In an interesting article on the Supply Chain Digest web site, editor-in-chief Dan Gilmore asks, “What are the most important supply chain innovations of all-time? Can they even be identified?” [“The Top 10 Supply Chain Innovations of All-Time,” 3 December 2010]. As President/CEO of a company that is getting ever more involved in the supply chain business, I found Gilmore’s list very informative. He begins:

“I have been working on this off and on for almost a year, and found it is difficult to pull together. The biggest challenge was that many innovations either have no clear origins, or maybe it was sort of a combined evolution along a number of fronts. This is especially true in terms of much technology innovation. For example, I have looked hard to see if there was some single company that invented the concept of supply chain network optimization software, but have so far stuck out. My sense is that it developed in parallel/collaboration among several academics. There is also not nearly as much source material in terms of supply chain history as I would have thought, as I will support with an anecdote in just a bit. I can’t say I had a crystal clear definition of what I was looking for, but it centered around this: Some innovation for which we can identify pretty clearly that some single company or individual(s) was/were responsible for the breakthrough [and] the innovation had a deep and lasting impact on supply chain practice.”

It is not surprising that many supply chain “innovations … have no clear origins.” That’s true of a lot of innovations. Often the greatest innovations occur when a number of existing technologies are combined in a new way. When that occurs, who should get credit for the innovation? The most obvious answer is the individual who was clever enough to have come up with the winning combination. Gilmore continues:

“So before the list, here is my anecdote. Several years ago, Jim Carr of PPG told me that he led the formation of a centralized transportation load control center at the company in the mid-1980s that he thought was the second or third one in the country, after 3M had pioneered the first one ever. I wanted to – and ultimately did – put 3M’s innovation on the top 10 list. But I had no detail. At first, I tried going through 3M’s communications group, thinking it might have something in its company history, or might at least point me to someone there who had been around at the time. Thought it might also be a nice thing to recognize for a company that prides itself on innovation. I can tell you that after several emails and several voice mails, I did not hear one thing back from anyone at 3M. I guess the communications group wasn’t communicating that month. So I tried my friend Paul Husby, who had been head of supply chain services at 3M in the early 2000s. Paul wasn’t around or involved at the time, but connected me with Gary Ridenhower, top supply chain exec earlier at 3M. While Ridenhower said he was ultimately in charge of the LCC development, he didn’t really know many of the details. He kindly said he would ask around. I was hopeful, but a few weeks went by, and nothing. I really thought the trail was cold and maybe dead. Then one day, an email from Gary shows up pointing me to Pete Andersen, who was in 3M’s logistics group at the time and now does some work for White Transfer. ‘He knows the details,’ Ridenhower said. And he does. My reason for relating this anecdote is that I really believe that if not for our efforts, this story would simply have been lost forever. I think it is worth cataloging as SCM history. Thanks to both Gary and Pete for their efforts.”

Historians take heart. Leo Tolstoy once pejoratively wrote, “Historians are like deaf people who go on answering questions that no one has asked them.” Gilmore is not only asking questions about the past, he’s listening for the answers. In presenting his Top 10 list, Gilmore promises to follow up with a “more detailed article/pdf” and “a video version.” Gilmore acknowledges that “Top” lists are subjective and subject to criticism and disagreement; but, he writes, “Hey, that’s the fun of this from our view.” With that, he begins:

“No. 10: Taylorism: In the late 1800s, the great Frederick Taylor takes the first scientific approach to manufacturing. In the early 1880s, he invents the concepts of using time studies on the factory floor, and based on that work, the notion of ‘standard times’ for getting specific tasks done. [He] later develops the concept of incentive systems and piece-rate pay plans. Taylor’s ideas were simply seminal – and often controversial – and dramatically influenced the practice of manufacturing over the next few decades and even to this very day.”

I’m not sure all workers appreciated Taylor’s work. Gilmore is correct, however, that his ideas changed the manufacturing landscape forever. Taylor’s four principles of scientific management were:

“1. Replace rule-of-thumb work methods with methods based on a scientific study of the tasks.

“2. Scientifically select, train, and develop each worker rather than passively leaving them to train themselves.

“3. Cooperate with the workers to ensure that the scientifically developed methods are being followed.

“4. Divide work nearly equally between managers and workers, so that the managers apply scientific management principles to planning the work and the workers actually perform the tasks.” [“Frederick Taylor and Scientific Management,” NetMBA.com]

Taylor’s work opened a new career path for efficiency experts. I’m reminded about the story of an efficiency expert who concluded his lecture at one company with a note of caution. “You don’t want to try these techniques at home.” “Why not?” asked somebody from the audience. “I watched my wife’s routine at breakfast for years,” the expert explained. “She made lots of trips between the refrigerator, stove, table and cabinets, often carrying a single item at a time. One day I told her, ‘Hon, why don’t you try carrying several things at once?'” “Did it save time?” the person in the audience asked. “Actually, yes,” replied the expert. “It used to take her 20 minutes to make breakfast. Now I do it in seven.” Gilmore continues:

“No. 9: 3M’s Transportation Load Control Center: In 1982, 3M, like every other company, had to leave transportation decisions to each plant and distribution center. Roy Mayeske, at that time the Executive Director of 3M Transportation, had the idea to centralize transportation planning to look for network synergies. 3M took mainframe software being used by Schneider National – one of its major carriers – and modified it to be workable from a shipper perspective. Ship sites called in planned shipments; carriers and routings were phoned back. The LCC is now of course a standard practice today.”

I suspect that Gilmore will fill in more of the details about this story when he publishes his lengthier article on this topic. He continues with number eight on his Top 10 list:

“No. 8: Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP): In the late 1970s, Andre Martin ran operations for Abbott Labs Canada, and found himself caught between manufacturing and distribution managers, who could never seem to get inventory questions right and always blamed each other. Realizing that what was needed was a sort of Manufacturing Resources Planning for inventory distribution, Martin led a successful effort to build the first computerized DRP system, which in turn led to a book that created the software category of DRP, as several technology firms built products based on these ideas. [This innovation] was in many way[s] the start of today’s supply chain planning software industry.”

Since supply chain planning software is now a large part of Enterra Solutions’ business portfolio, I give a tip of the hat to Mr. Martin and Abbott Labs Canada. It seems to me that the implementation of DRP could also be tapped as the moment that industrial age business silos started to crumble in favor of a more collaborative business environment. The silos haven’t broken down completely, but most businesses are much better now than they were 40 years ago. On to number seven:

“No. 7: The FedEx Tracking System: After re-inventing the category of express parcel shipments, FedEx went a step further in the mid-1980s with its development of a new computerized tracking system that provided near real-time information about package delivery. Outfitting drivers with small handheld computers for scanning pick-ups and deliveries, a shipment’s status was available end to end. The Fedex system really drove the idea that ‘information was as important as the package itself,’ and was foundation of our current supply chain visibility systems and concepts.”

Clearly package tracking is deserving of kudos in anybody’s Top 10 list. It helped businesses take another step away from the industrial age and into the information age.

“No. 6 – The Universal Product Code: Though the idea to use some form of printed and even wireless automatic product identification had been around for decades, lack of standards had precluded individual ideas from gaining any sort of critical mass. In 1970, a company called Logicon wrote a standard for something close to what became known as the Universal Product Code (UPC) to identify via a bar code a specific SKU, an effort that was finalized a few years later by George Laurer. The first implementation of the UPC was in 1974 at a Marsh’s supermarket in Troy, OH north of Dayton. The invention triggered the auto ID movement, forever changing supply chain practice and information flow.”

I’m pleased that “standards” were highlighted somewhere on Gilmore’s list. As I have noted in a previous post discussing RFID tags, one of the challenges that has kept them from becoming more ubiquitous is the lack of common standards. Just like road and rail traffic flow better because standards are available and enforced, information and goods also flow better when standards are available and enforced.

“No. 5: The Ford Assembly Line: Henry Ford actually got the idea for the assembly line approach from the flow systems of meat packing operations in the Midwest, but it was Ford’s adoption of the production approach with a continuously moving line for Model T’s in 1913 that revolutionized not only automobile assembly but took the practice of manufacturing to new levels in other sectors as well. Total time of assembly for a single car using the production line fell from 12.5 labor hours to 93 labor minutes, ultimately making cars affordable for the masses, changing not only supply chain but society.”

Undoubtedly, the assembly line changed society. Its implementation, however, was problematic for affected workers. Assembly lines are probably better suited for robots than people, who can get bored easily and are subject to repetitive stress injuries. Nevertheless, I agree with Gilmore that the assembly line deserves a spot in the Top 10. He continues:

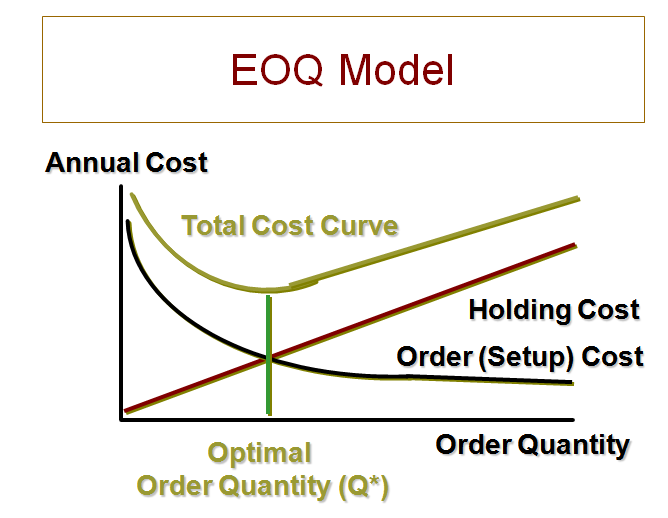

“No. 4: Economic Order Quantity (EOQ): Economic Order Quantity is a mathematical approach for determining the financially optimal amount of product to order from suppliers based on inventory holding costs and ordering costs. The original concept is generally credited to Ford Whitman Harris, a Westinghouse engineer, from an article in 1913, but it was a much later article in the Harvard Business Review in 1934 by RH Wilson that made EOQ mainstream. The formulas are still taught today, and the basis for much supply chain decision-making even in this era.”

While management practices come and go, mathematics are timeless. You can read more about Economic Order Quantity on Wikipedia. A simple graph helps explains the logic behind EOQ.

As Michael Hugos writes, “The EOQ formula works to calculate an order quantity that results in the most efficient investment of money in inventory. Efficiency here is defined as the lowest total unit cost for each inventory item.” [“Essentials of Supply Chain Management,” second edition, p. 61] Gilmore continues:

“No. 3: The Ocean Shipping Container: It is hard to imagine today, but until the mid-1950s, there was no standard way to ship products on ocean carriers, and most were shipped on whatever container or platform the producing company deemed best. The result was terribly inefficient handling on both sides of the equation, poor space utilization on the cargo ships, and high logistics costs. Enter Malcom McLean, legendary logistics entrepreneur and visionary who invented the standard steel shipping container first implemented in 1956 at the port of New Jersey. Someone would have thought of it eventually, but McLean’s invention started the explosion in global trade.”

To give you some idea about the importance of maritime trade, it is estimated that, by volume, ninety percent of world trade is moved by ocean transportation. Not all of that volume is moved in containers. Other forms of maritime transportation include: liquid-bulk (petroleum products), dry-bulk (coal and grains), break-bulk (dry non-bulk cargo on pallets), and neo-bulk (loose cargo of common size as automobiles). I can certainly agree with Gilmore, however, that when it comes to supply chain innovations the development of standard container sizes deserves to be near the top of the list. He continues:

“No. 2: P&G’s Continuous Replenishment: Until 1987 or so, order patterns in the consumer goods supply chain were almost totally dependent on whatever the manufacturer sale person and retail buyer decided between them. That’s until Procter & Gamble bought a mainframe application from IBM for ‘continuous replenishment’ (which had been deployed a handful of times in other markets), re-wrote it for consumer goods to retail, and as a result dramatically changed that entire value chain by driving orders based on DC withdrawals and sales data. P&G first implemented the approach with Schnuck’s Markets in St. Louis, with dramatic results in both lowering inventories while increasing in-stock at retail. KMart was next, taking pipeline diaper inventories from two months to two weeks – but KMart never completely embraced the possibilities. A legendary 1988 meeting between P&G’s CEO and Sam Walton led to a CR program there and changed supply chain history, helping propel Wal-Mart to retail dominance and providing the foundation for Efficient Consumer Response (ECR), Category Management, Continuous Planning, Forecasting and Replenishment (CPFR), and more.”

It’s difficult to imagine that continuous replenishment didn’t top the list. After all, when retailers are out of stock they are essentially out of business. Continuous replenishment is the foundation upon which the vision of demand-driven supply chains is built. So what topped Gilmore’s list?

“And finally…. (drum roll…envelope please)… No. 1: The Toyota Production System: When James Womack and several co-authors wrote ‘The Machine that Changed the World’ in 1990, it was of course not a Toyota car that had such an impact, but rather the Toyota Production System (TPS) that was the foundation of the company’s dramatic success across the globe. Pioneered by Toyota’s Taiichi Ohno and a few colleagues, TPS not only is the foundation for today’s Lean manufacturing and supply chain practices, but the concepts have penetrated … every area [of] business. TPS truly did change the world.”

David Blanchard writes, “The TPS is based on the concept of continuous improvement, which is reinforced by a corporate culture that empowers employees to improve their work environment.” [“Supply Chain Management: Best Practices,” p. 94.] Blanchard notes, however, that TPS “was based on concepts popularized even earlier in the twentieth century.” He specifically mentions the ideas of Henry Ford. Most innovators agree with Sir Isaac Newton who said, “If I have seen further it is only by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Gilmore has done a great job of identifying some of the giants that have helped move supply chain innovation forward.