Stephen Colbert on his Comedy Central show “The Colbert Report,” said, “Warren Buffett is so rich he just hired Bill Gates to spend his money. It’s a great day for capitalism!” That’s a funny line, but it also reflects reality. During a press conference following the announcement of Buffet’s gift, Bill Gates said, “It’s scary. If I make a mistake with my own money, it isn’t as big as making a mistake with Warren’s money.” To which Mr. Buffett replied: “I won’t grade you more often than daily.” [“Buffett’s Billions Will Aid Fight Against Disease,” by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., and Rick Lyman, New York Times, 27 June 2006] The combined totals of Gates’ and Buffet’s philanthropy is truly staggering, but, even with that much money, doing the right thing (i.e., spending it to achieve the greatest impact) is still difficult.

“‘It’s incredibly difficult to give this much money away well,’ said Jean Strouse, a biographer who has compiled an oral history project on the Gates Foundation. ‘And giving it away to people who can use it well, especially in places where poverty is so overwhelming, where there’s not much real infrastructure.'”

Strouse hit the nail on the head. You can’t parse development into its separate parts and expect to achieve societal transformation. It was recognition of that point that caused Tom Barnett and me to come up with the concept of Development-in-a-Box™. Our concept takes an holistic approach to development. Medical advances, the area in which Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has concentrated much of its time and effort, will never reach those who need them without a sustainable infrastructure to make that happen. The Gates and Buffet would be wise to invest in medical schools and healthcare training as well as in research & development of critically needed medicines. The World Health Organization estimates there is a shortage of 4 million healthcare workers in developing nations. [“Doctor shortage critical in developing world: WHO,” by Shapi Shacinda, The Namibian, 06 April 2006] By tying scholarships to commitments to remain in the developed world, their efforts would achieve the greatest effects. Currently about 25 percent of doctors and nurses from Gap countries practice in Core nations.

“Zambian Vice President Lupando Mwape, speaking at an event marking World Health Day in Lusaka on Friday, said the shortage of doctors and nurses was sending many Africans to their graves. ‘The shortage of medical personnel has now reached its peak and this is resulting in many deaths which could otherwise be avoided,’ Mwape said. ‘About 600 000 people in Sub-Saharan Africa die from tuberculosis annually while 800 000 children die from communicable diseases,’ he said. British-based charity Oxfam says there is one doctor per 14 000 people in Zambia compared with the ratio of 1 to 600 in Britain.”

Shacinda’s article underscores why an holistic approach is necessary. He notes that NGOs blame the IMF for the healthcare crisis, because the IMF restricts how much nations can spend on healthcare and still qualify for assistance. One of the things that Bono is trying to achieve with his celebrity is bringing nation-states, international organizations, and NGOs together in some systematic way to address poverty and disease in the developing world. Unfortunately, he lacks a framework, which is a gap that Tom and I believe Development-in-a-Box fills.

One of the arguments we hear against this approach that is that there is no one in charge to make this happen. The UN has become nearly impotent (and Congress would never let it be in charge), the rest of the world has become skeptical of U.S. intentions, and no other nation or group has the capacity or will to lead such an effort (even if they could get a mandate to do so). That leaves what is known in security circles as “coalitions of the willing.” I prefer the term “communities of practice.” There is Web site devoted to the topic [Communities of Practice and Community-enabled Strategic Results from Self-Organisation] and I really like its full title. Community-enabled Strategic Results from Self-Organization is exactly what Development-in-a-Box is trying to achieve. The reason that we stress that Development-in-a-Box is a standards-based approach is because we know that “results” must be measured in order to determine progress and to permit one to make necessary course corrections. One of the chief proponents of this approach, Etienne Wegner, wrote some 8 years ago [Communities of Practice: Learning as a Social System]:

“We now recognize knowledge as a key source of competitive advantage in the business world, but we still have little understanding of how to create and leverage it in practice. Traditional knowledge management approaches attempt to capture existing knowledge within formal systems, such as databases. Yet systematically addressing the kind of dynamic ‘knowing’ that makes a difference in practice requires the participation of people who are fully engaged in the process of creating, refining, communicating, and using knowledge. We frequently say that people are an organization’s most important resource. Yet we seldom understand this truism in terms of the communities through which individuals develop and share the capacity to create and use knowledge. Even when people work for large organizations, they learn through their participation in more specific communities made up of people with whom they interact on a regular basis. These ‘communities of practice’ are mostly informal and distinct from organizational units.”

The aims of Development-in-a-Box are not just setting up infrastructure, automating processes, and establishing standards, they also include investing heavily in indigenous human capital. That means that local populations become an intimate part of the community of practice associated with Development-in-a-Box. Wegner defines a community of practice this way:

“Members of a community are informally bound by what they do together–from engaging in lunchtime discussions to solving difficult problems–and by what they have learned through their mutual engagement in these activities. A community of practice is thus different from a community of interest or a geographical community, neither of which implies a shared practice. A community of practice defines itself along three dimensions:

- What it is about – its a joint enterprise as understood and continually renegotiated by its members

- How it functions – mutual engagement that bind members together into a social entity

- What capability it has produced – the shared repertoire of communal resources (routines, sensibilities, artifacts, vocabulary, styles, etc.) that members have developed over time.

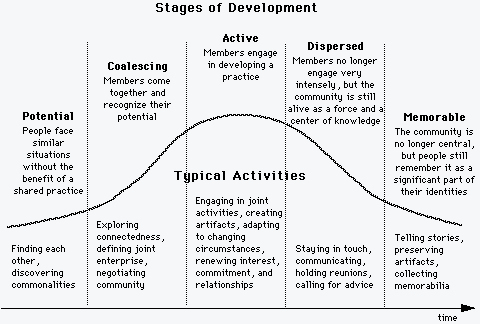

“Communities of practice also move through various stages of development characterized by different levels of interaction among the members and different kinds of activities.“

I would add “standards” to the capabilities portion of that definition. One of the reasons that communities of practice and Development-in-a-Box are so complementary is that a standards-based approach permits the kind of plug-and-play voluntary participation that such communities require. The reason that any successful approach will have to be plug-and-play is that progress in different sectors will vary. Some goals will be achieved before others. Wegner believes that communities of practice go through various stages that demonstrate how they get together and why they dissolve. Those stages are depicted in the following figure:

Another important characteristic of communities of practice is that they can work using a variety of different relationships. The Gates Foundation doesn’t have to maintain a formal relationship with Doctors Without Borders, for example, in order for them to be working on achieving the same goal. They can, however, recognize the same reporting standards so that they can talk with one another about progress their various programs are making. Wegner defines communities of practice relationships this way when they are found within an organization:

Relationship Definition Challenges typical of the relationship

| Bootlegged | Only visible informally to a circle of people in the know | Getting resources, having an impact, keeping hidden |

| Legitimized | Officially sanctioned as a valuable entity | Scrutiny, over-management, new demands |

| Strategic | Widely recognized as central to the organization’s success | Short-term pressures, blindness of success, smugness, elitism, exclusion |

| Transformative | Capable of redefining its environment and the direction of the organization | Relating to the rest of the organization, acceptance, managing boundaries |

One can imagine that such relationships would be similarly defined when communities of practice exist between organizations. The kind of relationships we are most interested in forming as part of the Development-in-a-Box approach are the strategic and transformative relationships. I believe that groups who sincerely believe the world can become a better place will be able to achieve “Strategic Results from Self-Organization.” It’s certainly something worth talking more about.