Last February Tim Burt reported that “the Baltic Dry Index, a benchmark that measures the price paid for shipping dry goods, such as iron ore and corn around the world plunged to a 25 year low. For those with high shipping costs this will come as good news but for shipping organisations this spells trouble and a leap to cost-saving methods. But maybe it’s time for a re-think.” [“Slow ships and the wages of volatility on supply chains,” Procurement Leaders, 2 February 2012] Burt continues:

“The Baltic Dry Index tracks worldwide, international shipping prices, taking into account 26 shipping routes and covers Handymax, Panamax and Capesize ships and has been traditionally seen as an indicator into the state of global trade. The index crashed in 2008 before commodity prices peaked and then bounced back before commodities rose later that same year.”

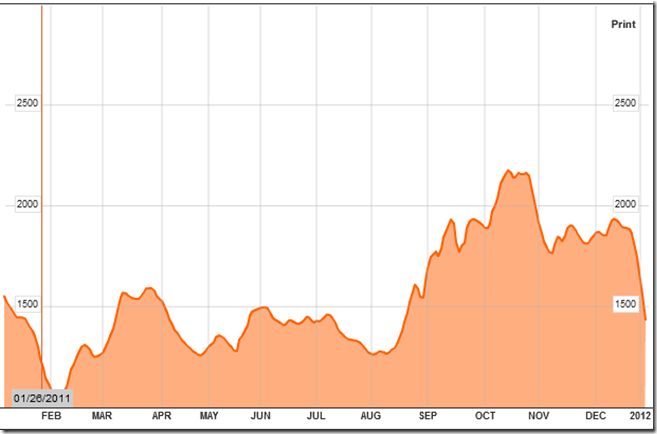

Chris Jacob Abraham, a Senior Consultant with IBM, agrees with Burt that Baltic Dry Index (BDI) has been a fairly accurate predictor of economic growth. That’s he was concerned about what the BDI was telling him we headed into 2012. [“A puzzling and precipitous divergence,” @ Supply Chain Management, 9 January 2012] Below is a graph of how the BDI tracked over 2011 — note the drop in the Index that Burt reported as 2012 began.

Burt notes, “The index recently slumped to 662, its lowest level for 25 years because of a number of factors, … including poor weather in Australia and Brazil, the early Chinese New Year and the sheer increase in the size of ships. These influences have led to reduced stock levels, closed factories and provided excess space on ships all of which have reduced demand.” He continues:

“Interestingly and very much linked to this is the fact that shipping companies are ordering ships to slow down in an attempt to cut costs because of such a slump in demand. A report on Bloomberg found that ships have slowed by 11% since last August with A.P Moeller Maersk cutting the speed f its fleet to 17 knots from 20 knots in 2008. Morton Engelstoft, COO of the shipping giant, told Bloomberg that ‘There is still some potential for slow-steaming, both for us and probably for the industry.’ ‘We are looking into the possibility of super slow-steaming. That would be 12-16 knots,’ he added. What is obvious, but interesting none-the-less, is how a cost saving for one represents a cost increase for another. For those using the shipping services, there can’t be much advantage in slow steaming, so maybe this is one of those occasions where procurement needs to reach out to suppliers of shipping services and come to an arrangement that can mitigate the risk to both parties. Certainly there’s a case for collaboration here.”

Most analysts appear to agree that an excessive over-capacity of dry bulk ships is what has created the crisis in that sector. As a result, the BDI is no longer an accurate barometer for the economy. In an effort to decrease capacity (and, thus, increase rates), companies are scrapping ships. The Financial Times reports that more tonnage was demolished in 2011 than in the previous eight years combined. [“Dry-bulk shipping,” by the Lex Team, 5 October 2011] The article indicates that the scrapping orgy could continue this year to offset more new ship deliveries “than they know what to do with.” The article continues:

“This is what happens when an industry takes collective leave of its senses. For much of the early part of the past decade, dry-bulk order books bore an identifiable relationship to real demand. But as credit flowed more freely and faith in the commodities ‘supercycle’ grew stronger, orders piled in, many of them to a new breed of state-backed Chinese shipyard. So undiscriminating was this wave of cash, in fact, that China’s total shipbuilding market share edged ahead of Korea’s – the first time that such a change had happened without some kind of technological stimulus. Orders had migrated from Europe to postwar Japan as welding replaced riveting, for example, then from Japan to Korea as floating docks replaced land-based yards. All China offered was speed, capacity and cheap, pliant labor. Restoring sanity will take time.”

Apparently China’s leaders were listening. A month later, Robert Wright reported, “Li Shenglin, China’s transport minister, has pledged to slow deliveries from the country’s shipyards, in a sign that the world’s biggest shipbuilding nation will confront the oversupply problems that have created the worst crisis to hit the industry in decades.” [“China vows to turn tide on flood of ships,” Financial Times, 3 November 2011] Wright continued:

“Rates in nearly all shipping sectors are too low to cover costs, as deliveries of ships ordered before the 2008 crisis expand capacity far faster than demand. At the same time, shipping companies are having to absorb fuel prices pushed sharply higher by rising oil prices. The crisis has been most acute for oil tanker operators, but has also hit container shipping companies and operators of ships carrying dry bulk commodities such as coal and iron ore. It is expected to persist for longer than the slump in late 2008 and 2009 because demand is likely to take so long to absorb the excess ships. China would use ‘every possible means’ to alleviate shipping overcapacity, Mr Li said, without saying what measures the government planned to take. It remains to be seen whether the government succeeds in persuading shipyards to do as it wants.”

As the New Year began, the crisis continued. In January, 2012, Keith Bradsher reported, “As recently as six weeks ago large freighters that can carry bulk commodities like iron ore or grain were fetching charter rates of $15,000 a day. Now, brokers and owners say, the going rate is $6,000 a day. If any customers can even be found.” [“Freighter Oversupply Weighs on Shipowners and Banks,” New York Times, 25 January 2012] Bradsher agreed that over-capacity is primary culprit. He wrote:

“Although the fault lies partly with doldrums in the global economy, the bigger factor is a glut of new freighters. The oversupply is putting financial pressure on the shipowners that bought them and the already struggling European banks that financed many of the purchases. Shipping industry leaders hold little hope of a quick recovery. ‘If the tunnel is 2012, I can’t see any light at the end of it,’ said Tim Huxley, the chief executive of Wah Kwong Maritime Transport Holdings, a Hong Kong-based shipping line with 29 bulk freighters and tankers. … For the shipping industry, the glut means not only lower charter fares, but also steep declines in the value of their vessels. The bigger losers, though, could eventually be some big European banks, many of which are already struggling with big losses on their holdings of government bonds from Greece, Italy and other heavily indebted European nations.”

Bradsher noted that “shipowners, meantime, are nervously monitoring an industry benchmark, the Baltic Dry Index of bulk freighter charter rates, which has lost more than half its value since the start of the year. The index is now at its lowest level since January 2009, during the depths of the economic downturn after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers.” He wrote that with “freight rates … close to operating costs for many bulk freighters” there was little profit available “to pay the mortgage” on new ships. As a result, he wrote, “More old vessels may be scrapped in the coming years, which would eventually reduce oversupply. … Meantime, bulk freighters, container ships, tankers and refrigerator ships by the hundreds may continue to bob idly in the waves, … their hulls showing wide bands of paint that would be submerged if the vessels were fully laden.”

The current crisis almost assures that ships will continue to steam more slowly to save costs. Other cost saving designs might also help. While it may sound foolish to write about new fuel-saving ship designs during a time when there are too many new ships being delivered, eventually such ships will probably be built — both to reduce operating costs and to reduce shipping’s carbon footprint. Several years ago, John Vidal reported, “Confidential data from maritime industry insiders based on engine size and the quality of fuel typically used by ships and cars shows that just 15 of the world’s biggest ships may now emit as much pollution as all the world’s 760m cars. Low-grade ship bunker fuel (or fuel oil) has up to 2,000 times the sulphur content of diesel fuel used in US and European automobiles.” [“Health risks of shipping pollution have been ‘underestimated’,” The Guardian, 9 April 2009] One of the new designs is for an automobile carrier that went into service in January. “The newly built Nichio Maru began its maiden voyage on January 7, 2012, and is the first coastal cargo ship in Japan to have photovoltaic solar panels installed.” [“Nissan unveils energy-efficient Nichio Maru car carrier,” by Darren Quick, Gizmag, 30 January 2012] Quick reported:

“There are 281 solar panels in all, fitted to the ship’s deck and used to power the LED lighting installed in the ship’s hold and crew quarters. Other energy efficiency features include the electronically controlled diesel engine that gives the 169.95 m (557 ft) long, 26 m (85 ft) wide vessel an operating speed of 21.2 knots (24.5 mph/39 km/h), and the use of a low friction hull coating that provides better sea mileage. Nissan says, when compared to an existing car carrier of the same type, these features allow the Nichio Maru to achieve a fuel reduction of up to nearly 1,400 tons annually, which translates to an annual reduction in CO2 emissions of 4,200 tons.”

Another proposed design, this one for dry bulk ships, has been developed by researchers at the University of Tokyo (UT) and a group of collaborators. Their design uses “a system of large, retractable sails measuring 64 feet (20 m) wide by 164 feet (50 m) high, which studies indicate can reduce annual fuel use on ships equipped with them by up to 30%.” [“Next-gen cargo ships could use 164-foot sails to lower fuel use by 30%,” by Randolph Jonsson, Gizmag, 24 April 2012] The following video provides an overview of the concept.

Although there may be no light at the end of the tunnel for dry bulk shippers this year, we know that dry bulk commodities are still going to transported around the world for a long, long time. We also know that the only economical way to transport those commodities is by sea. I agree with Tim Burt that shippers and carriers both have a stake in this future and that “there’s a case for collaboration here.”