Flexibility and transparency are two terms that are oft-mentioned during discussions about supply chains. In an interview with Daniel Schäfer, Martin Raab, head of supply chain management at Capgemini, asserted, “A lot of companies are currently thinking about ways to make their supply chains more transparent and flexible by further centralising them and digitalising the relevant information … as purchasing often adds up to 60 to 80 per cent of overall costs, this is something where you can save very much, very fast.” [“A stronger chain of command,” Financial Times, 11 October 2011] Saving money by becoming more efficient is obviously a desirable goal. Schäfer begins his article with the story of Barbara Kux, who, in late 2008, was hired by Siemens to head its newly created supply chain management organization. He continues:

“She soon discovered how badly her appointment had been needed. On evaluating Siemens’ supplier base, she was astonished to discover that Europe’s largest engineering company listed some of its 113,000 suppliers several times in its purchasing databases. The discovery laid bare the lack of transparency and the inefficiencies in the group’s decentralised purchasing system. Ms Kux’s experience will be familiar to many large and medium-sized industrial companies with gargantuan but cost-saving potential hidden in dispersed purchasing departments. While last year’s economic crisis forced companies to concentrate on short-term working capital reductions such as bringing down inventory levels, the recovery is prompting many to implement broader improvements in the supply chain. A recent global study by Capgemini, the consultancy, revealed that improvement of customer service and supply chain processes have replaced the economic downturn at the top of supply chain managers’ agenda.”

Clearly technology can play an important role in helping eliminate problems, like redundant vendor listings, and with making the supply chain purchasing process more transparent. Schäfer notes that “unlike the many plant closures or restructuring programmes initiated during the economic crisis, improvements in the supply chain do not take years to make a difference to profits.” He asserts that board-level appointments for supply chain professionals “is unusual in a country where responsibility for supply chains is seldom represented at such senior level”; but Germany need not be singled out in this regard. For more on this subject, read my post entitled S&OP: Supply Chain’s Foot in the Boardroom Door. Schäfer suggests that “Siemens’ approach is … a good example of supply chain reform.” He reports that Siemens based it reform on “three main pillars” — increased centralized procurement, increased low-cost sourcing, and a reduced number of suppliers. He continues:

“The first lever is to bundle a bigger amount of purchasing volume. … The biggest and fastest synergies can be reaped by centralizing purchasing of ‘indirect materials’ that are not directly used for making products. Siemens spends €11bn ($15bn) each year on such materials – from pencils to fork lifts – and it has recently appointed a senior executive responsible for centralizing these purchases. When it comes to direct materials, however, the process is much slower and more difficult. At the start, Siemens defined 20 material groups, such as plastics, cables, copper, castings, metal and mechanical parts, and it is now simplifying and harmonizing specifications for centralized purchasing.”

If you decide to transform from decentralized to centralized purchasing, expect some pushback from those who feel that they are losing control over their programs. You need to be able to make a business case that demonstrates that their profit margins will increase as a result of the change. An IBM study also stresses that creating value is important [“New rules for a new decade,” by Karen Butner, IBM Institute for Business Value, October 2010]. The report concludes:

“There is, and seemingly always has been, constant pressure for supply chain management and operations to create enterprise value. End-to-end supply chain cost and pipeline inventory optimization are predominant challenges, as well as the means for protecting margin and decreasing working capital.”

The greatest challenge in creating end-to-end enterprise value, Butner asserts, is not implementing the right technology but hiring the right people. She explains:

“Securing and deploying the right talent and skills for global operations remains a critical concern. The talent vacuum is most acutely felt in emerging markets, with nearly nine out of ten executives citing this as a challenge. The business risks associated with insufficient leadership talent is exposed in decreased cost efficiencies, inventory deployment, and in managing regional and local operations with partners. Managing risks and disruptions with global partners at each node is increasingly important. As supply chains become more complex and interdependent, managers must find a way to offset growing complexity with increased flexibility.”

When it comes to supply chain management, professionals must always keep in mind its three most important factors are: people, processes, and technology. Note that Butner specifically discusses the importance of flexibility and implies the importance of transparency (which is required to manage risks and disruptions with global partners). Turning to the second lever or pillar of Siemens’ supply chain transformation (i.e., increased low-cost sourcing), Schäfer writes:

“Bringing purchasing closer to Siemens’ markets is … an element of the second lever: a further push into low-cost sourcing by increasing the purchasing value from emerging markets by 5 percentage points to 25 per cent in the medium term. ‘We don’t call this low-cost sourcing but global value sourcing, because this is not only about costs but also about quality. There is a lot of value to be gained in places like China and India,’ Ms Kux says. But to achieve this, Siemens is not only working closely with local suppliers from emerging markets. It also offers partnerships to some of its smaller German suppliers to help them gain a foothold in China, since many of them lack the resources to do so on their own.”

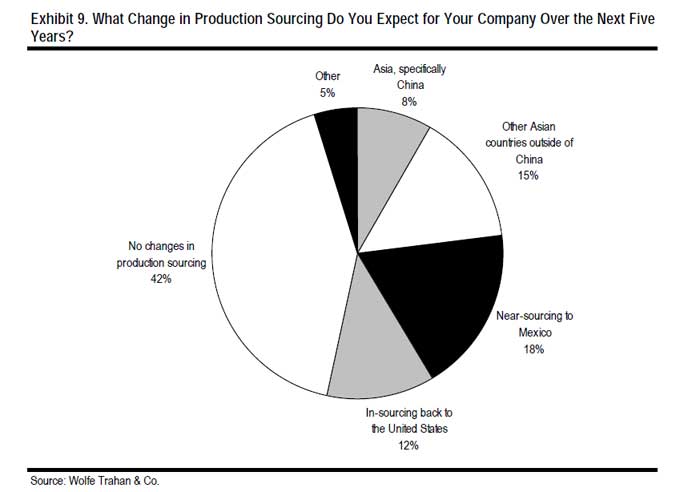

The editorial staff at Supply Chain Digest noted last year that most companies expected “no sourcing changes, [but of those companies that did expect changes], many were looking to Mexico and Asia outside of China.” [“Changes in Global Sourcing Plans,” 18 June 2010] The staff offered the following graphic to back up its assertions.

Supply chain analyst Bob Ferrari asserts that companies need flexible sourcing processes [“The Landscape for Sourcing in China and Other Countries is Once Again Changing,” Supply Chain Matters, 10 March 2011]. He writes:

“There are some important considerations that readers should ponder in these quickly changing forces. First, sourcing and supply chain planning teams will need to have more sophisticated analytical tools to analyze their options. … If there is one significant lesson that can be derived from sourcing decisions made in the past is that sourcing teams cannot just view direct labor costs as a sole determinant in any sourcing decision. There will always be a need to balance considerations for transportation with corresponding needs for servicing geographic fulfillment, including China itself. Another consideration is the speed of which the analysis, actual decision, and re-deployment takes place. The ability to shift sourcing quicker than the competition can be an important competitive advantage, while having flexible options may be another factor in assessing options and industry competitiveness factors.”

Turning to the final pillar of Siemens’ supply chain transformation strategy (i.e., reduced number of suppliers), Schäfer writes:

“While some suppliers receive such support, others have been dropped in an effort to streamline the supply chain. Ms Kux’s teams have been combing through Siemens’ supplier accounts in the past two years with the aim of reducing the number from 113,000 to about 90,000. The engineering group has also identified key suppliers for the future, with which it will work closely. ‘The future will not be Siemens against other companies but the best networks competing against each other. The company that will have the closest relationships with the best partners will have an immense and sustainable competitive advantage,’ Ms Kux says.”

I have noted in several past posts that I believe the real competition is between supply chains not between companies. Apparently Siemens is coming to believe that as well. How to deal with suppliers is an important part of any company’s business continuity/disaster recovery plans. To read more about how some company’s do this, read my post entitled Supply Chain Risk Management and Disaster Mitigation: Part 3. Martin Raab told Schäfer that supply chain reform “can improve operating profit margins by up to 10 percentage points. “In extreme examples,” he says, “a company can see its Ebit [earnings before interest and taxes] margin quadruple from 3 per cent to 13 per cent.” There is a caution here. Analysts like Bob Ferrari warn that companies should be careful about trying to make supply chains too lean because it is easy to cut through the fat and start cutting into the muscle needed to keep a supply robust enough to be flexible and adaptable. Supply chain disruptions caused by the catastrophe in Japan has a lot of companies wondering if they haven’t become a bit too lean when it come to sourcing and suppliers. Having said that, it is nevertheless looking at your supply chain to see if efficiencies are available that could help your company gain immediate and substantial savings.