Noted supply chain analyst Lora Cecere flies a lot. I suspect that most of her flights are uneventful. Occasionally, however, things go wrong and Lora starts thinking about customer service (or the lack of it). When she was still working with AMR, Lora wrote a post about customer service entitled “What is customer service?” [Connecting the Dots, 30 July 2009]. In that post, she said that most executives she interviews claim they want to improve customer service but when asked what customer service means they simply give her a blank stare. She concludes, “I would argue that most have not stepped back to assess what … customer service [should] mean to their organization.”

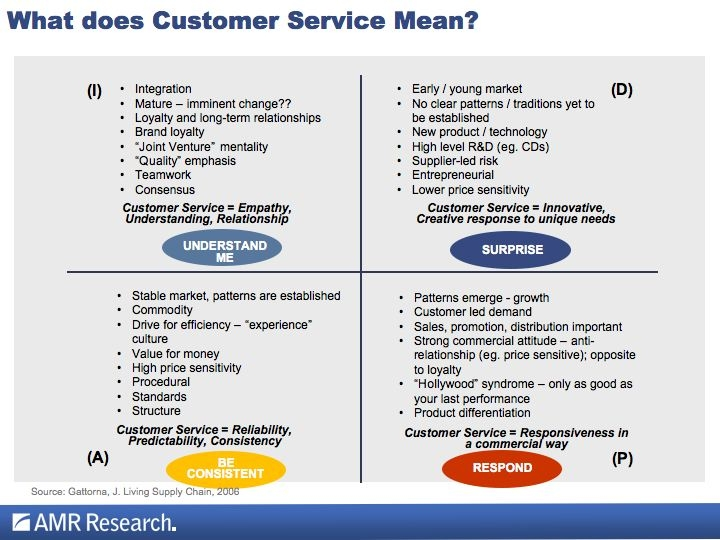

Although you may think that customer service should be easily defined, Dr. John Gattorna, who is generally regarded as a Global thought leader in the Supply Chain Management, pointed out in his book Living Supply Chains that customer service means different things to customers depending on the type of business a company is in. In her post, Lora included a graphic from Professor Gattorna’s book that explains the differences.

Gattorna argues that what defines customer service depends on the underlying logic that is required to align a company’s activities with its operating environment. He asserts that companies are influenced by four “behavioral forces or logics”: Integration (I); Development (D); Administration (A); and Producer (P). As you can see from the chart, customers working with companies in the Development sector understand that they are dealing with start-ups, new technologies, etc. That’s why customers want to be pleasantly surprised by the service they receive. On the other end of the spectrum are companies in the Administration sector. These companies are very mature and operate in a stable environment. Customers working with these companies expect consistent treatment. You get the idea. Lora wrote this post while experiencing an unpleasant flight. She concluded, “Unfortunately, the airline has not figured out that I want CONSISTENCY. When I purchase a ticket, the airline should be ALL about reliability, predictability, and consistency. I do not want drama or fodder for a blog post.”

Fast forward from July 2009 to October 2010. During another unpleasant airline experience (she was about to miss her own birthday party because of delayed flights), Lora once again turns to the subject of customer service [“Can you Listen?” Supply Chain Shaman, 1 October 2010]. She writes, “In most companies, the group named customer service is mis-named. While the department is named ‘customer service,’ it really is a group of order takers.” She argues that if customer service groups fail to listen to their customers they simply can’t provide service. Companies that fail to listen, she further argues, are in for a rude awakening as social commerce takes flight. Lora provides an example of how a company can be stung when it fails to listen. She writes:

“Meet Dooce. When Heather Armstrong (@dooce)’s Whirlpool washing machine broke down, she called the Maytag repair man. When her calls to the customer service, and the subsequent visit by the repairman did not resolve the problem, she turned to twitter. Dooce advised her legion of over a million twitter followers to not buy Maytag. Her first tweet: ‘DO NOT EVER BUY A MAYTAG’, was followed in three minutes by a tweet of ‘I repeat: OUR MAYTAG EXPERIENCE HAS BEEN A NIGHTMARE’, was followed by ‘Have I mentioned what a nightmare our experience was with Maytag?’ arrived into the inbox of the newly formed Whirlpool’s customer service team it was the team’s 12th tweet. The incident made national news. Dooce had an impact. Today, the Whirlpool customer service team has been transformed to listen to the customer. They meet weekly cross functionally – marketing, customer service, field service and product management—to listen the voice of the customer from Twitter and Facebook.”

Lora warns, “Unfortunately, … 80% of the companies I [have] interviewed … are not ready for Dooce. Most are unaware that danger lurks ahead. They are unaware that they can now have meaningful consumer dialogue.” Although she provides a couple of examples of companies that seem to have learned the lesson, Lora nevertheless concludes, “The use of social technologies as listening posts gives us the ability to listen, but few are up to the task.”

P.V. Kannan, the co-founder of 24/7 Customer, agrees with Lora that today’s customer service model is basically broken [“24/7 Customers’ P.V. Kannan: ‘The State of Affairs in Customer Service Is Broken’,” India Knowledge@Wharton, 23 September 2010]. I think most consumers would agree with Kannan’s first point, which is: “There’s no single owner for a consumer.” He explains:

“If you are a subscriber of a cable provider, there’s not a single stop where you can go and say, ‘I need this fixed.’ Typically the method that has evolved in the past few years is to call their 800-number. Or let’s consider a mobile phone operator. You can buy the phone and activate the service in a real store. But if you try to ask a question beyond that, they’ll say: ‘Please dial the 800-number.’ The issue is fragmented and companies have made it ‘your problem.’ Today in 2010, consumers are voting with their clicks; they would prefer to interact with a company’s customer service division via the Internet.”

I doubt there is anyone reading this post who hasn’t experienced “customer service runaround” while trying to get help using a company’s hotline. While such experiences provide grist for stand-up comics, they provide only frustration for customers. One of my employees received that kind of runaround when he tried to get his Magellan portable GPS working again. Magellan customer service eventually threw up its hands and recommended trading in the old model for a new one using their “Customer Loyalty” program. When he called the number provided and asked about the “Customer Loyalty” special, he learned that Magellan was offering to sell him a new portable GPS (with trade-in) for about $10 more than he could buy the same unit from Amazon.com (without a trade-in). So much for rewarding loyalty. Needless to say, he now owns a TomTom GPS system. When the person interviewing Kannan, asked, “Why do you think big companies underestimate the power of customer service?” He responded:

“In each industry, the power of competitive forces dictates their behavior. Beyond that, leaders at companies carry their own personal ethos and values. Barring a few exceptions, such as Nordstrom in retail or Southwest Airlines in travel, the mean isn’t that admirable. … Dealing with customers is either made into a ‘customer service problem’ or how customers feel is made into a ‘marketing & loyalty problem.’ Once a company starts thinking like that, it’s all downhill. Most companies are only motivated to tackle customer service when they see their competition doing so — and winning. They match to that expectation and that’s pretty much it. Today, with the reach of social media, from blogs to Twitter, ideas and information are able to proliferate. Most companies surely recognize this, but usually their first instinct is to ask, ‘How can I use this channel to sell more stuff to my consumer base?’ There is merit to this; we can’t argue with that. But at the same time, most miss the opportunity to also use these networks to create better channels to interact with their customers. At the end of the day, companies that are passionate about engaging with customers actually spend a lot less dealing with customers than companies that try to avoid those interactions.”

On that latter point, Cecere and Kannan are in total agreement. Since most companies don’t “get it,” Kannan’s interviewer presses the subject, “Let’s focus on the two networks that gather the most attention today — Facebook and Twitter. How can brands use them to deliver a new type of customer service, where they can actually predict and analyze consumer behavior?” Kannan responds:

“When we started analyzing Twitter streams of various companies and brands, we found that, in general, the negative-to-positive ratio of tweets related to an account was roughly four-to-one. A while back, if a customer had a bad experience, he could complain to seven friends. Nowadays, that complaint could touch 70 or 700 friends almost instantaneously. Furthermore, as a customer, I would like to communicate my complaints in the quickest, most direct manner possible and have the conversations public. Typically, brands fail to capture this opportunity and instead make a labyrinth of touch points for the customer to navigate. … My core message is that brands need to step back and find the best ways in which to have an honest dialogue with customers. I don’t think customers care if their messes are handled through blogs, or Twitter, etc. They just want the problem fixed.”

Kannan goes on to argue that companies have no excuse for not offering better customer service. He continues:

“The days of 800-number and process charts and passing the customer around and around are over. In all this madness, however, there are some methods, and 24/7 Customer tries to figure those methods out and help companies better predict what types of customer service inquiries they should expect. Let’s use the example of buying a smartphone. In the first five days, most inquiries relate to phone settings, emails and other basic items. Then when the first bill is due, the questions shift to inquiries about promotions, rates, charges, and so forth. Predictably, every month, if 100 subscribers sign up, 66 people actually call with these two sets of questions. Companies fielding these requests act surprised, but in reality, they are entirely predictable. At 24/7 Customer, [we] create models for companies whereby they actively integrate these predictive models into [their] customer service offering. Consumer expectations are changing. We live in a world where Google tells you what you have typed wrong. Google tells you that you might be looking for this. It’s a free service. Facebook and LinkedIn tell you these might be your friends, and both are free. It’s a shame that companies to which you pay $50, $100, $200 a month refuse to even acknowledge you.”

Consumers would certainly like to believe Kannan when he claims “the days of 800-number and process charts and passing the customer around and around are over.” But as Lora’s experiences highlight, customer service still has a long way to go. Hey companies, are you listening?