’s the 2013 Cliff Notes version of the topic:

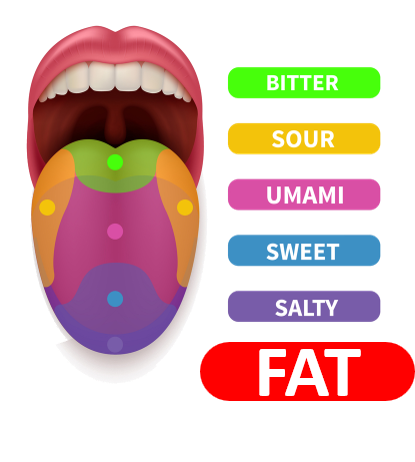

“The stimuli for taste are chemical substances dissolved in water or other fluids. Taste can be described as four basic sensations, sweet, sour, salty, and bitter, which can be combined in various ways to make all other taste sensations. Taste receptors (called taste buds) for these sensations are located primarily on various areas of the tongue: front, sweet; sides, sour; sides and front, salty; and back, bitter. There are about 10,000 taste buds, which are situated primarily in or around the bumps (papillae) on the tongue. Each papilla contains several taste buds, from which information is sent by afferent nerves to the thalamus and, ultimately, to areas in the cortex.”[2]

The Cliff Notes staff was reporting on two thousand years of accepted theory. Reporter Robert Krulwich (@rkrulwich) explains, the Greek philosopher Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BCE) defined the original four tastes claiming “that when you chew on your food and it crumbles into little bits, those bits eventually break into four basic shapes.”[3] He continues, “When something tastes sweet, [Democritus] said, it is because the bits are ’round and large in their atoms.’ Salty is isosceles triangle bits on your tongue, Bitter is ‘spherical, smooth, scalene and small,’ while sour is ‘large in its atoms, but rough, angular and not spherical.’ And that’s it, said Democritus. Everything we taste is some combination of those four ingredients.”

According to Krulwich, the “shape of tastes” theory made sense to Plato and Aristotle and those were two historical heavy hitters. As a result, Krulwich notes, “Pretty much ever since even modern scientists have said that’s the number: four.” Surprisingly, Krulwich reports, “When taste buds were discovered in the 19th century, tongue cells under a microscope looked like little keyholes into which bits of food might fit, and the idea persisted that there were four different keyhole shapes.” Score one for Democritus — even if he was wrong.

Before discussing how science is complicating the topic of taste, I want introduce a little more precision to the terms “flavor” and “taste.” A lot of people use the terms “taste” and “flavor” interchangeably — and that is unlikely to change; however, tastes have a biologic basis. To determine whether something is really a “taste,” researchers have to isolate the sense of taste from other senses, especially the sense of smell. Jenn Savedge explains, “When researchers talk about taste, they’re talking about something that can be perceived with the tongue alone. Close your eyes and plug your nose and you will recognize salt if it is sprinkled on your tongue.”[4] In other words, when you think about taste think tongue. When you think about flavor, think about all of your sensory organs — but, especially your tongue and your nose.

The Sense of Taste Gets Complicated

A few years back, a fifth “taste” was finally accepted by the scientific world — Umami, a Japanese word that roughly translates to “savory.” Umami was recognized as the scientific term to describe the taste of glutamates and nucleotides back in 1985 at the first Umami International Symposium in Hawaii; however, the term only achieved general recognition as a fifth taste in the last decade. “When it comes to flavor,” writes Melinda Johnson (@MelindaRD), a Clinical Assistant Professor for the Nutrition Program at Arizona State University, “umami is the shady character hiding in the dark corner. While the other tastes — sweet, salty, sour and bitter — all have an easily identified punch that’s delivered upfront, umami prefers subtlety and nuance. It is the mystery man of flavor profiles, adding a richness and depth that can only be summed up as je ne sais quoi.”[5] To learn more about the long struggle to get umami recognized as a taste, read my article entitled The Taste of Umami.

More recently, scientists have begun touting a sixth taste — fat. In an experiment conducted by researchers at Purdue University, participants were placed in a specially lit room and given “nose clips so they couldn’t mistake the aroma of food for taste and then had them try different concentrated samples and sort them by taste including sweet, salty, sour, bitter and blank. In the study 64% of participants could distinguish a fatty acid sample from the group. While a fatty food taste test may seem to have been a dream come true, subjects reported samples with shorter fatty acid chains tasted sour and with longer fatty acid chains tasted pungent or irritating.”[6] Professor Richard Mattes, who has been working on this challenge for years, noted, “At high concentrations, the signal [a fatty acid] generates would dissuade the eating of rancid foods.”[7] Professor Mattes’ team was trying to determine, once and for all, whether fat was a taste like salty, bitter, sweet, sour, and umami. Since the term “fat” doesn’t sound very scientific, researchers are using the term “oleogustus.” Kathy A. Svitil reports that Mattes isn’t the only researcher seeking to answer the question of whether fat is a taste. She writes, “No matter how cleverly prepared, fat-free foods never seem satisfying. Now we know why. Nutritionist Philippe Besnard of the University of Burgundy in France has found that the 10,000 taste buds on the tongue seem to include a type that specifically responds to the flavor of fat.”[8]

Research by the Japanese Ajinomoto Group is now exploring a flavor enhancer closely related to umami — kokumi, a “sensory phenomenon with the potential to redefine deliciousness.”[9] Kokumi relates to umami in a number of ways. The Japanese scientist credited with the discovery of umami was the late Dr. Kikunae Ikeda. His research also led to the creation of “monosodium glutamate — aka MSG. [In 1909], the Ajinomoto Group was founded, patenting MSG as AJI-NO-MOTO™, the world’s first umami seasoning.” According to Dr. Joe Formanek, director of ingredient innovation at Ajinomoto Health & Nutrition North America, Inc., the company “helped fund the research that led scientists to locate dedicated umami receptors on taste buds in 2002, further validating that umami is a basic taste.” As for kokumi — literally “rich taste” in Japanese — the jury is still out about its place in the culinary lexicon.

Ajinomoto scientists began investigating kokumi in the 1980s — trying to discover where it comes from and how to re-create it. Formanek notes that umami creates a savory, almost meaty profile whereas kokumi creates “a sense of richness, body and complexity not unlike what develops in aged wine and cheese, or a long-simmered stock.” Ajinomoto scientists are pretty sure kokumi is not a new basic taste. “Compounds that generate kokumi have no taste of their own; rather, they amplify a food’s umami, salty and sweet tastes, even creating a sense of filling the mouth fully — a quality called ‘mouthfulness.’ … The upshot: ‘Kokumi works with other flavors and tastes to enhance the character already present in food,’ Formanek said.”

Concluding Thoughts

The enjoyment of food relies on how all our senses perceive them — not just how our tongues perceive basic tastes. As more is learned about these relationships, cognitive technologies will be useful in helping the food industry combine sensory characteristics — including kokumi — in an appealing way. To some extent, the Enterra® SensoryPrint™ technology can already do this for flavors. Eventually, sights, smells, and textures should be able to be added to the mix. The result should be a more pleasurable dining experience for everyone.

Footnotes

[1] Staff, “a matter of taste,” Merriam-Webster.

[2] Staff, “The Chemical Senses: Taste and Smell,” CliffsNotes.com, 26 April 2013.

[3] Robert Krulwich, “Sweet, Sour, Salty, Bitter … and Umami,” by National Public Radio, 5 November 2007.

[4] Jenn Savedge, “Can you taste fat?” Mother Nature Network, 22 July 2015.

[5] Melinda Johnson, “3 Reasons to Get a Little More Umami in Your Diet,” >U.S. News & World Report, 9 October 2015.

[6] Gillian Mohney, “Sweet, Salty and Now Fatty: Scientists Work to Uncover ‘Sixth’ Taste,” ABC News, 21 July 2015.

[7] Vanessa Coleman, “Scientists discover the taste of fat, and it’s not good,” Junior College, 23 July 2015.

[8] Kathy A. Svitil, “Why Fat Tastes So Good,” Discover Magazine, February 2006.

[9] Ajinomoto Group, “Tracing the sensory story from umami to kokumi,” Food Dive, 2 August 2021.