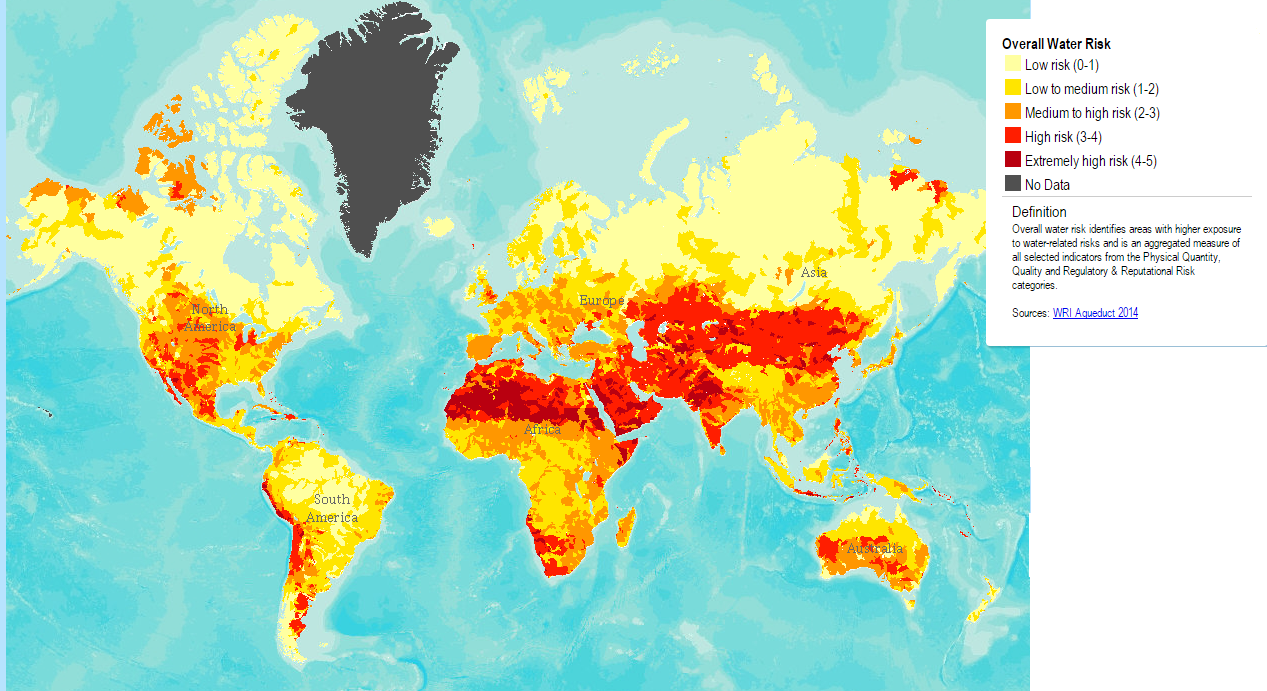

“The world runs on water,” writes Betsy Otto, Director of the Global Water Program at the World Resources Institute (WRI). “Clean, reliable water supplies are vital for industry, agriculture, and energy production. Every community and ecosystem on Earth depends on water for sanitation, hygiene, and daily survival. … More than a billion people currently live in water-scarce regions, and as many as 3.5 billion could experience water scarcity by 2025.”[1] A briefing prepared by analysts at Stratfor notes, “Water is essential for: Manufacturing; agriculture; commerce; many types of energy; economies; and, the existence of human and other life forms.”[2] The briefing goes on to note, “One thing water can never be: Manufactured.” WRI produced a detailed map depicting areas with higher exposure to water-related risks.

The Stratfor briefing notes, “When areas are under water stress, effects can include: Reduced food and livestock production; population movements; additional costs of living; famine/starvation; political stress; and other problems.” Although this article primarily focuses on the difficulty many people living at the base of the pyramid have obtaining water, water scarcity is not just a challenge for the developing world. Christopher Gasson, publisher of Global Water Intelligence, told Pilita Clark (@pilitaclark), “The marginal cost of water is rising around the world. Previously, water was treated as a free raw material. Now, companies are realising it can damage their brand, their credibility, their credit rating and their insurance costs. That applies to a computer chipmaker and a food company as much as a power generator or a petrochemicals company.”[3] Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, chairman of Nestlé, told Clark, “Water scarcity is a far more pressing problem than climate change, but receives much less political attention than it should.” Although companies obviously have a vested interest in water availability, Clark notes, “The solution to water scarcity is largely in the hands of governments, not companies, because it requires policies such as better regulation of irrigation groundwater or more intelligent use of wastewater.” Clearly, managing scarce water resources is a big challenge; but, big data analytics can help. Ben Ward writes, “Big data has been around for years, but typically was well structured and organised. The data being generated today comes from a variety of sources, in multiple formats, of varying quality and at varying times, all of which poses challenges to the water industry as to how best to use it.”[4] He continues:

“Significant headway is being made here, although the true challenge for the water industry is how this information is shared with other decision makers, such as local authorities, the Environment Agency and private developers, to ensure that maximum value is obtained for every pound spent by delivering co-ordinated investments. … If water companies can harness the power of enterprise geographic information systems, capitalise on mobile technology and deploy the latest computing technologies needed to crunch through the big data, they will be in a strong position to deliver personalised services to cater for customers’ individual needs.”

Implementing solutions that involve big data and artificial intelligence are great for areas that have water systems, but they don’t offer much help to people living at the base of the pyramid in areas with little or no infrastructure. Often a simple technology offers a better solution to an urgent challenge than advanced technology. Water retrieval is one of those cases. Cynthia Koenig, CEO of Wello, notes, “The time, physical and health burdens of water collection trap families in a vicious cycle of poverty.” Her company manufactures a product called the WaterWheel, which “is a simple, effective tool designed for people who lack reliable access to safe water.” The following video, produced by Wello, highlights the challenge and how the WaterWheel meets the challenge.

As the video points out, Wello sells the WaterWheel to families that can afford one. However, many people living at the base of the pyramid can’t afford to pay even the modest price of the WaterWheel, which is around $50. You can help struggling families by donating one or more WaterWheels through Wello, which is a 501c3 non-profit organization. Just click on this link. Madhukar Dhas, Director of Dilasa Sanstha (an NGO focused on creating infrastructure for sustaining livelihoods of marginalized communities), asserts, “The WaterWheel is beneficial on so many levels; reducing the drudgery of water collection for women, providing irrigation for household vegetable gardens, and enabling people to use their time more productively.”

Although the WaterWheel addresses one challenge facing people living at the base of the pyramid, it can only move water when water is available. Water scarcity is becoming a big challenge — one the world needs to address. A few years ago, David Biello (@dbiello), science curator at TED Talks, wrote about a report published by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). He summed up the report this way: “The rich play with fire and the poor get burned.”[5] He notes that water scarcity will “afflict the poorest the most, particularly subsistence farmers throughout the world who depend on consistent rains for adequate food.” The developed world needs collectively to use its resources to address the water scarcity challenge. Like Ward, Biello believes that big data analytics can help. He writes, “Continuing to improve the data about impacts [of climate change] is an ongoing challenge for the scientific community.” WRI’s Betsy Otto is also a big supporter of using advanced analytics to address the water scarcity challenge. She told Ariel Schwartz (@arielhs), a Senior Editor at Co.Exist, “When thinking about resilience in the face of risk, it’s not just baseline stress, but what the disruptions are that could really wreak havoc.”[6] Schwartz reports, “Otto discovered a number of striking things while putting together the map. Places that haven’t traditionally had high water risks — the East Coast of the United States, the upper Midwest, Europe — now have medium to high water risk. This is because of changes in water demand, withdrawal patterns, weather, and water-supply patterns. At the same time, places where there’s already high competition for water (i.e., India) are at serious risk when combined with annual variability in water.” As Biello notes, dealing with water scarcity is going to be one of the defining challenges of the 21st century.

Footnotes

[1] Betsy Otto, “Water,” World Resources Institute.

[2] “Water Scarcity: Examining Impacts Around the World,” Stratfor.

[3] Pilita Clark, “A world without water,” Financial Times, 14 July 2014.

[4] Ben Ward, “Water: Big data and artificial intelligence,” New Civil Engineer, 24 September 2014.

[5] David Biello, “Food and Water Shortages May Prove Major Risks of Climate Change,” Scientific American, 30 March 2014.

[6] Ariel Schwartz, “An Incredibly Detailed Map Shows The Potential Of Global Water Risks,” Fast Company, 13 November 2014.