For years I’ve heard people argue that jobs are leaving the U.S. because companies are simply looking for cheap labor to exploit. While I can’t argue against the truth that many companies relocate plants to countries where labor costs are cheaper, cheap labor is only one factor that manufacturers consider. If cheap labor were the most important factor, Haiti would be flush with companies scrambling to relocate there. We all know, however, that companies aren’t relocating to Haiti and the unemployment rate there is disastrous. The reason that companies avoid Haiti is that its business environment is toxic. Despite conditions found there, the government of Haiti is desperately trying to attract foreign investors (“Still Fragile, Haiti Makes Sales Pitch,” by Marc Lacey, New York Times, 5 October 2009]. Lacey was reporting from Haiti’s capital, Port Au Prince, on an “investment conference” held there — apparently with little success.

“It did not appear that a single new deal was signed … at a two-day investment conference in Haiti, the poorest nation in the hemisphere. But the simple fact that hundreds of potential investors showed up to network and discuss possible projects created hope in a country that has been long shunned as too unsafe to visit, never mind invest in.”

Haiti’s lack of success in attracting investors is not really surprising. In my discussions about Development-in-a-Box™, I have stressed that countries are not going to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) successfully until they have established some necessary preconditions. Among those conditions are security (which Haiti lacks), an educated and healthy work force (adult literacy is only 56%), a minimum level of infrastructure (also needed in Haiti), and a decent business environment (Haiti is filled with corruption). Lacey points out that Haiti is used to seeing foreigners in town, not just foreigners dressed in business suits.

“Haiti is used to well-meaning foreigners, most of them relief workers, peacekeepers and missionaries. But this was a new group: profit-minded people assessing Haiti based on its bottom line — and in the midst of an economic crisis, no less.”

The question remains: Does Haiti have any real hope of attracting businesses to its shores? The answer is “maybe.” Lacey continues:

“In one conference room, a group of businessmen in dark suits was discussing how brassieres could be made at low cost and high profit here. One room over, mangos were the topic at hand. Investors insisted that money-making opportunities were everywhere in Haiti. ‘The investment climate is much warmer than the temperature in this room,’ said Gilles Rivard, the Canadian ambassador to Haiti. There were big names, too. Gap, Levi Strauss and American Eagle Outfitters were here, all interested in the potential of American trade legislation that wipes out duties on apparel assembled in Haiti. Citibank and Scotiabank were on hand to discuss loans. Former President Bill Clinton, the United Nations special envoy to Haiti, gave his stamp of approval as he visited last week, declaring the country as safe as it has been in years and pledging to help investors navigate Haiti’s notorious red tape.”

Still, as noted above, no apparent deals were struck. Despite “money-making opportunities everywhere in Haiti,” conditions remain abysmal. In the World Bank’s latest Doing Business Index, Haiti ranks 151st out of 183 rated nations. When it comes to “starting a business” in Haiti, it ranks 180th out of 183 ranked countries. In Transparency International’s 2008 Corruption Perception Index, Haiti ranks 177th out of 180 ranked countries. I guess the only good news is that the current ranking is actually an improvement. In the 2006 index, Haiti ranked dead last. The only countries ranked lower than Haiti today are Iraq, Myanmar, and Somalia. All of this makes one wonder why Haitian leaders believe they can attract FDI. Lacey’s report continues:

“That Haiti needs the attention cannot be overstated. Unemployment hovers at around 70 percent, experts say, and over half of the population lives in extreme poverty. Violence broke out in June as students demanded an increase in the minimum wage to $5 from $1.75 — which were daily rates, not hourly ones. Haiti’s extremely low labor costs, comparable to those in Bangladesh, make it so appealing. Still, investing in Haiti, those who operate in the country say, is not for the faint of heart. Water and power are off as much as they are on. The government, despite its overtures to investors, can tie up deliveries at the ports. Bribes are common. So are street protests. With 19 political parties jockeying for power, a deep rich-poor divide and legislative and presidential elections looming in the next two years, United Nations soldiers are an essential element in keeping the country from becoming unhinged. Haiti, so used to suffering, is caught in a paradox. Jobs are an essential element to quelling the country’s social tensions. But companies require stability before they will create any jobs.”

With unemployment running so high, the best of Haiti’s citizens are eager to leave for greener pastures. A lack of opportunity translates into a lack of hope. Anger and frustration continue to make Haiti’s streets unsafe and foreign business people wary. You can sense the desperation in the pleas for investment from Haiti’s leaders.

“‘Don’t be afraid,’ Maxime D. Charles, the head of Haiti’s banking association, told investors. ‘Not everything is roses,’ warned Fabricio Opertti, a loan program coordinator at the Inter-Amercian Bank who helped organize the event. ‘Major security issues have been addressed, but there does seem to be a fragile state,’ said Mark D’sa, a production manager for Gap. The State Department in July downgraded its travel warning for Haiti, which no longer advises Americans to avoid nonessential travel to the country. Whether that means Haiti is safe remains a matter of interpretation. … Part of the task at hand, organizers of the conference said, is improving Haiti’s reputation. ‘You don’t change reputations overnight in countries or human beings,’ said Luis Alberto Moreno, the president of the Inter-American Development Bank, who said he, as a Colombian, knew how long it took to change perceptions of a troubled place. The Haitian economy has been reeling from a number of setbacks over many years. Just last year, a string of hurricanes cost the country $1 billion in damages, or 15 percent of its gross domestic product.”

As elsewhere in the world, but especially in the developing world, there is a desperate need for jobs in Haiti. Jobs equal opportunities and opportunities equal hope. Lacey concludes his report by noting that hope remains in short supply in Haiti.

As for the conference, Haitian officials hoped all the talk would result in signatures, joint ventures, profits and jobs. ‘We don’t want this to be just talk,’ said Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis, Haiti’s prime minister. ‘We want concrete proposals. By the end of the year, we want to feel the effects of this meeting.’ To the restless population, who struggle to get by and doubt their leaders care much, she said simply, ‘Patience.'”

The U.S. State Department’s country notes on Haiti state:

“Haiti now ranks 146th of 177 countries in the UN’s Human Development Index. Haiti’s economic stagnation is the result of earlier inappropriate economic policies, political instability, a shortage of good arable land, environmental deterioration, continued reliance on traditional technologies, under-capitalization and lack of public investment in human resources, migration of large portions of the skilled population, a weak national savings rate, and the lack of a functioning judicial system. … Private domestic and foreign investment has returned to Haiti slowly.”

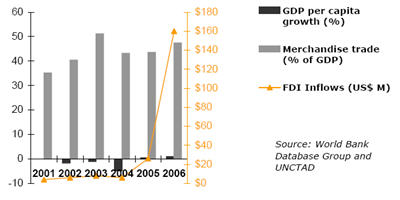

FDI has returned slowly indeed. The recession was particularly devastating on Haiti because FDI had just started flowing again into the country as the attached figure shows.

In it’s 2008 World Investment Report, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) ranked Haiti 105th out of 141 countries on “Inward FDI performance” and 139 out of 141 on “Inward FDI Potential” — and that was before the recession hit. To overcome both realities and perceptions of challenges in Haiti, the country is bent on establishing special economic zones to attract FDI [“World Bank Group to Help Improve Haiti’s Industrial Zones, Encourage Private Investment,” Media-Newswire.com, 30 September 2009].

“The International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Investment Climate Advisory Services of the World Bank Group launched a project with Haiti’s government and private sector to improve the framework for special economic zones and to attract new investment. The project will be funded with $1.26 million from the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the government of the Wallonia Region of Belgium with implementation taking place over the next two years. It is expected to generate $30 million in investments and 9,500 new jobs in the four years following implementation. To fully leverage its potential and the trade benefits of the U.S. HOPE II legislation, which extends tariff preferences on certain manufactured products, Haiti needs to attract foreign investors and expand industrial space. The new project will help develop additional industrial space and expand factory capacity by sharing best practices on multi-shifts. It also will revamp the regulation of Haiti’s industrial parks and free zones into a comprehensive special economic zones framework, and help develop the necessary tools to attract foreign investors and retain existing ones.”

The anticipated 9,500 jobs is a start, but Haiti needs over 2 million jobs for its unemployed work force. Haiti has been a conundrum for U.S. foreign policy for decades. Not only is it a desperately poor neighbor, economic refugees from Haiti have tried reaching U.S. shores for decades. Haiti will remain a conundrum until its cycle of poverty can be broken and it can find path toward prosperity. Taking the first steps along that path remains up to the Haitians themselves. As the recent investment conference demonstrates, they are at least facing the right direction even if they haven’t started moving down the path.