At the end of a previous post entitled “Resilience in the Food Supply Chain,” I indicated that I would write a follow-on article discussing current risk management efforts in the food supply chain focused on mitigating the impact of climate change and providing manufacturers with upstream visibility into their food supply chains. An article published on The Dairy Site states, “Traditional pressures on the food and agri industry (supply and demand dynamics, a burgeoning population and rising agri commodity prices) are being compounded by a new set of external influences.” [“Transforming Food and Agri Supply Chain,” 18 February 2013] The article goes on to list a few of those external influences:

“The direct use of agri commodities for biofuel production and an increased awareness of the energy intensity of food production, for example, have embroiled food and agri companies in an ongoing food vs. fuel debate. Similarly, speculation in agri commodity markets and the regulatory responses this has triggered from governments worldwide, has added to the complexity of the environment in which the sector operates.”

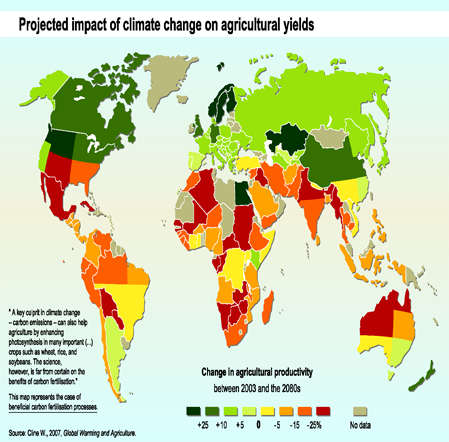

To that list you can add water usage in agriculture and changing climate patterns. Eric Lamphier asserts that the food supply chain “comes with layer upon layer of complexity.” [“Guest Commentary: Achieving Agility in the Food Supply Chain,” Logistics Viewpoints, 24 January 2013] All of those external influences and complexities bring with them risks that make the food supply chain vulnerable to disruption. The attached map shows the projected impact of climate change on agricultural yields (click to enlarge). Additionally, Ambassador Ertharin Cousin, Jose Graziano da Silva, and Dr. Kanayo F. Nwanze, insist, “We are at a tipping point in the fight against hunger and malnutrition. The world is becoming a less predictable and more threatening place for the poorest and most vulnerable.” [“Principles and Practice for Resilience, Food Security and Nutrition,” Huffington Post The Blog, 25 January 2013] If there is one sector in which the world needs more predictability, it’s the agricultural sector. Predictability is the essence of food security.

In the abstract for an article published in the journal Science, Tim Wheeler and Joachim von Braun, write, “Climate change could potentially interrupt progress toward a world without hunger. A robust and coherent global pattern is discernible of the impacts of climate change on crop productivity that could have consequences for food availability.” [“Climate Change Impacts on Global Food Security,” 2 August 2013] The abstract continues:

“The stability of whole food systems may be at risk under climate change because of short-term variability in supply. However, the potential impact is less clear at regional scales, but it is likely that climate variability and change will exacerbate food insecurity in areas currently vulnerable to hunger and undernutrition. Likewise, it can be anticipated that food access and utilization will be affected indirectly via collateral effects on household and individual incomes, and food utilization could be impaired by loss of access to drinking water and damage to health. The evidence supports the need for considerable investment in adaptation and mitigation actions toward a ‘climate-smart food system’ that is more resilient to climate change influences on food security.”

The term “climate-smart food system” implies that Big Data is going to play a significant role in helping to manage agricultural production. Most “smart” systems discussed today are smart because they draw insights from Big Data analytics. Jim Langcuster writes, “If you haven’t yet heard [the term Big Data] dropped in casual conversation with other farmers, you likely will — soon.” [“‘Big data’ will change the way you farm,” Southeast Farm Press, 28 August 2013] Langcuster reports that two Auburn University researchers, John P. Fulton, a professor of biosystems engineering, and Simerjeet Virk, a biosystems research engineer, along with Andrew Williamson, a British cereal crops producer and Nuffield Farming Scholar, are promoters of Big Data in agriculture. They “contend that data compiled in real time are already providing producers with a clearer, more comprehensive picture of all facets of farming, whether this happens to be soil science, seed rates, fertilizer optimization or weed and pest control. They predict that this growing body of data will ultimately free producers of much of the day-to-day guesswork associated with farming.” In other words, Big Data analytics should help provide some of the desired predictability required to make the food supply chain more secure. Langcuster notes that the three scholars “have identified seven major lessons farmers should draw from this Big Data revolution.” The first lesson is that Big Data helps farmers see the big picture.

“Big data will secure a considerably clearer farming picture. Virk says that the kind of refined farming pictures … farmers around the world are compiling on the basis of farming data are destined to become even clearer in the future — not only clearer but better integrated. ‘The next step will be a cloud-based system that integrates all facets of farming on behalf of producers,’ he says.”

Although food security will ultimately be obtained farm by farm, it is important for agricultural professionals to understand the big picture, see trends, gain insights, and implement appropriate strategies in response. The second lesson concerns diversity.

“Along with clarity comes diversity. ‘The farming picture will not only become more refined but also more diverse,’ says Fulton, who draws a comparison with the different ways individual homeowners manage their landscapes.”

As I noted in the post discussed at the beginning of this article, corn, wheat, and rice now supply most of humanity’s calories. That lack of the diversity has a number of analysts concerned. As farmers learn what kinds of crops grow best in their given circumstances, they may come to appreciate the value of crop diversity. The next lesson deals with data storage.

“Big data should be viewed as stored knowledge for lean times. As Williamson sees it, his job as a farmer is to ‘convert energy generated by the sun into profitable crops.’ In a sense, a farming data stream should be viewed much the same way: As stored knowledge that can provide farmers with a clear, comprehensive picture of their farming operations — an especially valuable asset during down cycles, he says.”

Albert Einstein has been credited with defining insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” A farmer who continues to plant the same crops, even when conditions change, may not be insane; but, he’s also not very smart. By having a trove of stored knowledge, farmers will be able to do something different during difficult times thereby achieving better results. The next lesson has to do with intuition.

“Big data is no substitute for farmer’s intuition. Despite the promise of Big Data, Fulton stresses that the ‘number 1 data set will always be a farmer’s intuition.’ ‘There is no data more valuable than the insights a farmer has gained over 10, 20 or 30 years of experience,’ he says. ‘The promise of big data will come from overlaying it with all the insights a farmer has gained through years of experience. Virk shares this view. In the end, farmers will always know more about their farming operations’ strengths and weaknesses than any software or machine, he says.”

In the past, I have stressed that the objective of Big Data analytics is help decision makers reach better decisions. Big Data analytics systems are not intended to replace decision makers altogether. The fact that some farmers have been doing things the same way for decades does require a shift in their thinking when they digitize their operation. That is exactly what the next lesson states.

“Big data requires a mindset change. Farmers are creatures of habit, Williamson says. Most think that time spent in the field is more valuable than time invested peering into a computer screen. Experience has taught him that time invested analyzing his farm data is just as important as time spent in the field. Indeed, producers who opt to manage their own data rather than pay an analyst to do it should develop a new daily routine, he says. ‘If you’re going to do it yourself, you had better be comfortable with spending more time on the computer,’ he says.”

The next lesson discusses the important role that Big Data analytics will play in feeding the world.

“Big Data will play a critical role in feeding the world. Big data is gaining traction at an especially critical time in history as farmers gear up to feed an estimated 9 billion people by midcentury. ‘This will require farmers to secure higher levels of production efficiency, and this can only be attained with more mechanization and other forms of technological adoption,’ Fulton says. Big data will fill much of this void by providing producers with a clearer understanding of how to match varieties to soil and climatic conditions along with strategies for reducing fertilizer, pesticide and herbicide applications, all with the aim of securing the highest levels of farming efficiency, he says.”

Even small subsistence farmers, many of whom do or will own smartphones, will have access to data that will help them become more productive — even if they can’t afford many of the technologies that will drive large agricultural enterprises. Molly E. Brown and Christopher C. Funk note, “The very low agriculture productivity of food-insecure countries presents a great opportunity. Transform these agricultural systems through improved seed, fertilizer, land use, and governance, and food security may be attained by all.” [“Food Security Under Climate Change,” NASA Publications, 1 February 2008] The final involves the inevitably of Big Data analytics in agriculture.

“Like it or not, big data is the new reality in farming. While farmers will have some choices about how to participate in the coming big data revolution, they cannot afford the luxury of not participating, Fulton says. ‘We’re already seeing new partnerships growing out of these changes at a steadily accelerating pace, and to be successful, farmers will need to be engaged with these emerging partnerships,’ he says. ‘But it’s important that they ask the right questions before joining these partnerships and only partner with people and organizations that they trust.'”

As a concluding note, analysts remind us that the agricultural sector is not only affected by climate change but that agricultural activities affect the environment. Big Data has a role to play here as well. Suzy Friedman writes, “By gathering and using more data about the nutrient needs of their own fields, for example, farmers can become much more efficient in applying fertilizer, reducing what is lost to water or air and saving themselves money. This benefits all of us, because nutrients that are not taken up by crops can lead to water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, once they have detailed information about how water moves across and through the agricultural landscape, farmers and watershed managers can be much smarter about where to put filters such as buffers and wetlands that capture nutrients that run off fields. This, in turn, improves water quality in the streams, rivers and lakes that the nutrients otherwise would wash into.” [“Farmers embrace Big Data to reduce pollution,” Greenbiz.com, 4 October 2013] Given all of the evidence, it’s hard to disagree with Fulton’s, Virk’s, and Williamson’s final conclusion that “like it or not, big data is the new reality in farming.”