One of the things developed countries have in common is good public education. No nation can achieve greatness without an educated population. An uncomfortable fact, however, is that education — even in developed countries — doesn’t provide a level playing field for students. Children living in poor neighborhoods often struggle to succeed in both school and life. Society’s goal should be to help these children succeed. Good schools are a necessary but not sufficient part of achieving that goal. Numerous studies have shown poverty and hunger can hinder educational achievement and schools are ill-equipped to deal with those challenges. A more holistic effort is required if society wants to help lift all its members to higher levels of achievement.

Poverty and Education

Journalist Lela Nargi (@LelaNargi) discusses how poverty and hunger affected her young life and how they currently impact millions of American children who are experiencing temporary, cyclical, or chronic food insecurity.[1] To demonstrate the unevenness of the playing field, Nargi reports, “USDA data for 2016 show 16.5 percent of households with children, and 31.6 percent of households with children headed by single women, experienced food insecurity, significantly higher than the 12.3 percent national average. The situation is compounded by race, as well: 22.5 percent of Black families and 18.5 percent of Hispanic families of all types experienced food insecurity in 2016, compared to 9.3 percent of white families.” America will struggle to maintain its place in the world if its children must worry about where their next meal is coming from rather than concentrating on how to excel in school. Jaimie Seaton (@JaimieSeaton) reports, “Being hungry has an enormous impact on a student’s ability to learn, so much so that Lucy Melcher, the director of advocacy and government relations for the nonprofit Share Our Strength, characterizes food as a basic school supply, akin to textbooks and pencils. Kids who go to school hungry may suffer an inability to concentrate and often fall behind academically. Hungry kids are more likely to miss school because of illness, and more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety, and develop behavioral problems as teenagers. They are more liable to drop out before graduation, which leads to lower paying jobs and a greater probability of being food insecure adults. There’s a lot of potential being squandered because kids are going to school hungry and the ramifications go beyond a growling stomach.”[2]

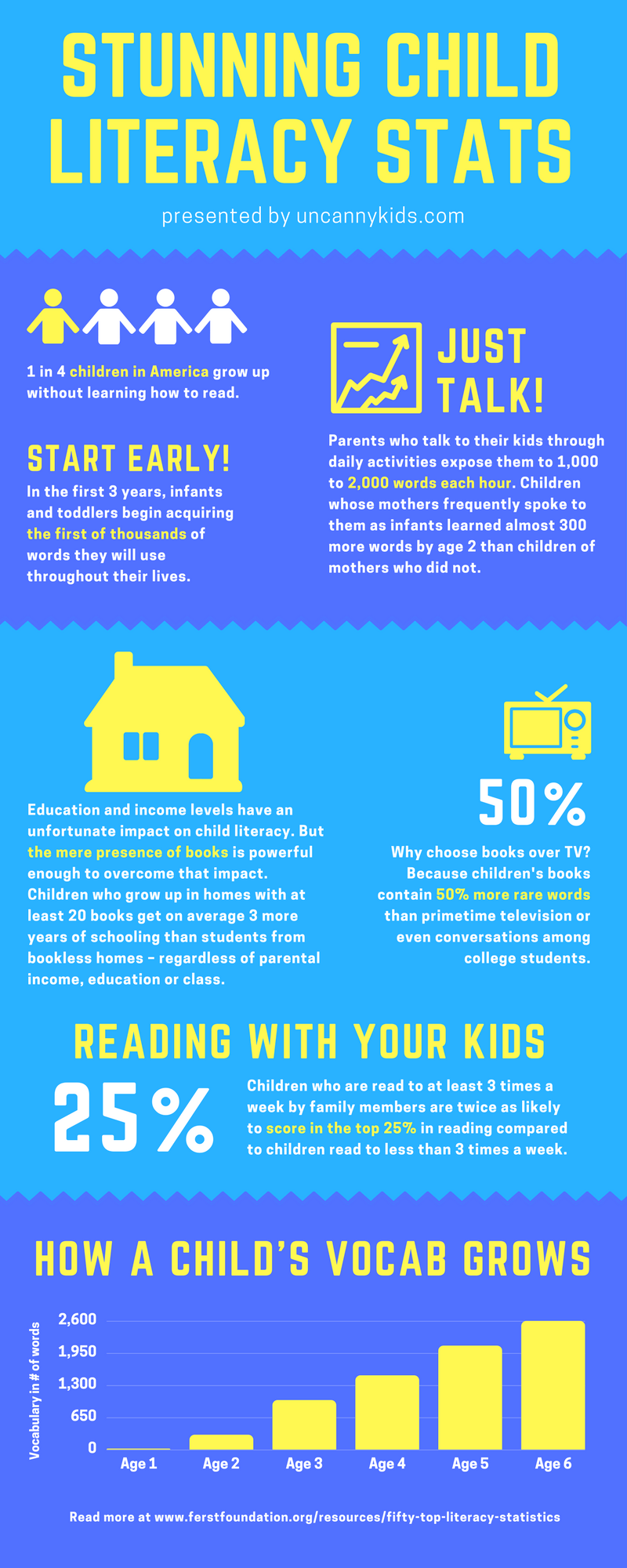

Of course, being hungry is only one drawback associated with poverty. Elizabeth Mann (@elizkmann), a Fellow in Governance Studies at Brooking’s Brown Center on Education Policy, writes, “Two decades ago, researchers Betty Hart and Todd Risley revealed a particularly stark difference in the experiences of toddlers with different income levels. As Hart and Risley described it, low-income infants hear many fewer words per day than their middle- and high-income peers, totaling to a 30-million-word difference by age three. They coined this discrepancy ‘the word gap.’ Hart and Risley also found that students who had heard fewer words as toddlers correlated with worse performance on tests of vocabulary and language development years later.”[3] Writing about follow-on research to that Stanford study, Motoko Rich reports, “The new research by Anne Fernald, a psychologist at Stanford University, which was published in Developmental Science [in 2013], showed that at 18 months children from wealthier homes could identify pictures of simple words they knew — ‘dog’ or ‘ball’ — much faster than children from low-income families. By age 2, the study found, affluent children had learned 30 percent more words in the intervening months than the children from low-income homes.”[4] As the following infographic shows, reading skills are also impacted by poverty.

Find more education infographics on e-Learning Infographics

William F. Tate (@DeanWFTate), vice provost for graduate education at Washington University in St. Louis, observes children are often locked into poverty because of circumstances.[5] He explains, “If people don’t have the skill set to participate and contribute, then you basically reinforce a cycle across generations, and they’re never going to be able to jump into the growth of the economy. From a place point of view, people and families tend to reside over time in the same areas, and this just reinforces itself over the decades.” As noted above, verbal and reading skills are critical to helping children succeed at school. Tate asserts science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) skills are essential for them to succeed at life. He explains:

“Everything that matters in our society is counted, put in an algorithm. People are weighing cost-benefit and how to max out, whether it’s the health care system or whether we’re talking about social media algorithms used to push information to people. You have to be thinking about the world in this way. Those who understand how we mathematize are actually in a better position to consume and to navigate their life course. … Statistical and computational skills are foundational to where we’re headed as a society, too.”

I agree with Tate on that point. That’s why I and a few colleagues, founded The Project for STEM Competitiveness — a non-profit organization whose mission is to bring outcomes-measured STEM education to underrepresented populations. This approach can demonstrate to students that STEM subjects can be fun and applicable in their lives. I also understand, however, children are unlikely to see the fun and importance of STEM subjects if their stomachs are rumbling and the words they hear are unfamiliar.

Mark R. Rank, a professor of social welfare at Washington University, reports, “A majority of Americans will experience poverty during their lives, and America’s rate of poverty consistently ranks at or near the top in international comparisons. Rather than slashing anti-poverty programs, the fiscally prudent question to ask is: How much does this high rate of poverty cost our nation in dollars and cents? Clearly, poverty extracts a heavy toll upon those who fall into its ranks, particularly children. Countless studies have demonstrated the physical and psychological health costs for children experiencing poverty.”[6] Rank, along with his colleague, Michael McLaughlin, “determined that childhood poverty cost the nation $1.03 trillion in 2015. This number represented 5.4 percent of the G.D.P. Impoverished children grow up possessing fewer skills and are thus less able to contribute to the productivity of the economy. They are also more likely to experience frequent health care problems and to engage in crime. These costs are borne by the children themselves, but ultimately by the wider society as well. An even clearer way of gauging the magnitude of these costs is to compare their total with the total amount of federal spending in 2015. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal government spent $3.7 trillion that year, meaning that the annual cost of childhood poverty represented 28 percent of the entire federal budget. Equally important, we calculated what the cost savings would be for poverty reduction. Our analysis indicated that for each dollar spent on reducing childhood poverty, the country would save at least $7 with respect to the economic costs of poverty.”

Summary

Poverty reduction should be an issue embraced across the political spectrum. Reducing poverty means the government will spend less on social programs in the years ahead as children finally break free of poverty’s grasp and add their contributions to the economy. We know greatness and genius can be found in unlikely places. We need to give every child a chance at greatness by improving their educational experience. Given an opportunity, children lifted out of poverty could invent products that will improve our lives or found companies that will employ future generations of children. America’s future, like the future of other countries, rests in the fortunes of our children.

Footnotes

[1] Lela Nargi, “What Children Understand About Food Insecurity,” Civil Eats, 26 March 2018.

[2] Jaimie Seaton, “Reading, writing and hunger: More than 13 million kids in this country go to school hungry,” The Washington Post, 9 March 2017.

[3] Elizabeth Mann, “The ‘word gap’ and one city’s plan to close it,” The Brookings Institution, 10 July 2017.

[4] Motoko Rich, “Language-Gap Study Bolsters a Push for Pre-K,” New York Times, 21 October 2013.

[5] Jim Mitchell, “STEM challenge: Are demography and geography destiny?” The Dallas Morning News, 18 April 2018.

[6] Mark R. Rank, “The Cost of Keeping Children Poor,” The New York Times, 15 April 2018.