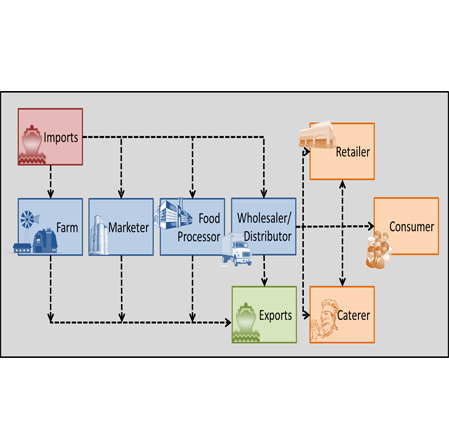

A couple of years ago, Daniel Dumke wrote, “The food supply chain satisfies one of the most basic Maslowian needs. Interruptions can quickly become [a] major crisis. Assessment and reactions to risks therefore seems to be a vital point.” [“Fragile Food Supply Chains: Reacting to Risks,” Supply Chain Risk Management, 5 March 2012] The focus of Dumke’s article was an article written by Samir Dani and Aman Deep entitled “Fragile food supply chains: reacting to risks.” [International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 01 October 2010] Dumke reported that In Dani’s and Deep’s article, “A typical foods supply chain consists of six echelons starting at the farmer. The second stage is usually an aggregator/marketer who provides the input for the processing facilities. The distribution stage starts with the wholesaler which delivers the product to the customer usually via a retail stage.” The current system would, thus, look like image below.

Dani and Deep identified two types of risks associated with the food supply chain. They are:

-

Type I: … Risks which are concerned with food safety, as well as maintaining a secure supply of food. These are differentiated on the basis of the responsibility and involvement of regulatory authorities. Food contamination is the most prominent of these risks and involves any incident which may constitute a public health emergency of domestic or international concern.

-

Type II: … All other risks which affect the supply chain but do not have a direct impact on food safety. The involvement of these types of risks is primarily the organisation and its direct supply chain. These risks include transportation strikes, loss of power, flooding, etc.

The “et cetera” at the end of the description of Type II risks deserves a lot more attention. For manufacturers, the et cetera involves both upstream risks (those associated with supply) and downstream risks (those associated with demand). Concerning upstream risks, analysts at The Strategic Sourcerer write, “Strategic sourcing is a dynamic proposition in any sector, but it can be particularly complex in the food industry. For manufacturers of packaged foods, for example, the number of suppliers required to produce a given product is often as extensive as the number of ingredients. [“Managing risks, costs is critical to food sourcing practices,” 9 January 2014] Andy Milner, procurement and supply chain director at WSH, insisted in an interview with Paul Snell, “We need the systems in place to mitigate any risk in our supply chain and that means working closely with suppliers to understand what drives their risk.” [“Moving up the food chain,” Supply Management, 12 December 2013] Getting systems in place that can monitor and report risk data in time to make a difference requires a high degree of collaboration between all stakeholders in the food value chain.

Last year at the Global Food Security Symposium organized by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Catherine Bertini, co-chair of the Global Agriculture Development Initiative, stated that “the Council sees three things as central to agricultural transformation: science, trade, and business.” [“Down with the Silos: Talk of Integration at Global Food Security Symposium,” Landscapes Blog for People, Food and Nature, 27 May 2013] Those “three things” must come together in such a way that all stakeholders understand what is happening now and could happen in the future should potential problems be detected. The Global Agriculture Development Initiative published a report around the same time as the symposium entitled “Advancing Global Food Security: The Power of Science, Trade and Business.” The report states:

“To equip the agriculture and food system to meet these challenges, [America must] make agricultural innovation a priority on its international and domestic agenda. … America’s public research system [must accept] a new mission: reinvent US and global agriculture so that it is far more productive, environmentally sustainable, nutritious, and resilient to setbacks through a focus on sustainable intensification. Sustainable intensification equips farmers with the innovations to:

- increase production of nutritious foods, bringing higher incomes to smallholder farmers,

- conserve land and water with efficient and prudent use of inputs,

- improve human health through accessible food that is nutritious,

- adapt to climate change,

- reduce environmental impact,

- reduce food waste along the supply chain.

The mission of sustainable intensification should draw on expertise from a broader array of scientific disciplines and be carried out by researchers and institutions — both public and private — in the United States, at international research centers, and at research institutes and universities in developing countries. Sustainable intensification must also include a focus on a broader set of crops to feed humanity. Corn, wheat, and rice now supply most of humanity’s calories. Yet it is becoming risky to have humanity depend so heavily on so few crops. The range of crop varieties grown around the world today is so narrow that a single plant disease can cause a food crisis. The tools and technologies to carry out sustainable intensification will be different depending on the location, but the principles are the same.”

A lot of different folks are going to have to get involved in the “mission of sustainable intensification” if both the quality and types of food being produced and consumed are going to meet the needs of the world’s burgeoning population. To learn about some of the food security strategies that can be employed, read my post entitled “Food Security Requires Implementing Complementary Strategies.” To read more about can be done in the area of food waste reduction, read my post entitled “Preventing and Mitigating Food Waste.” If the world is going to get serious about using alternative food sources to replace items currently being consumed, then ensuring that those alternative foods please the palates of those expected to eat them is essential. This means companies that supply spices and flavorings to the food industry are likely to play an even larger, more critical, role in the food industry in the years ahead. Bill Gates, co-founder and Chairman of Microsoft and co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, has written, “There’s quite a lot of interesting physics, chemistry and biology involved in how food tastes, how cooking changes its taste, and why we like some tastes and not others.” [“Bill Gates: Food Is Ripe for Innovation,” Mashable, 21 March 2013] I agree. It’s one of the reasons that work Enterra Solutions® is doing in the area of taste and flavors is so exciting and rewarding.

You really can’t talk about food security without at least mentioning the elephant in the room: climate change. Over the next few decades, climate patterns are likely to have major impact on what crop types can be grown in different areas and the yields that crops provide. The current drought affecting California, one of America’s most important food producing states, is just one example of how climate can have a major impact on food resilience. In a future post, I’ll discuss some of risk management efforts that are underway to help mitigate the impact of climate change and provide manufacturers with upstream visibility into their food supply chains.