“Everyday supply-chain transactions pose some of the biggest fraud, waste, and abuse risks companies face,” asserts Sabine Vollmer. “But few companies are equipped to monitor the risks or detect breaches with the help of analytics, according to a global survey conducted by Deloitte.”[1] Trying to make a profit in a tight economy is difficult enough without the added costs that result from nefarious activity. Supply chain complexity is one of the contributing factors that criminals count on to cover their criminal activity; and it appears to be a contributing factor regardless of the type of supply chain involved. For example, Christopher Elliott (@QUBFoodProf), a professor from Queen’s University in Belfast, found that complexity contributes to fraud in the food supply chain. In fact, he believes the food supply chain is “ripe for fraudulent activity.”[2] “I believe criminal networks have begun to see the potential for huge profits and low risks in this area,” he said. “A food supply system which is much more difficult for criminals to operate in is urgently required.” Interest in Elliott’s study was heightened when the horse meat scandal rocked the United Kingdom in 2013. The area most vulnerable to fraudulent activity, according to Elliott, is procurement. Again referring to the meat industry, he stated, “Traders and brokers will buy and sell meat of any quality or quantity. Most traders don’t have physical possession of the meat that they buy and sell. They trade from an office, even over a mobile phone, while the meat will more than likely be held in a cold-store. They may never own the meat, but merely arrange the deal.” Obviously, the food industry isn’t the only sector vulnerable to such fraudulent transactions.

Supply chain complexity breeds ignorance. Vollmer reports that the Deloitte survey found that “of the 3,600 executives and managers polled, 47% did not know whether their company had experienced fraud, waste, or abuse in its supply chain during the past 12 months. Meanwhile, 50% said they did not know how often their company monitored its third-party suppliers, shippers, and vendors.” Mark Pearson, a principal with Deloitte Financial Advisory Services and a fraud investigator, told Vollmer that he was surprised at the high number of respondents who didn’t know about supply-chain fraud, waste, and abuse incidents. Ignorance is never a good thing, especially in business. Financial services enterprises have for years successfully used big data analytics to detect and prevent fraudulent activity. More industries could learn from their successes. Unfortunately, the Deloitte survey determined that less than 10% of the companies polled were using analytics to mitigate fraud, waste, and abuse risks in the supply chain. “Another 18% of the companies were in the process of building such analytics programs. Thirteen per cent lacked the ability to fully use them, and 22% used no analytics at all to manage financial risks in the supply chain. The remaining 40% said they did not know whether their companies used such programs.”

I have argued in previous articles that one way to reduce supply chain complexity is by letting cognitive computing systems handle many of the routine business decisions and transactions companies must make. Cognitive computing cannot only automate decisions and processes (thus freeing decision-makers to concentrate their efforts where they can be more effective) they can often be adopted to engage in fraud prevention at the same time. Deloitte’s Pearson suggests that companies ask seven questions to help reduce the corporate risk of fraud, waste, and abuse in the supply chain. Those questions are:

- Have all related parties been identified and factored into the risk-ranking of items to test?

- How co-operative and responsive is the vendor?

- Does the support provided validate the transaction?

- Does the support provided in its entirety provide the ability to evaluate the ‘weight of the evidence’ underlying the transaction?

- Is there sufficient detail describing the item to justify its being invoiced?

- Are there any notations (handwritten or otherwise) that may provide useful information about the transaction?

- If the items invoiced do not have an associated pre-approved rate, is there precedent for the rate change?

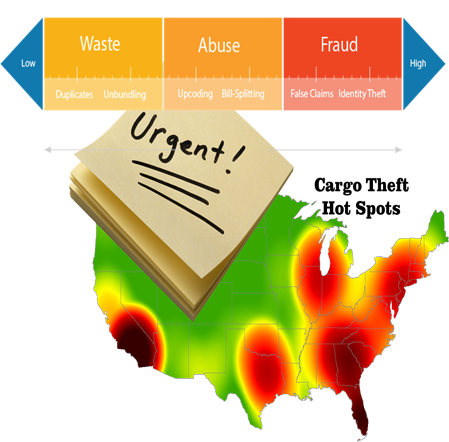

Rules that monitor transactions to determine answers to some of those questions can be built in to cognitive computing solutions. Cognitive computing systems can also be employed to help prevent cargo theft when they are connected to monitored shipments. Hailey Lynne McKeefry (@HaileyMcK) asserts, “Every year, in the United States alone, cargo theft is rampant and increasingly more sophisticated. To cope, … supply chains have to increase visibility to combat loss. … Every day, companies are robbed of a half million dollars of stolen goods, with 90% of thefts associated with unattended trucks, according to the report.”[3] McKeefry believes that mobile technologies and cloud computing, two important components of the Internet of Things, can be used to help reduce cargo theft, especially when that data can be analyzed for insights. She explains:

“Sensors, which are becoming increasingly affordable, allow organizations to monitor containers, palettes, or even individual products, depending on the need. The delivery of software services in the cloud allows for a variety of benefits, including ease of use and scalability. These elements will bring track and trace of products into the affordable mainstream. … Investing in technology allows organizations greater visibility and greater granularity of information about shipments. In addition, it’s possible to monitor on a frequent basis. … In the case of theft, this type of monitoring may not prevent theft, but over time collected information can be used in predictive ways to reduce risk.”

A recent Deloitte survey found that, in companies that had experienced fraud, employees were a significant source of the problem (22.9% of the time).[4] Deloitte’s Pearson stated, “Don’t fall into the ‘it can’t happen at my company’ trap. Forces outside your company aren’t always to blame. Employees often leverage transactions involving vendors and third parties to their own benefit via supply chain fraud — and when collusion is involved, detection and prevention is quite difficult.” Even good technology can’t compensate completely for bad people — but it can help. Since cognitive computing systems learn as they work, they can detect unusual and abnormal activity. That should be especially helpful since most fraud (nearly 77% of it) was not the result of bad employees. “Vendors were the culprit 17.4% of the time and other third parties, which would include subcontractors and their vendor, accounted for 20.1% of the fraud.”

The challenges associated with fraud, waste, theft, and abuse are not new and they are not going away. Back in 2008, Thomas Wailgum (@twailgum) wrote, “Enterprises have discovered that their businesses are ripe for fraud and theft as they rely more and more on global outsourcing relationships, complex networks of suppliers and vast computer networks to conduct business.”[5] He went on to note that this “ripeness” was due to supply chain complexity. “Supply chain success and, conversely, the prevalence of fraud, have to do with control, or, in this case, 21st century enterprises’ lack of control due to the expansive and complicated nature of global supplier networks.” Supply chains are not getting less complicated so companies would be wise to employ emerging technologies to help fight fraud, waste, theft, and abuse.

Footnotes

[1] Sabine Vollmer, “Identifying fraud, waste, and abuse in the supply chain,” CGMA Magazine, 14 October 2014.

[2] “Complex supply chains leave industry open to fraud,” World Fishing & Aquaculture, 13 January 2014.

[3] Hailey Lynne McKeefry, “Intelligent Supply Chain Fights Theft, Loss,” EBN, 22 April 2015.

[4] “Who is Causing Supply Chain Fraud?” Material Handling & Logistics, 22 May 2015.

[5] Thomas Wailgum, “Fraud and Theft Risks in Global Supply Chains Are Everywhere,” CIO, 30 April 2008.