As last year was ending and the new one beginning, the folks at SupplyChainBrain featured a number of articles about lean business practices. Since several supply chain analysts continue to point out that there is a natural tension between proponents of lean supply chains and proponents of resilient supply chains, I thought a post on the subject of “lean practices” was in order. In a previous post, I wrote:

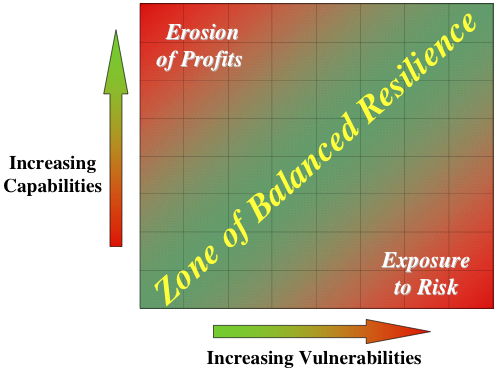

“Time and again the issue of balance between “lean” and “resilient” supply chains is raised by risk management experts. In his doctoral dissertation entitled Supply Chain Resilience: Development of a Conceptual Framework, an Assessment Tool and an Implementation Process, Timothy J. Pettit, included a graphic that, in a very general way, illustrates why balance is the key.

“Pettit’s point is that resiliency does come with a price that can erode profits. A lack of resiliency, however, can also affect profits and even expose a company to total failure. Hence, finding what Pettit calls the ‘Zone of Balanced Resilience’ is essential. In his abstract, Pettit writes, ‘The business environment is always changing and change creates risk. Managing the risk of the uncertain future is a challenge that requires resilience – the ability to survive, adapt and grow in the face of turbulent change. … Findings suggest that supply chain resilience can be assessed in terms of two dimensions: vulnerabilities and capabilities.'”

Lean practices are aimed at maximizing profits while resilient practices are aimed at mitigating potential supply chain disruptions. With that background in mind, let’s look at the first short article published by SupplyChainBrain [“Does Lean Make a Good Company Great?” 29 December 2011] The editorial staff writes:

“Simply stated, Lean alone won’t make a company successful, but even a successful company could improve immensely if it adopted a number of Lean practices, says Kenneth McGuire, a management consultant with Management Excellence Action Coalition. For the last 30 years, MEAC has helped companies in manufacturing improve so they can boost productivity. Lean is one of the ways to do that because it is among the competitive norms against which companies will be measured. After all, there’s an immediacy in delivery that’s required by most customers now, a perfection in product quality that most consumers expect now, and there’s a very high service level demanded now. These are goals that Lean practices enable if not necessarily guarantee.”

I think we can all agree that increased productivity, high quality, and improved customer service are laudable goals. Lean practices can indeed foster those objectives when things are running normally. Analysts who believe that companies can go “too lean,” are more worried about how lean practices adversely affect companies during crisis. McGuire, however, is talking about normal operating procedures. The article continues:

“So what’s the first step? Start with the people. You must have a ‘deep and honorable respect for your people,’ says McGuire. If not, they will drive the whole process – just not where you want it to go. Leadership is important. McGuire says the process can be so difficult that many companies may get a year or two into their project and then fail because they don’t have adequate leadership stature.”

I’m glad that McGuire started his discussion with people. Too often people are discussed after processes and technology; but, it is people that ultimately make processes and technologies work. The SCB staff next asked McGuire, “What’s the relevance of Lean programs in supply chain and logistics?”

“McGuire says Lean ‘looks’ at the value stream from the point of view of the customer. ‘It says that during the period between the decision to buy and the delivery of any goods, every activity either adds value to that value proposition or it doesn’t, and if not, it’s waste by definition and should probably be eliminated. Customers for the most part will look at the high cost of their transportation or logistics bill and will say that no longer is labor the difference between competitive and noncompetitive companies, it’s the approach to logistics. They favor those who can do it with few stops and delays, the best quality, and the best communications.'”

That’s where the tension arises and the Zone of Balanced Resilience comes into play. When natural or manmade disasters create disruptions in supply chains, lean supply chains can become brittle and customer service can be impacted. Resilient supply chains are optimized for disruptions so that customer service is much less affected. Customers will favor lean supply chains until disruptions occur (as happened a lot this past year) and then they elsewhere for more reliable goods or services. The article concludes:

“McGuire says over the past 10 years or so, the manufacturing companies that seem to be the best have three times the quality that the average ones possess, they are two to three times faster, they have communications skills that are double those of average competitors, and their people are more engaged. ‘So do they deserve the title of greatness?’ McGuire asks. ‘Perhaps not, but they certainly are better.'”

Better quality, faster service, and exceptional communications are not all necessarily traits associated with lean practices. All of them are traits associated with good supply chain visibility. That is why visibility is a much-discussed topic in supply chain circles. The next SupplyChainBrain article highlights a discussion the editorial staff had with Margo Ugarte of The Sustainability Consortium. [“Lean Concepts and Corporate Sustainability,” 3 January 2012] The article begins:

“Lean management is focused on reducing waste and sustainability is focused on lowering the use of resources, so the two concepts have a natural alignment, says Margo Ugarte of The Sustainability Consortium. Both of these movements draw from former initiatives, he says. ‘The quality movement in the 1980s established concepts from process quality to environmental impacts. Then with the lean movement, first in manufacturing and later in logistics, companies addressed the economic dimension of sustainability,’ he says.”

Lean practices do seem to be a natural partner for sustainability efforts since the only sustainability activities that will have lasting impacts are those for which a business case can be made. Ugarte, however, says that occasionally the objectives of lean and sustainability activities do come into conflict. The article continues:

“While both these initiatives deliver benefits, the benefits are not always straightforward, Ugarte says. For example, he notes that lean systems are, by design, meant to require less in the way of materials and resources. When applied to logistics, however, a lean program like just-in-time may require more intensive use of transportation. ‘To have a better customer service experience at the retail level, companies may need to devote more resources to distribution and infrastructure,’ he says. ‘It is a trade-off.'”

With transportation costs and disruptions caused by natural disasters apparently on the rise, some companies are reconsidering the value of just-in-time practices. Supply chain realignments may result in fewer conflicts between proponents of lean and sustainability principles. The article concludes:

“Ugarte disputes the idea that doing what is good for the environment is necessarily more expensive. He notes that manufacturers of laundry detergent have introduced products that are more environmentally friendly without increasing the cost to consumers. ‘It is possible to take costs out of the equation while producing products with better environmental characteristics,’ he says.”

I’m surprised that the cost of sustainability efforts remains a big issue. Most companies find that reducing waste, using less energy, and other such sustainable practices actually save them money as well as polish their public image. The final SCB article is drawn from an interview with Mike Loughrin of Transformance Advisors and focuses on implementing lean practices. [“Blueprint for Successful Lean Implementations,” 3 January 2012]

“Successfully implementing lean principles within a corporation requires distinct contributions from top-level, middle-level and front-line employees, says Mike Loughrin of Transformance Advisors. The challenge at the executive level is to know when to step in and help and when to stay out and let small teams work through the lean process and resulting cultural change, Loughrin says. An executive sponsor should make sure the project is defined correctly in terms of scope and goals and ensure that adequate resources are devoted to training and tools. Support should be demonstrated by having an executive at the kick-off and at occasional kaizen events.”

On that point, Loughrin and McGuire appear to be in total agreement. For those not familiar with the term “kaizen,” it is a Japanese business philosophy that involves continuous improvement of working practices, personal efficiency, and so forth. Any time that someone tries to change a corporate culture or business practice, good leadership is required. Niccolò Machiavelli, writing in The Prince, stated that change is difficult. He wrote:

“The reason is that all those who profit from the old order will be opposed to the innovator, whereas all those who might benefit from the new order are, at best, tepid supporters of him. This lukewarmness arises partly from the skeptical temper of men, who do not really believe in new things unless they have been seen to work well.”

To overcome this natural reluctance to change, “Loughrin says, executives should focus on the … milestones laid out in lean principles.”

“‘These milestones are a good time for the executive team to sit down and review what has been accomplished and to ask a lot of questions,’ he says. Middle management must deal with the skepticism of co-workers who may have gone through several similar strategies in the past, Loughrin says. Middle management has to get on board and then persuade others, ‘moving from a command-and-control mentality to more of a coaching mentality,’ says Loughrin. Middle managers also help prioritize areas of focus for the project. ‘Lean projects are not simply turning everybody loose in an organization to do some sort of process improvement. It is typically a structured approach, where teams are pulled together to work on priority items. Identifying those areas for improvement is where middle management can help,’ he says.”

It is a little ironic that middle management is seen as playing such a vital role when so many middle managers lost their jobs during this latest economic downturn. This is not the first time that I’ve read about the importance of middle managers and their importance in change leadership. Loughrin then moves down the organizational hierarchy to talk about front-line employees.

“For the front-line employee, the biggest challenge is deciding to invest in the program, says Loughrin. ‘Employees hear this big announcement and they wonder if it is real or just a cost and headcount reduction, especially if the company has a history of such programs.’ If they are convinced it is real, then they need to ask where they can help within their area of control, he says. The other challenge for front-line employees is in following through. ‘There typically are a lot of activities that can be done quickly and with great benefits. Front-line people tend to get excited about these but lose interest in the follow-through,’ says Loughrin. This phase is critical to long-term success because it is where workers tie up loose ends, document new procedures and put an audit program in place so that the gains are not lost, he says.”

If you follow McGuire’s advice and put people first, implementing lean practices will be much easier. Too often employees perceive change as either a criticism of their past performance or a threat to their future employment. By emphasizing people ahead of process, employees are more likely to become proponents of rather than obstacles to change.