Robert J. Bowman, from SupplyChainBrain, wonders aloud if sales and operations planning (S&OP) is setting itself up to be another enterprise resource planning (ERP) nightmare. [“What Is This Thing Called S&OP?” 25 April 2011] Recalling some of the nightmarish scenarios that early ERP adapters went through, he writes, “ERP became a cautionary tale about the perils of buying big software packages without fully understanding what was required to make them work in a ‘legacy’ environment.” He continues:

“I wonder whether sales and operations planning is the new ERP. Not because an S&OP project is doomed to fail – plenty of companies have reported good results from embracing the concept. The reason that ERP comes to mind is that the successful implementation of S&OP software seems to require just as radical a transformation in a company’s business processes. More so, even, if you consider that S&OP affects nearly every part of the supply chain.”

Dan Gilmore, Editor-in-Chief of Supply Chain Digest, goes even further. He writes that S&OP “is on a path to supersede the supply chain.” [“What We See in S&OP,” 15 April 2011] Gilmore doesn’t explain what he means exactly, but it is clear that S&OP represents a sea change in how businesses conduct planning. That being the case, Bowman asks, “So what is S&OP?” He continues:

“Most definitions are lengthy and crammed with buzzwords, but it boils down to a means by which companies can align production with actual demand, through the merging of tactical and strategic planning methods across any number of organizational silos. S&OP takes into account product design, raw materials, manufacturing capacity, labor, finance, distribution, marketing, sales and customer service. (Sounds suspiciously like the Supply Chain Council’s SCOR model, which breaks down into the stages of Plan, Source, Make, Deliver and Return.) The basic concept isn’t that difficult to grasp, although consultants like to confuse the issue by constantly inventing new acronyms that purport to describe even greater levels of organizational integration.”

Supply chain analyst Lora Cecere agrees with Bowman that there is too much embellishment of S&OP going on by vendors trying to sell their products. She believes “that the term S&OP is letter perfect.” [“S&OP: Letter Perfect,” Supply Chain Shaman, 7 June 2010] Gilmore agrees with both Bowman and Cecere that too many vendors are trying to invent their own terms in an attempt to differentiate their offerings from those of other vendors. He writes, “One of the interesting S&OP trends is a battle of nomenclature, but there is some deeper meaning behind that terminology skirmish. For some time but now gaining steam recently, many are pushing the term ‘Integrated Business Planning’ or IBP as the correct name and concept for the process.” Gilmore tries to square the circle this way:

“S&OP really has its roots in [the] supply chain, and tends to have a great deal of its focus on the important exercise of balancing supply and demand plans. IBP, on the other hand, is really about creating alignment to meet the company’s financial goals. Supply-demand balancing is a necessary but not sufficient component of that goal. What is critical – and often left out of ‘traditional’ S&OP – is aligning the supply and demand plans more tightly with the company’s financial plan and goals.”

Gilmore’s and Bowman’s emphasis on corporate alignment and how IBP can help break down corporate silos are important points. Cecere seems to believe, however, that IBP may be goal whose attainment is a bit too much to hope for considering how few companies have mastered S&OP. She believes that “S&OP has risen in importance,” but asserts that its implementation has been imperfect. Bowman seems to agree. He is willing to stipulate that “that a formal S&OP process is itself a desirable goal,” but fears that consultants will try to find the next “big thing” even though S&OP is “far from ready to be supplanted by a trendier concept, given that so few companies have yet to adopt it in full.” He continues:

“S&OP [is] … a series of processes that should be implemented in phases. The management consultancy Oliver Wight talks about the need for a detailed review of product, demand and supply before combining it all under a comprehensive management business review. MIT has described a four-stage maturity model which outlines progressive improvements in numerous areas, including the frequency and nature of meetings, the degree of integration among processes, and way in which software applications are deployed. And Nari Viswanathan of Aberdeen Group has shown how the progress of implementation varies widely across businesses, with only about a third of those surveyed having managed to integrate financial planning and budgeting with S&OP.”

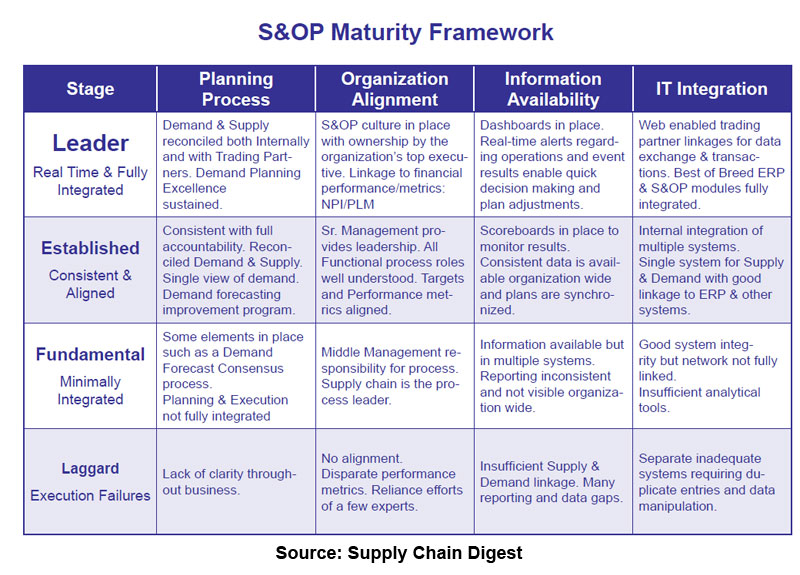

Gilmore writes, “There is probably no area of supply chain that has seen more maturity models than S&OP.” Nevertheless, he admits that he and his colleagues, with help from Bob Nardone, former supply chain executive at Unilever, couldn’t help themselves and constructed a maturity model of their own (shown below). The four-by-four matrix underscores Bowman’s point that S&OP is “a series of processes that should be implemented in phases.”

To see Gartner’s S&OP-related maturity model, read my post entitled Supply Chain Evolution and Transformation. Bowman reports that back in 2007 “less than half of surveyed companies were doing supply and capacity planning as part of their S&OP programs.” Fortunately, Cecere indicates that things have improved. She reports, “Today, three out of five projects for Supply Chain Planning (SCP) software are driven by a person with a S&OP-specific title.” Bowman continues:

“According to the software vendor Kinaxis, modern-day S&OP must contain at least four key capabilities: scenario management, by which a company can explore multiple ‘what-if’ situations; financial measures, including cash-to-cash cycle, gross margin and economic value-add; early alerting, when key performance indicators exceed tolerance levels, and management by exception, with the ability to identify the precise cause of an out-of-tolerance condition. Kinaxis ‘thought leader’ Trevor Miles views quick responsiveness as a critical corrective to the errors that plague any demand forecast. Speaking at the IE Group’s recent High-Tech Forecasting & Planning Innovation conference in San Francisco, he noted that forecast errors by the top consumer packaged goods companies range between 19 and 43 percent. S&OP can help to offset that shocking gap by enabling them to plan for variance.”

Click on this link to download a copy of the Kinaxis e-book that “provides an overview of what an advanced S&OP process should look like and what it takes to get there.” To learn more about what analysts are saying about forecasting, read yesterday’s post entitled How Important is Supply Chain Forecasting? To learn more about scenario management, read my post entitled Examining the “What Ifs” in Life.

The final point that Bowman makes is that companies need to recognize the difference between tactical and strategic planning. He writes:

“Mike Groesch, vice president of S&OP with NCR Corp., said the process is an invaluable tool in a configure-to-order environment – yet another technique for coping with demand variability. The problem, he said, is that too many companies – including, until recently, NCR – fail to separate their tactical and strategic efforts. The first stage of S&OP is basic execution – ‘the weekly grind,’ as Groesch put it. The people who handle order management and fulfillment can’t also be responsible for the long-term aspects of real S&OP, with its monthly and quarterly planning cycles. In Groesch’s words, sales and operations execution (S&OE) is the ‘foglights,’ while S&OP represents ‘the headlights [that shine] further.’ Don’t make the mistake of conflating the two.”

Lori Smith, from Kinaxis, believes that S&OP is like a corporate GPS. [“The Four Keys to S&OP Effectiveness,” The 21st Century Supply Chain, 28 April 2011] She writes:

“Imagine a pilot flying from New York to Los Angeles at night without any navigation systems or instruments to measure his location, wind speed, or altitude. Instead, every two hours he checks the stars with a sextant, extracts data from the flight recorder about his throttle settings, and draws in the plane’s likely location on a map. What are the chances of that pilot actually getting to LA? Can he arrive on any predictable timetable? You’ll likely agree his chances are slim to none. A modern pilot embarks with a general flight plan, but then monitors a continuous readout of key metrics, which he uses to make numerous small course corrections to help arrive at the proper destination on schedule. It’s the same for business. Every company needs a sophisticated navigation system to help determine where you are going, where you have been, when you are off course, and how to get back on course. Successful S&OP provides a navigation system and a set of instruments for piloting a company through our turbulent times.”

Bowman asserts that a company needs “someone at the top to drive the [S&OP] effort and cut through the fog of acronyms and marketing hype. If you don’t have that, perhaps you ought to be in a business where demand is predictable and customers are married to you forever.” Dan Gilmore claims that he once “heard a senior Dell official say that ‘S&OP is a religion’ at the company.” That may be taking devotion to S&OP a bit far. S&OP is a tool not an altar at which businesses must worship. Things change and that will hold true for S&OP as well. If you let S&OP become a sacred cow, you’ll find out that when changes do come killing the sacred cow will be difficult. Judging by the current state of S&OP implementation described by Bowman and Cecere, S&OP will be around for a long time before it morphs into something closer to IBP as described by Gilmore.