Deaths related to the COVID-19 pandemic have now surpassed those associated with the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. It is estimated that around 675,000 people died in the U.S. during that latter pandemic and U.S. deaths associated with COVID-19 have now surpassed 700,000 and continue to climb. This staggering number of deaths deepens the meaning of this year’s traditional Mexican celebration of Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Despite its name, Día de los Muertos is a three-day celebration roughly corresponding to the European celebration of Halloween (31 October), All Saints Day (1 November), and All Souls Day (2 November). Unlike America’s Memorial Day, which is dedicated to remembering individuals who perished in wartime, Día de los Muertos is dedicated to remembering all departed relatives. Despite its ghoulish name, Día de los Muertos is not a somber, mournful time. Rather it’s a joyful celebration ensuring that the dearly departed remain an active part of a family’s heritage.

Día de los Muertos History and Traditions

Journalist Logan Ward notes, “Here’s one thing we know: Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is not a Mexican version of Halloween. Though related, the two annual events differ greatly in traditions and tone. Whereas Halloween is a dark night of terror and mischief, Day of the Dead festivities unfold over two days in an explosion of color and life-affirming joy. Sure, the theme is death, but the point is to demonstrate love and respect for deceased family members.”[1] Although there is a clear connection with the Catholic All Saints and All Souls Days, Ward explains, “Day of the Dead originated several thousand years ago with the Aztec, Toltec, and other Nahua people, who considered mourning the dead disrespectful. For these pre-Hispanic cultures, death was a natural phase in life’s long continuum. The dead were still members of the community, kept alive in memory and spirit — and during Día de los Muertos, they temporarily returned to Earth. Today’s Día de los Muertos celebration is a mash-up of pre-Hispanic religious rites and Christian feasts.” There are a number of traditions associated with this festival of joy.

Altars (Ofrenda). Shared family meals are as old as history itself. Sharing a meal with loved ones also lies at the heart of the Día de los Muertos celebration. According to the Dayofthedead.holiday (DOTDH) website, “The Aztecs used to offer water and food to the deceased to help them on their journey to the land of the dead. Now, Mexican families set up beautifully decorated altars in their homes and place photos of the loved ones they have lost along with other items. The ofrendas usually consist of water, the loved one’s favorite food and drink items, flowers, bread, and other things that celebrate the dead person’s life.”[2] As Ward notes, “These aren’t altars for worshipping; rather, they’re meant to welcome spirits back to the realm of the living.” The most commonly used flower, according to the DOTDH website, is the marigold (cempasuchil). The site notes, “Marigolds are used during Dia de Muertos celebrations by being placed on the altars and on the burial sites. The Marigold flower is thought to guide the spirits back with their intense color and pungent smell.”

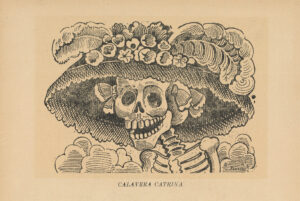

Skulls (Calaveras). For those of us not of Mexican heritage, Día de los Muertos is most recognizable by the painted skulls associated with the celebration. The DOTDH site notes, “Skulls are a huge part of the holiday. Skulls were used during rituals in the Aztec era and passed on as trophies during battles. Today, during Día de Los Muertos, small decorated sugar skulls are placed on the altars. There is nothing grim about these skulls. They are decorated with colorful edible paint, glitter, beads, and sport huge smiles.” According to Ward, “Sugar skulls are part of a sugar art tradition brought by 17th-century Italian missionaries. Pressed in molds and decorated with crystalline colors, they come in all sizes and levels of complexity.”

Literary Skulls (Calaveras Literarias). According to Wikipedia, “A distinctive literary form exists within this holiday where people write short poems in traditional rhyming verse, called (‘literary skulls’), which are mocking, light-hearted epitaphs mostly dedicated to friends, classmates, co-workers, or family members (living or dead) but also to public or historical figures, describing interesting habits and attitudes, as well as comedic or absurd anecdotes that use death-related imagery which includes but is not limited to cemeteries, skulls, or the grim reaper, all of this in situations where the dedicatee has an encounter with death itself. This custom originated in the 18th or 19th century after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future which included the words ‘and all of us were dead’, and then proceeding to read the tombstones. … In modern Mexico, calaveras literarias are a staple of the holiday in many institutions and organizations, for example, in public schools, students are encouraged or required to write them as part of the language class.”[3]

Costumes and Makeup. Costumes and face-painting were introduced into Día de los Muertos celebrations later than other traditions. Ward explains, “In the early 20th century, Mexican political cartoonist and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada created an etching to accompany a literary calavera. Posada dressed his personification of death in fancy French garb and called it Calavera Garbancera, intending it as social commentary on Mexican society’s emulation of European sophistication. ‘Todos somos calaveras,’ a quote commonly attributed to Posada, means ‘we are all skeletons.’ Underneath all our manmade trappings, we are all the same. In 1947, artist Diego Rivera featured Posada’s stylized skeleton in his masterpiece mural ‘Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park.’ Posada’s skeletal bust was dressed in a large feminine hat, and Rivera made his female and named her Catrina, slang for ‘the rich.’ Today, the calavera Catrina, or elegant skull, is the Day of the Dead’s most ubiquitous symbol.”

Concluding Thoughts

Your roots needn’t to be found in Mexico in order to remember your departed relatives. So many of our lives have been touched with sorrow this past year-and-half, I suggest we learn from Día de los Muertos celebrants and find joy in our memories. Break out those picture albums, 8mm movies, VHS tapes, and digital images and videos and be grateful for those who have touched our lives. Liam Callanan, an English professor and author, once wrote, “We’re all ghosts. We all carry, inside us, people who came before us.” That thought is in keeping with spirit (no pun intended) of Día de los Muertos and celebrating that spirit may help us cope better with the losses we continue to suffer as a result of the pandemic.

Footnotes

[1] Logan Ward, “Top 10 things to know about the Day of the Dead,” National Geographic, 26 October 2017.

[2] Staff, “History: Día de los Muertos,” Dayofthedead.holiday, 2019.

[3] “Day of the Dead,” Wikipedia.