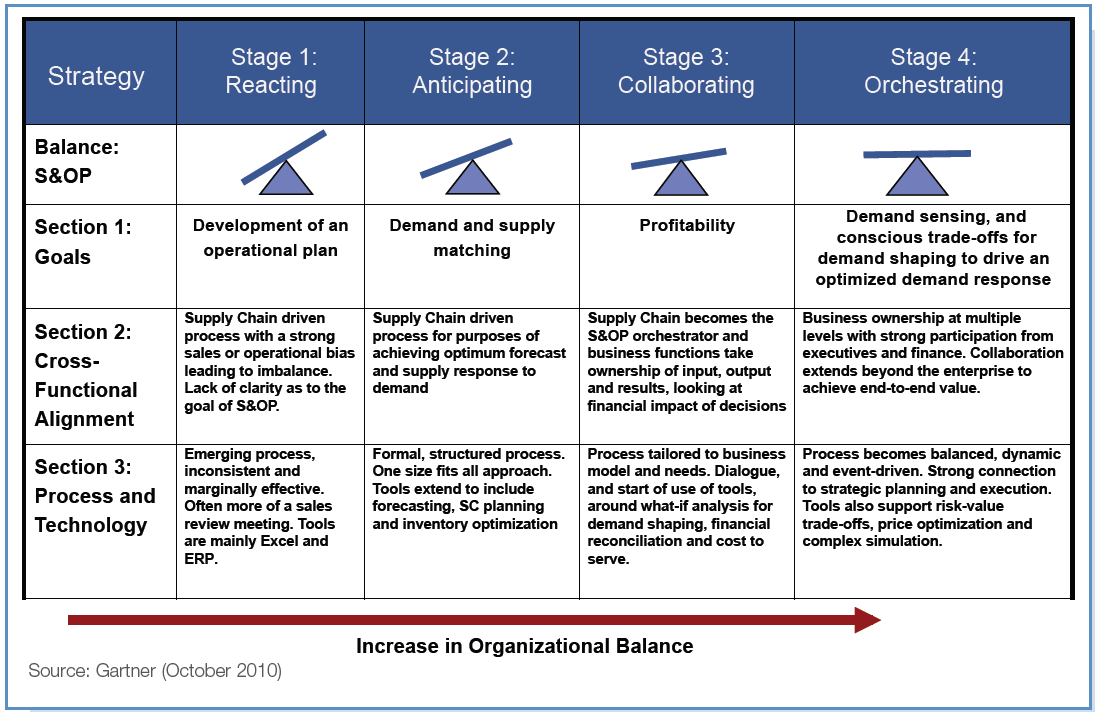

In a post entitled On the Bandwagon: Supply Chain Orchestration, among other discussed topics was Gartner’s Four-Stage Maturity Model. The model (shown in the figure below) defines maturity in terms of organizational balance. In Stage 1 (reacting), organizations are trying to figure out where they are headed with goal being the development of an operational plan. In Stage 2 (anticipating), organizations try to match supply with demand. Gartner analysts believe that the bulk of companies continue to fall within this stage. In Stage 3 (collaborating), organizations begin proactively working outside of corporate boundaries with other supply chain stakeholders. In the final stage of maturity, Stage 4 (orchestrating), companies go beyond collaboration and begin exercising control or significant influence on operations and standards throughout the supply chain. The below figure provides a good explanation of the four stages.

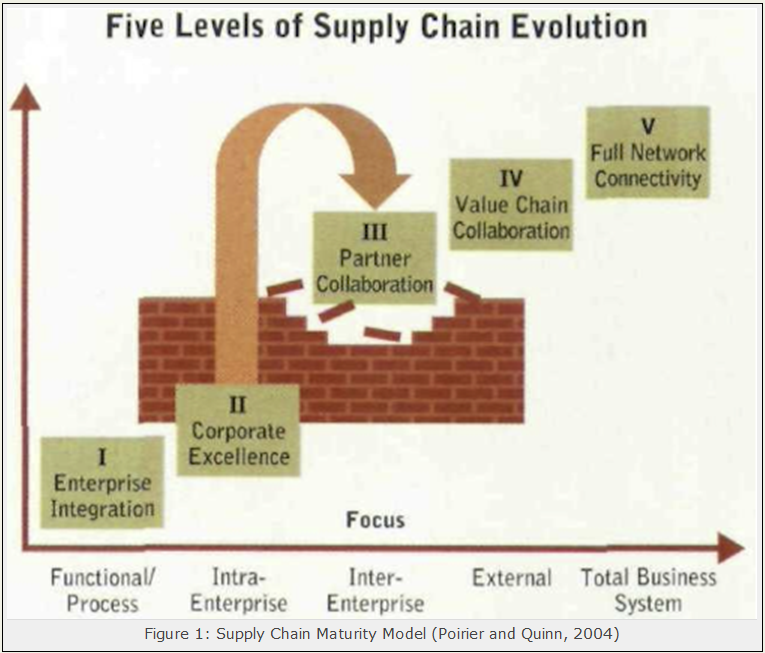

Gartner’s is not the only “maturity model” available. Charles C. Poirier and Francis J. Quinn offered a five-phase maturity model in their article entitled “How are we doing? A Survey of Supply Chain Progress” [Supply Chain Management Review, Vol. 8, Nº. 8, 2004, pp. 24-31]. The first phase of the Poirier and Quinn model involves enterprise integration that strives for corporate alignment. The second phase builds on the first to achieve corporate excellence. The focus of the first two phases is internal (i.e., intra-enterprise). In phase three organizations look externally to develop partner collaboration. In phase four, supply chain stakeholders work to create value chain collaboration (i.e., improved supply chain transparency and visibility). In the fifth and final phase, supply chain stakeholders achieve full network connectivity. In both the Gartner model and the Poirier and Quinn model, the greatest maturity challenge is achieving collaboration with supply chain partners. Gartner analysts insist this is why so many companies are stuck in Stage 2 and Poirier and Quinn show a wall at their third phase.

The fact that the two models both perceive a significant barrier at the collaboration phase of maturity should give supply chain professionals some reason to pause. To me it suggests that transformation rather evolution is required to break down the barrier. I’ve always associated evolutionary processes with a lack of speed that doesn’t seem to harmonize with the pace of today’s business activity. For example, Dictionary.com offers this definition of evolution: “a process of gradual, peaceful, progressive change or development.” Whereas, it defines transformation as: “change in form, appearance, nature, or character.” While I will admit that in the information age evolutionary processes are faster than they have been in past, I’m still not sure they are fast enough to keep pace with changes in the business landscape.

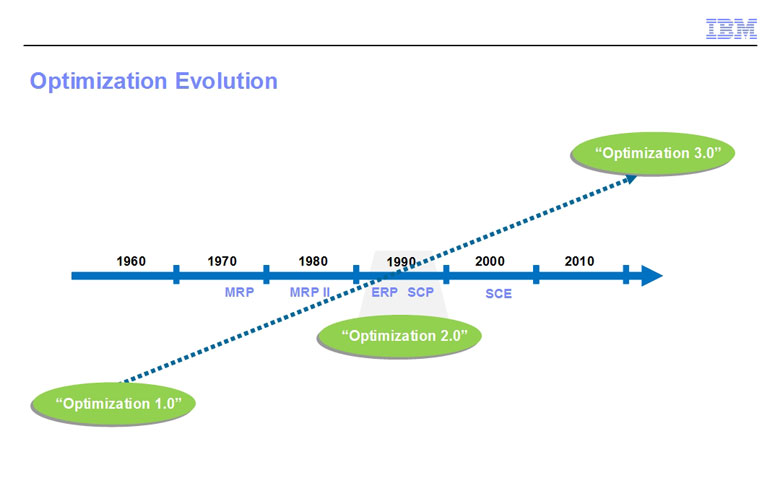

The article that started me thinking along these lines was written by the editorial staff at Supply Chain Digest [“The Evolution of Supply Chain Optimization Technology,” 7 April 2011] The staff asks the question, “Have we entered the Optimization 3.0 era?” They note that Thomas Dong of IBM, in a videocast interview, asserts that we are entering a new era. He claims that “tremendous advances in computing power are leading to significant new opportunities to leverage optimization technology in the supply chain.” The article continues:

“Dong said the first phase of optimization began in the late 1940s, when George Dantzig invented the Simplex method, the foundation of Linear Programming (LP) and more generally the discipline of mathematical optimization. Optimization provides a scientific means to determine the best decision across a set of constrained resources. The technology was first used in applications such as airline ‘yield management’ and optimizing telecommunications networks and routing. Optimization 2.0 was seen during the 1990s and beyond, as optimization tools were deployed to solve supply chain problems, such as supply chain network design and transportation planning. Optimization technology was used either as standalone tool sets companies themselves would adopt, or leveraged as embedded components in commercial software packages.”

In other words, the Optimization 1.0 lasted for 50 years while Optimization 2.0 lasted for only 30 years. This reflects an increase in the pace of “evolution”; but is it fast enough to keep pace with today’s business climate? The below graphic shows a linear progression that is probably not accurate (I suspect the straight line really curves upward).

The article concludes:

“Optimization 3.0 is happening now, Dong says, and is made possible by the huge advances in computing power. How much has it changed? Dong says that several years ago, increased computer horse power plus improved algorithms in the solvers had improved optimization performance more than 5 million times versus older technology. More advances have occurred since then. Why is this important? Because it allows companies to now use optimization technology to solve problems that simply weren’t feasible before, given the time it took to run the solvers. This greater performance will also allow creation of ‘real-time analytics’ for both decision support and automated action. This indeed is what Dong says is the future of supply chain technology. Case in point: An IBM semiconductor factory that reschedules itself every 5 minutes across numerous processes and variables, a scheduling frequency simply unimaginable with even second generation optimization technology. This is where we are headed.”

I agree with Dong that the world is changing rapidly and that we are now able “to solve problems that simply weren’t feasible before.” As President/CEO of a company that provides supply chain optimization solutions, I know that we are able to offer clients solutions that weren’t feasible even five years ago. That is how fast things are changing. Data that used to take weeks to collect and analyze will soon be able to be collected and analyzed in near-real-time — that’s transformational. Ronnie Davis, Managing Director of Customer Strategy at C.H. Robinson Worldwide, Inc., notes that “the advance of globalization and the need for greater operational agility are just two of the business trends that are raising the competitive stakes in most markets.” [“Are You Ready for a Smarter Supply Chain?” Logistics Viewpoints, 14 April 2011] He suggests that technology can help overcome the collaboration gap noted earlier. He writes:

“There are misalignments that are wider in both organizational and geographic terms that can frustrate more strategically ambitious projects. Aggregation of all transportation data through a single platform global TMS, for example, would help bridge the information gap for stakeholders in local, regional, and global geographies.”

Davis suggests that the big hurdle is not a lack of technology, but organizational culture (e.g., “divisive misalignments between functional and geographic silos in the organization”). Dan Gilmore, Editor-in-Chief of Supply Chain Digest, asserts, “I believe most of us can agree that the supply chain of the future is going to require very different skills sets among executives and mid-level managers than have been needed the very recent past.” [“Rebuilding Supply Chains for the Future,” 8 April 2011] Both Gilmore’s comment and the title of his article lead me to believe that he sees more transformation than evolution in the supply chain over the coming years. He continues:

“I think we may see even bigger shifts in the coming decade, largely … stemming from a variety of step-changes in supporting technology (cloud computing, real-time optimization, robotics, visibility) and the impact that will have on supply chain processes and even organizational structures.”

The bulk of Gilmore’s article is about a study by analysts at McKinsey & Company. He continues:

“McKinsey makes a bold statement right up front: ‘Many global supply chains are not equipped to cope with the world we are entering,’ McKinsey says. ‘Most were engineered, some brilliantly, to manage stable, high-volume production by capitalizing on labor-arbitrage opportunities available in China and other low-cost countries. But in a future when the relative attractiveness of manufacturing locations changes quickly—along with the ability to produce large volumes economically—such standard approaches can leave companies dangerously exposed.’ Here is a reality McKinsey observes and with which I completely agree: The world is changing rapidly, most noticeably with the rise of emerging economies across the globe, and not just China. That in turn will almost certainly lead to much higher levels of volatility in demand and supply, and greater levels of supply chain complexity than most of us have known to date. It makes perfect sense to argue that most supply chains as currently constructed are not well-suited to this new environment.”

In other words, most supply chains need to be transformed (i.e., “changed in form, appearance, nature, or character”). Gilmore goes on to describe McKinsey’s evidence of rapid change (e.g., “mobile-phone makers introduced 900 more varieties of handsets in 2009 than they did in 2000”) then states, “It is likely to get worse before it gets better.” He concludes:

“The upshot, McKinsey says, is that for ‘would-be architects of manufacturing and supply chain strategies there is a greater risk of making key decisions that become uneconomic as a result of forces beyond your control.’ I would add a complementary perspective: supply chain network design used to be mostly about the math (optimization) and the ability to drive the optimal solution through the supply chain in a timely manner. Increasingly, it is about how good a company’s assumptions are, and managing the trade-offs between cost and flexibility. You place your bets. The winning formula, McKinsey argues, is a two-pronged strategy:

“1. ‘Splintering’ traditional supply chains into smaller, nimbler ones better prepared to manage higher levels of complexity.

“2. Using supply chains as ‘hedges’ against uncertainty by reconfiguring manufacturing footprints to weather a range of potential outcomes. …

“At the end of the day, McKinsey says that to win in the global supply chain moving forward, companies need to be much better at segmenting their supply chains rather than taking a more universal approach, and that having production/supply chain capabilities in more places than is cost optimal in the short term may be cost optimal in the mid-term based on the added flexibility in this dynamic environment.”

I have written about McKinsey’s recommendations before (see my post entitled Building the Supply Chain of the Future). The bottom line is that supply chains don’t have the luxury of making a “gradual, peaceful, progressive change or development.” They must transform.