Over the last several decades fat in our diets has received a lot of bad press. Low fat and no fat foods now fill supermarket shelves and are highlighted on restaurant menus. New evidence, however, indicates that some guidelines may have led us astray. Writing about British medical guidelines, Jenny Hope reports, “Guidelines that told millions of people to avoid butter and full-fat milk should never have been introduced, say experts. The startling assertion challenges advice that has been followed by the medical profession for 30 years. The experts say the advice from 1983, aimed at reducing deaths from heart disease, lacked any solid trial evidence to back it up.”[1] Hope notes that similar guidelines had been introduced in America half a dozen years earlier. She continues:

“The researchers carried out a review of data from trials that would have been available to UK and US regulators at the time. These trials were regarded as the ‘gold standard’ of medical testing. Six relevant trials were found, spanning an average of five years, and involving 2,467 men — most of whom had survived a heart attack or similar event. The trials looked at the relationship between dietary fat, cholesterol, and coronary heart disease. The review found no difference in heart deaths, regardless of whether people were on a high fat or lower fat diet. Professor Iain Broom, of the Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, said there was now mounting evidence against the introduction of low-fat diets to combat heart disease.”

Dr. Donald B. Jump, Professor of Nutrition and Exercise Sciences at Oregon State University, states, “Dietary fat plays several key roles in our physiology and well-being.”[2] He continues:

“It provides flavor to food. Ingestion of fat is important for the intestinal absorption of lipid-soluble vitamins like vitamins A, D, E, and K. Fat is a key source of metabolic energy. Components of fat are also important building blocks of all cells in the body. Fat, in the form of glycero- and sphingolipids, makes up the bulk of cellular membranes. These complex lipids are composed of fatty acids bound to glycerophosphate or sphingosine. Cellular membranes serve as barriers between compartments, such as the inside and outside of the cells, and are important for the maintenance of cellular structural integrity. They also play important roles in metabolism and in the regulation of cell function. Fatty acids also function as signaling molecules, thereby regulating cell function.”

Before you rush out and start gorging on fatty foods, Professor Jump cautions, “The type and quantity of fat ingested affects our health. Health problems arise when we ingest too much fat or the wrong type of fat.” He notes, “There are four kinds of fat: saturated, trans, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fat.” Most physicians and scientists still recommend that you get most of your dietary fat from foods that provide unsaturated fats (such as, olive oil, avocados, nuts, and canola oil). Dr. Diane H. Morris (@Moorgate1812), writes, “In the drive to get fat out, an important message has been lost — some fat is needed in the diet for good health.”[3] Felicia Stoler (@feliciastoler), a registered dietitian, told April Daniels Hussar (@aprilhussar) that your body will let you know when you are not ingesting enough fat.[4] “There is no ONE telltale sign,” Stoler told Hussar; “rather, it’s cumulative. In other words, though some of the following signs could have other causes, taken in combination, they could add up to a warning.” The five potential signs that you may not be getting enough fat in your diet include: Hunger, dry skin, poor body temperature regulation, extreme mental fatigue, and, in women, loss of your menstrual cycle.

Most of us probably don’t have a problem eating enough fat. After all, fat adds flavor. As Dr. Morris writes, “In foods, fat carries flavors and promotes tenderness.” We’ve all tasted low-fat or no-fat foods that are about as appetizing as cardboard. Restaurants and fast food chains certainly understand this. Julie Jargon (@juliejargon) reports, “Food and restaurant companies are under increasing pressure to make products healthier, but sometimes they don’t want customers to know when they have cut the salt or fat.”[5] She explains:

“It might seem like food companies would want to trumpet their health initiatives as much as possible. Many times they do, but companies are often cautious because altering the recipe of a successful product to cut salt, sugar, fat or other ingredients risks changing flavor and texture. And consumers don’t always react with their pocketbooks the way the clamor for better nutrition might suggest.”

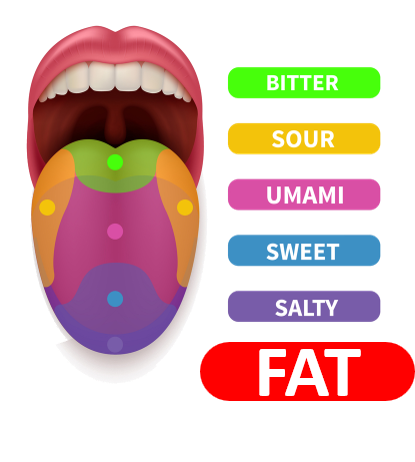

In addition to reevaluating recommendations about the ingestion of fat, some scientists are reevaluating whether or not fat represents a sixth basic taste. For thousands of years our sense of taste was thought to be made of four primary tastes: Sweet, bitter, salty and sour. About hundred years ago, a Japanese scientist named Kikunae Ikeda proved there was a fifth basic taste he called “umami,” which roughly translates to “savory.” However, it has only been the last ten years or so that umami has been universally recognized as a basic taste. For more information about umami, read my article entitled “The Taste of Umami.”

According to Richard Cornish (@FoodCornish), an Australian scientist named Russell Keast is the researcher pushing the idea that fat is actually a sixth basic taste.[6] Cornish elaborates:

“Fat is the sixth taste. That’s the message explored in a landmark paper just published by a Melbourne scientist that could change obesity treatment, food production and our relationship with food forever. Professor Russell Keast, head of the Centre for Advanced Sensory Science at Deakin University, last week published a peer reviewed paper in the journal Flavour. In it he proves and explores our tongue’s ability to detect fat as a distinct taste similar to our ability to sense sweet, sour, bitter, acid and savoury. After half a decade’s research and subjecting 500 volunteers to taste trials Professor Keast proved the human tongue had taste buds that could detect the presence of fatty acids at levels as low as 10 parts per million. … The paper suggests that people who detect fatty acids also associate the taste sensation with the feeling of being full and that people who have difficulty in detecting fatty acids are often obese. … ‘These findings could lead to the food industry responding with new products that reintegrate naturally occurring fatty acids to help people feel full,’ says Professor Keast.”

If Professor Keast is correct, it could certainly go a long ways towards explaining why fat makes foods so much more flavorful for most people. “Whether the scientific world accepts fat as a ‘taste’ like sugar, which gives us a pleasant sensation,” Keast said, “will become a matter of academic debate. But I am positive that we will now see a change in the way we view and perceive fat.” Based on Professor Ikeda’s experience, it may take a long time indeed for the world to recognize fat as a basic taste; nevertheless, people will continue to enjoy the taste and benefits of the right kind of fat.

Footnotes

[1] Jenny Hope, “Butter ISN’T bad for you after all: Major study says 80s advice on dairy fats was flawed,” Daily Mail, 9 February 2015.

[2] Donald B. Jump, “What’s Good about Dietary Fat?” Linus Pauling Institute, June 2008.

[3] Diane H. Morris, “Six Reasons to Put a Little Fat in Your Diet,” CanolaInfo, 2007.

[4] Felicia Stoler, “5 Signs That You Don’t Have Enough Fat in Your Diet,” Self, 15 May 2012.

[5] Julie Jargon, “Less Salt, Same Taste? Food Companies Quietly Change Recipes,” The Wall Street Journal, 23 June 2014.

[6] Richard Cornish, “Scientists find fat may be the sixth taste,” goodfood, 9 February 2015.