Earlier this year, Dan Gilmore, Editor-in-Chief of Supply Chain Digest, was asked to give a speech in Columbus, OH (I’m assuming at The Ohio State University), about the supply chain. Before the speech, he wrote that the exact topic was unclear but he assumed they wanted him to answer some of these questions: “What is logistics? What is its role in the grand scheme of things? How is Ohio impacted for good or bad by logistics? What thoughts do I have for the students relative to logistics careers?” [“What to Tell Students and Bureaucrats about Logistics?” 11 February 2011] I don’t know how long he was given for his speech, but the best 8-minute explanation of what is involved in supply chain management that I’ve heard is found in the first video of a 12-part series produced by the Department of Supply Chain Management at Arizona State University’s W.P. Carey School of Business.

If you took the time to watch the video, you have to admit that it was extremely well done. You have to give credit to Professor Eddie Davila, who wrote, produced, and hosted the series. I first mentioned this series of videos in a post entitled Can Supply Chains Save the World? Gilmore tells us his thoughts on the subject as he was trying to put his speech together. He writes:

“The term ‘logistics’ is sometimes used almost synonymously with the term ‘supply chain,’ and though in truth the industry hasn’t done a great job clearly defining the differences, most would consider logistics a subset of supply chain management, a discipline that is primarily about the physical movement of goods, whereas supply chain is about more than that.”

In the video, Davila recommends thinking about “managing the chain of supplies” as a way of understanding how broad the subject of supply chain management really is. As Gilmore correctly points out, moving things (logistics) is only a subset of all of the things that a supply chain professional needs to think about. Gilmore continues:

“One standard definition of SCM is that it is about the synchronized movement of materials, information and cash. That’s not bad, but it sounds very ‘logisticy’ doesn’t it? Materials movement. Many others have tried to create ‘models’ that identify various core processes of the supply chain. A famous one is the SCOR model, which says that the SCM core processes are ‘Plan, Source, Make, Deliver, Return.’ That’s not bad, and there are other similar ones – but it is not enough to really understand supply chain management.”

I agree with Gilmore that there are a lot of definitions about the supply chain. In a post entitled Defining the Supply Chain, I noted that trying to pin down one of them is difficult because “a manufacturer like Dell, that eschews traditional brick-and-mortar retail stores, has a very different supply chain model than a more traditional retailer like Walmart.” One of the best macro-definitions I offered in that post came from David Blanchard’s book entitled Supply Chain Management: Best Practices. In that book, he wrote:

“A supply chain, boiled down to its basic elements, is the sequence of events and processes that take a product from dirt to dirt. … A supply chain, in other words, extends from the ultimate supplier or source … to the ultimate customer. … So whether you’re talking about an Intel semiconductor that begins its life as a grain of sand or a Ford Explorer that ends its life in a junkyard where its remaining usable components (tires, seat belts, bumpers) are sold as parts, everything that happens in between those ‘dirt to dirt’ milestones encompasses some aspect of the supply chain.”

Gilmore likes the definition provided by Dr. John Gattorna, who defines the supply chain as “a combination of processes, functions, activities, relationships and pathways along which products, services, information, and financial transactions move in and between enterprises, in both directions.” Gilmore continues:

“That’s comprehensive, for sure, and pretty accurate. But maybe too much so. It sounds like SCM is the almost the entire business, doesn’t it? We used to just call all that ‘operations.’ And indeed, supply chain is a substantial part of a business, especially for firms that deal primarily or substantially in physical goods. In a manufacturing company, the supply chain can be directly involved in up to 80% of the enterprise’s total cost structure. 60% or more is commonplace. What supply chain connotes that ‘operations’ often does not is that it involves multiple enterprises. The ‘chain,’ if you will, but really more accurately the ‘network.'”

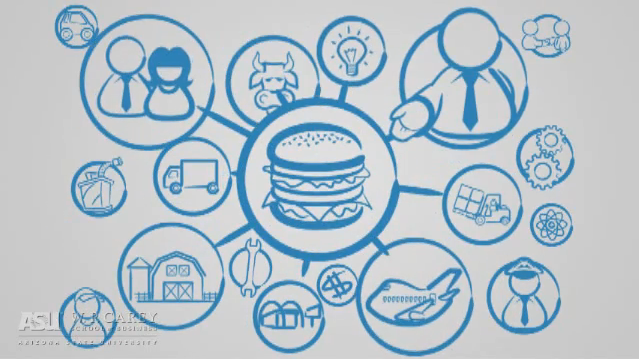

Although the ASU video doesn’t mention “networks” per se, it clearly depicts a network rather than a chain during the discussion. For example, the image below, taken from the above video, shows the “supply chain” for “manufacturing” a hamburger. That looks more like a network than chain to me.

Gilmore goes on to discuss his vision of a supply network (what is commonly referred to as a demand driven supply chain). He writes:

“My favorite SCM concept goes back more than two decades, when someone defined the future vision of the supply chain as getting to the stage where, when a sweater is sold in Peoria, somewhere in New Zealand a sheep is shorn. But it doesn’t work like that yet today.”

Although I suspect that Gilmore is preaching to the choir (i.e., those who read Supply Chain Digest), he goes on to discuss the importance of the supply chain. He writes:

“Supply chain and logistics are incredibly important functions in others ways. Logistics costs as a percent of US gross domestic product was getting close to 10% before the recession and financial crisis arrived in late 2008. That’s a big number, and actually doesn’t capture costs related to manufacturing, sourcing operations and more. The true percent is much higher. There are other changes going on that are further increasing the importance of supply chain and logistics – and globalization is at the top of the list. That goes literally both directions. As we in the US and elsewhere increasing move to low cost countries to source finished goods and components, the cost of the product itself may go down, but the cost and complexity of the supporting logistics goes way up. It takes real skill to design and execute this kind of physical product movement in a timely way at a cost that is acceptable. Those that don’t do global logistics well find those low unit product costs don’t deliver much if anything to the bottom line in the end. That discussion just focuses on the ‘source’ and ‘make’ processes – think also about the ‘deliver.’ Emerging markets are where most everyone believes much of the growth will be, and with good reason. There are more than 190 countries in the world, and many dozens of them now represent markets that companies didn’t much care about until recently but now very much do.”

To learn more about why companies are focusing on emerging market countries, read my post entitled The Emerging Global Middle Class. Gilmore points out that emerging market countries “have their own culture, legal and political environment, physical infrastructure, talent pools, level of logistics maturity, and more.” As a result, he asserts that “a company needs to design a unique supply chain for each.” For multinational corporations, Gilmore insists that in the future they could “be running 100+ supply chains across the globe. Companies like Coke and Procter & Gamble already are, or close to it.” Getting back to the talk he was about to deliver, Gilmore points out that for students this is good news; since it “means right now and for many years going forward, demand for good supply chain talent is going to outstrip the supply.” He continues:

“That’s not just me saying that – it’s something my friend David MacEachern, one of the industry’s leading supply chain executive recruiters at Spencer Stuart, has said repeatedly over the past few years. Sure, the opportunities dried up some during the recession, as they did for everything. But a recent survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers found that 48% of US companies plan to snap up supply chain and logistics grads in 2011. Fortune magazine was surprised by this. Those of us in the profession were not. Salaries and bonuses for top supply chain executives are often now 2-3 times what they were a just a few years ago. But new skill sets are also required today than were in earlier eras. Part of it is the need for global supply chain competencies, but it goes well beyond that. Successful supply chain managers – those with a chance at reaching executive levels – need an increasingly broad set of skills beyond the ‘engineering and technical’ talents that used to be the most in demand. Now you need more strong general business skills, to be able to effectively communicate with and influence peers in other functional disciplines, to understand ‘supply chain finance,’ to be able to work at the board level, and much more.”

The fact that Gilmore talks about supply chain professionals working “at the board level” is also an encouraging sign. That hasn’t always been the case (see my post entitled S&OP: Supply Chain’s Foot in the Boardroom Door). Gilmore writes that as bright as the picture is, “it’s not all good news with supply chain careers.” He explains:

“Nearly every business today is under pressure to constantly reduce costs, and if supply chain represents 70% or something of a company’s cost basis, that is where the CEO and CFO are going to look. There are many in the profession who feel beat up from the relentless cost cutting pressure they face. The culture around this can vary quite a bit from company to company, but it’s pretty ubiquitous in one form or another. It’s just part of the job. Also to date, a supply chain career has rarely led to the top of the organization chart. We have very few examples of a supply chain exec becoming a company CEO, but there are exceptions, such as recently retired WalMart CEO Lee Scott, who began his career there in logistics. Some people believe the ‘Chief Supply Chain Officer’ may become the new ‘COO.’ We’ll see, but I do believe we will gradually see more SCM professionals make it to the top.”

The purpose of the ASU videos is to help potential students select supply chain management as a career (i.e., a career “that makes all of your childhood supply chains dreams come true”). Gilmore asserts that, in the past, many supply chain professionals, including him, “found their way there sort of by accident.” Because of programs like those at ASU and at the University of Tennessee [“University of Tennessee Establishes Comprehensive Global Supply Chain Institute,” Supply Chain Brain, 18 April 2011], students are now choosing supply chain management as a career. Gilmore admits there has been an increase in “supply chain degree programs at both the graduate and undergraduate level.” He believes, however, that the message needs to reach below the level of higher education. He writes:

“If 1 out of 100 high school guidance counselors know much about supply chain careers or university programs, I would be surprised. Logistics competitiveness is key to country economic competitiveness. The less we collectively spend on logistics in the US, the more our companies can spend on say R&D or to meet or exceed market price requirements. A recent study by the World Bank ranked the US 15th globally in logistics competitiveness, mostly behind countries in Europe. You could legitimately argue that the US should have been ranked higher, but it is a fact that, as just one example. leading Asian ports are several times more efficient than the best in the US. There is some general consensus that we need to invest more in US logistics infrastructure, but in what specific areas, how much, and where the funding will come from (such as a higher diesel fuel tax) is far from clear, even among leading supply chain thinkers. These will be big economic questions. Today, we don’t have good cost/benefit frameworks to help do the analysis.”

Since Enterra Solutions® does work in the ports and harbors sector, helping port operators become more efficient and secure are some of our goals. With bigger ships being built to take advantage of enlarged Panama Canal, greater efficiency is an imperative. Gilmore concludes:

“I have covered a lot of ground here, but there is so much more that could be said. Supply chain and logistics matter now more than ever, and that trend will continue at multiple levels: nationally, the business attractiveness of a state, a company’s market and financial success, individual opportunities and careers, and more. Today, most companies – but not all – get this. National and state governments? Hard to answer Yes on that, though there are many exceptions. For the students in the audience: like everything, a supply chain career has its pros and cons, but if you are good, the demand for your talent will be about as strong as any profession – and better than most. It’s a path I didn’t exactly choose, but it has worked out very well for me and many I know. I am glad it found me.”

If you just happen to be a student looking for a career, I would take the time to view the entire ASU series on the subject.

- Module 2: Buy It: Managing Supply

- Module 3: Make It: Manufacturing and Operations

- Module 4: Move It: Transportation and Logistics

- Module 5: Sell it & Service It: Retail Considerations

- Module 6: Supply Chain Integration

- Module 7: Global Supply Chain Management

- Module 8: Socially Responsible Supply Chain Management

- Module 9: Business Processes

- Module 10: Measuring Performance

- Module 11: Quality Management

- Module 12: Supply Chains and Information Technology