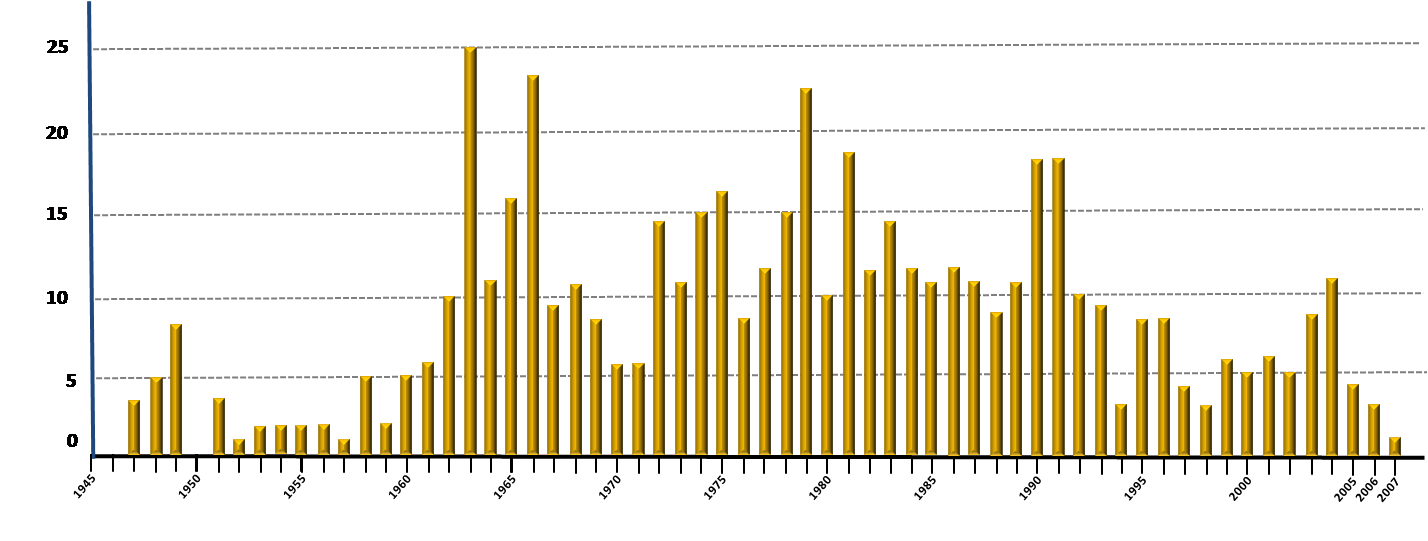

The eve of President-elect Barack Obama’s inauguration is a good time to reflect on the subject of peaceful transition of power. Although U.S. presidential elections are costly, interminably long, and often filled with lies and half-truths, there is a majesty associated with the post-election transition of power. President Bush, who was more often than not Obama’s target of choice during the elections, has been gracious to the next occupant of the White House during the transition period and has publicly wished him well. Not all transitions of power around the world are peaceful; although there are some encouraging signs. A short sidebar in a recent issue of The Economist trumpeted that “some stories are best told using graphs and charts.” In the magazine’s print edition, the story was titled “The death of the military coup“; they labeled it differently on their Web site. As shown in the attached image, the apparent demise of military coups is graphically impressive.

Of course the fact that recent years have witnessed fewer coups doesn’t mean that despots and would-be dictators aren’t still among us — Zimbabwe and Venezuela provide ample evidence of that. The graph does support the fact that democracy has made some halting strides over the past decade. Ghana provides a good African case study [“Ghana’s Example: How one African nation has made democracy work,” Washington Post editorial, 9 January 2009]. The editorial staff writes:

“African politics were shaped in the past year by two disastrous presidential elections — that of Kenya in December 2007, which ended in a fraud-marred impasse and triggered ethnic violence in which more than 1,000 people died; and Robert Mugabe’s first-round defeat and second-round theft of a Zimbabwean poll, which has prompted a catastrophic national collapse. But democracy in Africa is not dead, as the small but influential nation of Ghana demonstrated over the past month. Its two-round election for president ended with a razor-thin margin of victory for the opposition candidate. There was no major fraud or violence: The winning candidate, John Atta Mills, promised to ‘be president for all’; his opponent, Nana Akufo-Addo, accepted defeat and publicly congratulated his opponent. On being sworn in Wednesday, Mr. Atta Mills became the second opposition candidate to peacefully succeed an elected president since Ghana returned to democracy in 1992. A pioneer of Africa’s independence movement in the 1960s, Ghana is the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to accomplish that political feat. For the rest of the continent — including its giant and perpetually unstable neighbor, Nigeria — Ghana offers a demonstration that such political maturity pays off. Ghana’s average annual growth rate of 5.6 percent during the past six years has been one of Africa’s highest, and the country has become a favorite of foreign investors as well as donors.”

Ghanaians will have to celebrate a few more peaceful transitions before they can feel confident that democracy is likely to persist. Nevertheless, any peaceful transition of power in Africa is an event worth celebrating. As the editorial goes on to point out, democracy doesn’t mean that challenges disappear or that prosperity is assured.

“Mr. Atta Mills faces serious challenges, including growing transshipment of cocaine through Ghana to Europe — and the corruption that the drug trafficking has engendered. He will also need to skillfully manage the country’s recently discovered offshore oil, which could propel Ghana to greater prosperity or mire it in the political and economic diseases that afflict Nigeria and other petro-states. For now, however, the new president and his country can bask in the congratulations that have poured in from the European Union, the United Nations and the United States — not to mention from Ghana’s neighbors. ‘The conduct of the people of Ghana provides a rare example of democracy at work in Africa,’ said Kenya’s prime minister, Raila Odinga. As Mr. Odinga knows all too well, it’s an example from which Kenya, Zimbabwe and other states could learn.”

An earlier article in a different newspaper published just before the election, reminds us that democracy doesn’t automatically eliminate political abuses or corruption [“Ghana’s Image, Glowing Abroad, Is Beginning to Show a Few Blemishes at Home,” by Lydia Polgreen, New York Times, 22 December 2008]. Polgreen reports:

“Just a few years ago, democracy’s march across Africa seemed unstoppable. These days, it seems stalled: vote rigging in Nigeria, a convulsion of ethnic violence after disputed elections in Kenya and outright theft at the polls in Zimbabwe are among the most recent signs. That may be why those looking for reasons to be hopeful about democracy in Africa have their sights set on Ghana, the first sub-Saharan country to wrest independence from colonial power, and now a nation that appears to be bucking the antidemocratic trend.”

According to Polgreen, the people of Ghana are proud of their democracy, but, as the old adage says, “still waters run deep” and there are numerous issues bubbling just below the surface that could change the course of events there.

“Ghana has long been a favorite of foreign donors and Western governments in a region often known for brutal civil wars, corruption and tyranny. With its growing economy and squeaky-clean image, Ghana is a frequently cited success story. Yet roiling just below the surface are tensions over how the country has been governed, who is benefiting from economic growth and whether corruption is on the rise. Some people here worry that the country’s image as a bastion of peace and democracy is merely a sign of the low expectations outsiders have for Africa. ‘Let’s allow that Ghana has achieved some things,’ said Yao Graham, a writer and activist who leads the Third World Network, a research and advocacy institution with a regional office here. ‘But for this to be the yardstick of a continent is to set very low expectations for a billion people across Africa.'”

As noted earlier, the election was a hard-fought and close-run affair. In the end, it was likely the economy that tipped the balance toward the opposition. Sound familiar?

“The opposition said that the governing party’s record looked impressive on paper, but that in reality many Ghanaians found themselves worse off than before. ‘This has been a period of increasing corruption and a broadening gap between rich and poor,’ said James Gbeho, a senior opposition official who has served in many top government posts over the years. ‘For most people, progress has been an illusion.'”

Polgreen reminds us of Ghana’s recent history and how quickly democrats can turn in to despots.

“Ghana has long been a symbol of Africa’s vast promise, but also of the many pitfalls that have plagued the continent in the postcolonial era. After it won independence in 1957, the Pan-African ideas of Ghana’s founding leader, Kwame Nkrumah, helped inspire a generation of liberation struggles. But the dream soon soured. His ideas forged a strong national identity that helped Ghana escape the ethnic strife of many of its neighbors. Still, Mr. Nkrumah’s poorly planned efforts to quickly build an industrial economy drained the country’s treasury and hobbled its growth, historians say. Multiparty democracy gave way to single-party rule. The economy collapsed. Mr. Nkrumah, once seen as a hero for all of Africa, was overthrown by the military in 1966, and few here mourned his departure. He was exiled to Guinea, and in 1972 he died an angry, bitter man.”

Polgreen makes an interesting comparison between former British colonies to underscore the point that there is a big difference between “promise” and “performance.”

“Ghana’s slide was emblematic of the continent’s slumping fortunes, especially when compared to booming Asian nations. Ghana won its independence the same year as Malaysia, another former British colony. But 50 years later, Ghana remains among the poorest nations of the world, while Malaysia is far ahead of it in many measures of development, including per capita income, life expectancy, literacy and school enrollment. This African giant, it seemed, had feet of clay.”

Nevertheless, the word “promising” continues to crop up when people talk about Ghana. Ghanaians, however, are tired of hearing that their future “looks promising.” They want to see results.

“Like many countries on the continent, Ghana stumbled through seasons of shaky civilian government and iron-fisted military rule, only to emerge in 1992 as a multiparty democracy once again. Jerry Rawlings, the dashing and sometimes ruthless air force flight lieutenant who had first seized power in a coup in 1979, voluntarily gave up his military uniform and ran in elections. He won two four-year terms and stepped aside in 2000 when constitutional term limits barred him from running again. Ghana again became a bellwether of African progress, helping usher in an era of hope for peace and prosperity across the continent.”

Ghana is what my colleague Tom Barnett would call a Seam state. A country that lies between the disconnected and impoverished countries he calls the Gap and countries of the developed world he calls the Core. Seam states are moving in the right direction, but still suffer from many of the maladies that affect Gap states — including corruption and crime. Polgreen reports that Ghana finds itself in that very position.

“The country has become a hub of the growing cocaine trade between Latin America and Europe, and there have been indications from investigators that some government officials may have been involved. Corruption is widely perceived to be on the rise. Despite the economic growth, many people here say the wealth is not shared. … Indeed, the success of the opposition in the parliamentary elections was a surprising blow to the governing party. Across Accra, the capital, taxi drivers, shopkeepers and laborers exchange a finger-rolling gesture that is the universally acknowledged shorthand for the opposition’s slogan: change. But in Accra’s sleek new shopping mall, where the country’s small but growing middle class can buy flat-screen TVs, brand-name sneakers and plush imported furniture to a jangling soundtrack of Christmas carols, voters were more optimistic about the country’s current state. ‘Ghana’s future is very bright,’ said Larry Oppong-Attah, a 19-year-old student. As he tapped out text messages on a shiny Samsung cellphone, he said he hoped for a career in marketing.”

The biggest blow to Ghana’s future came with the downturn of the international economy and falling oil prices.

“Both parties … promised a raft of public spending, paid for by recent offshore oil discoveries. But the low price of oil may scuttle plans to drill. Gold is also essential to the country’s economy, and as with all commodities, its price has experienced some steep drops in recent months. ‘If you look at democracy as what a country offers its people, there are many questions to be asked,’ said Mr. Graham, the writer. ‘In Ghana we have growing inequality, an economy that is not creating jobs, and young people do not see a future here. By that standard, prospects for the future are not necessarily so bright.'”

The good news for Ghana is that oil prices are not predicted to remain low and its nascent oil sector may mature just as the global economy once again booms. The country is ripe for an approach like Development-in-a-Box™ because it has a relatively stable and secure environment, it needs to create jobs and diversify its economy, and it needs to control corruption and crime before they become the defining features of the country. Like the editors of the Washington Post, I applaud Ghana for pursuing democracy and the peaceful transition of power. At the same time, I encourage Ghana’s leaders to start quickly down the road that leads to better economic conditions through better governance and diversification.