“The world has moved a step closer to a food price shock after the US government surprised traders by cutting stock forecasts for key crops,” reported the Financial Times [“World moves closer to food price shock, by Gregory Meyer, Javier Blas, and Jack Farchy, 12 January 2011]. Meyer and company report that corn and soyabean prices are the highest they have been in 30 months. Since the United States provides approximately half of the world’s corn supply, bad news for the U.S. is bad news for the world. The article continues:

“Dan Basse, president of AgResource, a Chicago-based forecaster, added: ‘There’s just no room for error any more. With any kind of weather problem in the upcoming growing season we will make new all-time highs in corn and soy, and to a lesser degree wheat futures.’ Agricultural traders and analysts warn that the latest revision to US and global stocks means there is no further room for weather problems. The crops in Argentina and Brazil, to be harvested soon, look fragile due to dryness.”

“Imperfect weather has collided with perfect food demand,” claims Gary Blumenthal, president and chief executive officer of World Perspectives, a Washington (D.C.) agricultural consultant. [“A Global Scare in Food Prices,” by Alan Bjerga, Bloomberg BusinessWeek, 6 January 2011]. How concerned are analysts? “The [UN’s] Food and Agricultural Organization said … that the world faces a ‘food price shock.'” [“U.N. agency warns of possible food crisis,” by Javier Blas, Washington Post, 6 January 2011]. Blas reports:

“The agency’s benchmark index of farm commodities prices shot up last month, exceeding the levels of the 2007-08 food crisis. The warning from the U.N. body comes as inflation is becoming an increasing economic and political challenge in developing countries, including China and India, and is starting to emerge as a potential problem in developed nations. Abdolreza Abbassian, a senior economist at the FAO in Rome, said that the increase was ‘alarming’ but that the situation was not yet a crisis similar to 2007-08, when food riots affected more than 30 poor countries, including Haiti, Bangladesh and Egypt.”

Although food riots have not yet affected dozens of countries, at least one country, Algeria, has suffered from riots over the rising cost of food [“Algerians riot over rising price of food,” by Roula Khalaf and Javier Blas, Financial Times, 6 January 2011]. Other countries, like India, may also be on the verge of unrest over rising food prices [“Economic fears as Indian food prices soar,” by Anjli Raval, Financial Times, 6 January 2011]. According to Raval, food prices in India are “rising at an annual rate of 18 per cent.” That’s a major concern because “millions still spend more than 50 per cent of their household income on food.” Returning to Blas’ Washington Post article, he reports:

“The FAO said that its food price index — a basket tracking the wholesale cost of commodities such as wheat, corn, rice, vegetable oils, dairy products, sugar and meat — jumped to 214.7 points, exceeding the peak of 213.5 set in June 2008. Abbassian said that agricultural commodities prices would probably rise further. ‘It will be foolish to assume this is the peak,’ he said. But the FAO and food aid agencies noted the relatively stable prices for rice, one of the two most important agricultural commodities for global food security. But the cost of wheat, the other critical staple, is rising quickly after poor harvests last year in Russia, Ukraine and elsewhere. Corn, meat and poultry prices are also increasing.”

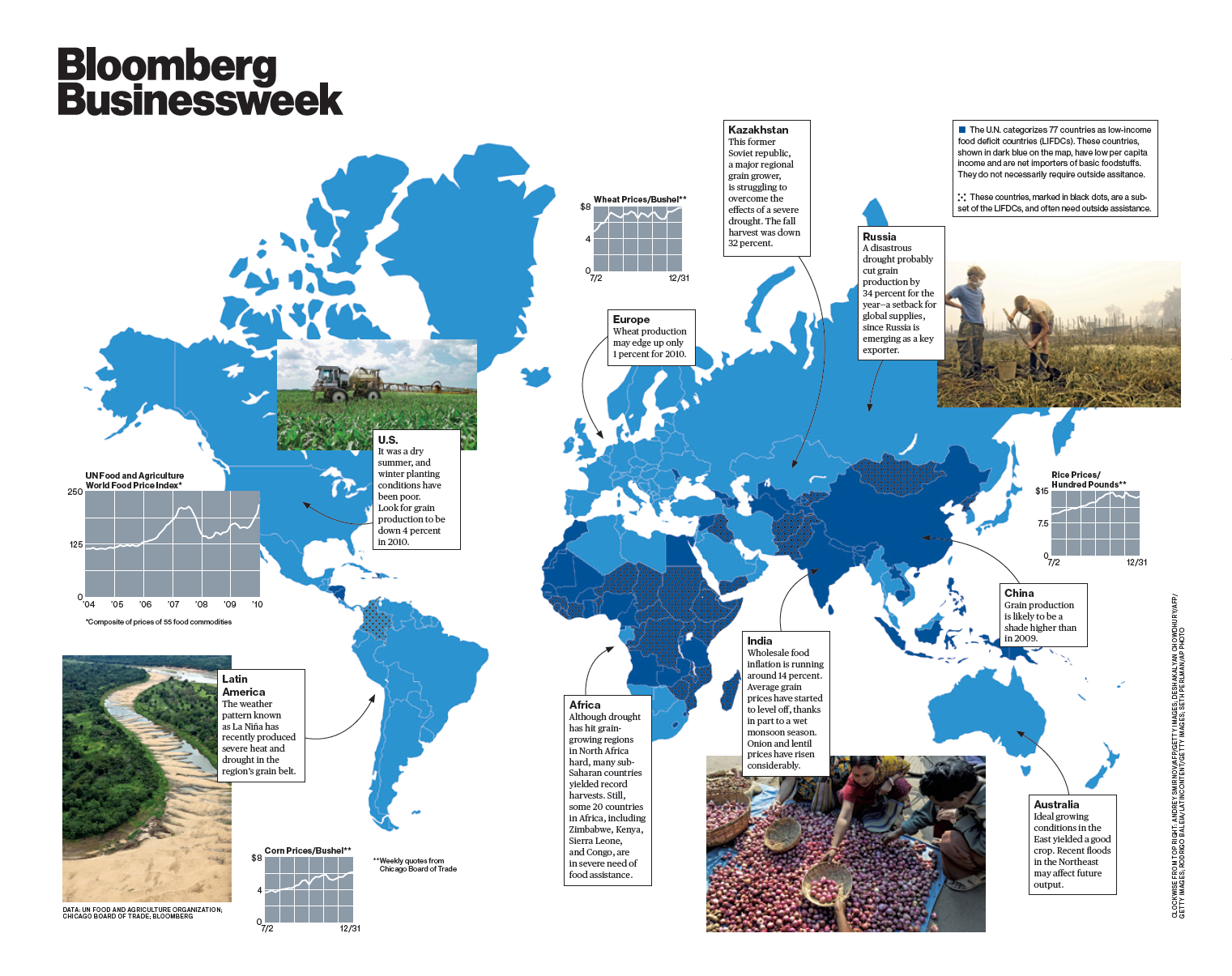

As Blas notes, weather hit wheat harvests harder than most other crops. Bloomberg BusinessWeek provided an excellent graphic that explains how weather affected crops around the world last year.

Blas reports that “agricultural officials and traders are worried that agricultural commodities prices could rise further as the weather phenomenon La Nina intensifies. The pattern usually brings dryness to key growing areas of the United States, Argentina and Brazil.” How bad could it get? Blas concludes:

“The Australian Bureau of Meteorology said that the current La Nina system would last at least three more months. Neil Plummer, a climatologist for the bureau in Melbourne, said the latest phenomenon looked set to be the most powerful since the mid-1970s, when droughts ravaged crops and pushed the world into the most extreme food crisis since World War II.”

That’s not good news for a world trying to claw its way out of recession. Rising food prices won’t just be a challenge for developing countries. “The increase in food costs will also hit developed economies, with companies from McDonald’s to Kraft raising retail prices.” [“Global food prices hit record high,” by Javier Blas, Financial Times, 5 January 2011]. Blas continues:

“Higher food prices are also boosting overall inflation, which is above the preferred targets of central banks in Europe. … The FAO food index is at its highest since the measure was first calculated in 1990.”

In addition to rising wheat, corn, and soyabean prices, other commodities that are driving up the Food Index are “sugar, whose price recently hit a 30-year high, oilseeds and meat.” I first discussed the current concern over rising food prices last November in a post entitled Fears Grow Concerning Possible Food Price Increases. In that post, I noted that the “grocery bill” for imported food commodities would top $1 trillion for only the second time in history. Blas believes that rising food prices make it all but certain that 2011 will top that figure for the second straight year and the third time in history. He reports:

“The rise of commodity prices makes it likely that the global food import bill will hit a record high in 2011, after topping $1,000bn last year for only the second time. In November, the FAO raised its 2010 forecast to $1,026bn, up almost 15 per cent from 2009 and within a whisker of a record high of $1,031bn set in 2008 during the food crisis. … The situation was aggravated when top producers such as Russia and Ukraine imposed export restrictions, prompting importers in the Middle East and North Africa to hoard supplies. The weakness of the US dollar, in which most food commodities are denominated, has also contributed to higher prices.”

Not all the news is bleak, Alex MacDonald and Liam Pleven report, “Despite challenging growing conditions in some major exporting nations, strong recent crops in many developing countries are helping governments and consumers manage the price spike. … Some African nations, … have seen healthy recent corn harvests.” [“Global Food-Price Index Hits Record,” Wall Street Journal, 3 January 2011]. Nevertheless, concerns are very real. The FAO has identified twenty African countries in crisis that still need outside food assistance. Obviously, all of these news reports have not escaped the notice of world governments. Kim Yeonhee reports that “the world’s biggest economies are working to find ways to bring down soaring food prices.” [“G20 to tackle food prices as countries reassure,” Reuters, 10 January 2011]. Kim continues:

“Policymakers are concerned that, if unchecked, rising food prices could stoke inflation, protectionism and unrest. … Rhee Chang-yong, who represents South Korea at the G20, said working-group talks were under way aimed at improving global cooperation to resolve food security problems. ‘France is emphasizing food security. As a former host country of G20, we would like to deal with the price volatility problem thoroughly,’ Rhee said. French President Nicolas Sarkozy has asked the World Bank to conduct urgent research on the impact of food prices, a source familiar with the matter said. French Prime Minister Francois Fillon said this week that one of France’s priorities at the G20, where it holds the rotating presidency, was to find a collective response to ‘excessive volatility’ in prices of food and energy. One concern is that high food prices could hit consumer spending in fast-growing emerging countries that are leading the revival of the global economy.”

None of the world’s leaders wants to see a repeat of the food riots that broke out in countries from Egypt to Haiti during the last food crisis. Nevertheless many of them believe that we are on the verge of unrest. Kim reports that “the U.N.’s World Food Program (WFP) … was feeding some 100 million people last year.” The hope is that food prices are nearing their acme and will begin to stabilize or decline. Kim reports:

“Robert Prior-Wandesforde, an economist at Credit Suisse in Singapore, said food commodity prices were unlikely to rise much further, barring weather catastrophes. ‘The estimated global and exporting countries’ stock-to-use ratios of both wheat and rice are considerably higher today than in 2007-08, making shortages and drastic export bans unlikely,’ he said in a report. But the London-based venture capital firm Emergent Asset Management, which holds swathes of land across southern Africa, still sees much more mileage in food prices. ‘The world is still in denial about food prices,’ its chief investment officer, David Murran, told Reuters. ‘If you look at demographics, if you look at production, if you look at the impact of climate change, then we are only at the beginning of this.'”

With record floods hitting Australia and La Nina intensifying, betting on good weather doesn’t seem very safe. Kim concludes:

“Many countries, including Brazil, India and China, have seen food inflation jump to double digit levels. Inflation rates accelerated across Latin America in December as costs spiked for food, increasing pressure on policymakers to raise interest rates. Prices rose sharply for Mexican tortillas and Chilean beef last month, while Brazilian bean costs surged over 2010. China has imposed price controls to try to ensure stable prices for consumers. … Ethiopia announced similar measures. Thailand, the world’s biggest rice exporter, sought to reassure the market, with Commerce Minister Porntiva Nakasai telling reporters it would maintain 2011 exports at 9 to 9.5 million tonnes after shipping 9 million in 2010. The Philippines, the world’s biggest buyer of rice, said it would cut its 2011 imports by at least half, compared with record purchases in 2010, further easing concerns of a tight rice market this year. Still, the head of the National Food Authority, which oversees rice imports, said it might increase its buffer stock to cover a minimum 40 days of demand, from 30 now. A senior food official in Bangladesh said it was worried about food security and had imported 250,000 tonnes of rice from Vietnam. In Indonesia, which has the world’s fourth-largest population, a fivefold rise in the price of chillies in the past year has helped drive overall inflation to near 7 percent. … In India, where onion prices have triggered protests in the past, prices have jumped after weather damaged the crop and officials have opened talks with Pakistan about resuming imports.”

We haven’t heard the last of this story or felt the last of the pain it will cause. On that point, I agree with David Murran. Whether public/private partnerships can work together to reduce extreme price volatility in the agricultural sector remains to be seen. Activity in the energy sector will also impact food prices. Rising fuel costs will put increased pressure on producers and distributors to pass those costs along to consumers.