We would all like to believe that we have the potential for greatness. Greatness, of course, is a subjective measure. How, for example, would you rate a mother or a father who successfully raises children and provides them with a strong ethical foundation and a moral compass that helps them lead useful and productive lives? Most of us would probably say that they did a great job raising their children; but, does that make them great in the eyes of the world? My point is, greatness may not be all that it is cracked up to be. This article, however, is about education and learning — not parenting per se. Parents would like their children to succeed at school because they understand that a good education opens the doors to opportunities that would otherwise remain shut. I’m convinced that one of the best things that parents (and teachers) can do to help children is to teach them how to persevere. In a previous article, I discussed the work of Angela Duckworth (@angeladuckw), a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania. The premise of her work is that even smart kids can get discouraged and, without training and encouragement, they can give up on certain subjects. She wants children to learn what she calls, “Grit.” For her work, Duckworth received a 2013 MacArthur Fellowship (i.e., a “genius” grant). Below is a video from the MacArthur website in which Duckworth explains her work.

Tovia Smith reports, “Around the nation, schools are beginning to see grit as key to students’ success — and just as important to teach as reading and math.”[1] Smith continues:

“Experts define grit as persistence, determination and resilience; it’s that je ne sais quoi that drives one kid to practice trumpet or study Spanish for hours — or years — on end, while another quits after the first setback. … But can grit be taught? ‘I hope so,’ says Duckworth, ‘but I don’t think we have enough evidence to know with certainty that we can do so.’ Part of the problem is figuring out how to assess grit. Duckworth says ‘these things are really hard to measure with fidelity.’ Even so, many schools around the nation have embarked on their own experiments — they see the promise of the concept as too great to wait. … One way to make kids more tenacious, the thinking goes, is to show them how grit has been important to the success of others, and how mistakes and failures are normal parts of learning — not reasons to quit.”

Frankly, I find the arguments for at least trying to teach kids how to persevere quite compelling. Duckworth, however, doesn’t push the notion that excessive practice can overcome all obstacles. That’s a concept made popular by Malcolm Gladwell and Robert Greene, who insist that, with enough practice at something, you can become a virtuoso or a genius in that area. To read more on that topic, see my post entitled “Innovation: Geniuses and Perseverers.” However, even the most talented child might get discouraged to learn that he won’t achieve greatness unless they reach the 10,000-hour or 20,000-hour mark of dedication. To reach the 10,000-hour mark, someone must dedicate 90-minutes of their life every day for 20 years (obviously, either the daily commitment or lifetime commitment must be doubled to reach the 20,000-hour mark). To a young student, that might look as difficult as eating an elephant. Gladwell’s concepts have received a lot of attention since they were first published and, according to Rob Nightingale, “This 10,000-Hour Rule has become a platitude for life-long learners, lifestyle designers, and self-improvement bloggers. This is despite increasing evidence showing that the 10,000-Hour Rule is grossly inaccurate.”[2]

For one thing, Nightingale notes, “Gladwell failed to adequately distinguish between the quantity of hours spent practicing, and the quality of that practice.” Nightingale believes that Tim Ferriss (@tferriss), a modern renaissance man, has a better approach to learning that greatly reduces the amount of time needed to learn a subject, but it still requires grit. Ferriss tackled the subject of rapid skill acquisition in his book The Four-Hour Chef. Nightingale writes:

“Throughout his book Ferriss introduced millions of readers to the idea of meta-learning. That is, the learning about learning. Once we understand how our brain and body learns, we can create a far more efficient learning regimen. In fact, Ferriss, during a SXSWi presentation claimed: ‘I believe you can become world-class in any skill in 6 months or less.’ This may or may not be an exaggeration, but what Ferriss is emphasizing here is the quality of practice over the quantity. But even if the real figure is two-years, not six-months, it’s a gargantuan improvement on Gladwell’s hideous promise of 10,000 hours.”

Nightingale goes on to discuss a few ways that all individuals (not just young students) can improve how they learn. The first way is to create a feedback loop. He explains:

“By creating a feedback loop (or a smart feedback loop), you’re creating a way to more accurately spot your errors and identify potential improvements that are having an effect on your learning. One study conducted at Brunel University, UK explains: ‘A feedback loop [provides] … the necessary information for adaptive measures to achieve the desired levels of teaching and learning objectives.’ Acquiring the necessary information to get to a desired objective is precisely what rapid skill acquisition is about. It’s about finding out exactly what you need to change to reach your goal more quickly.”

We’ve all heard the old saw, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” Unknowingly, many of us fall into that trap believing we are practicing the right way or studying the right way. A feedback loop can help us break the cycle of doing the same thing and expecting different (or better) results.

The second way that Nightingale suggests we can improve our learning (and the one most pertinent to this article) is through deliberate practice. Although he insists that deliberate practice isn’t the whole story, he does believe that practice is very important. In deliberate practice, a person concentrates on mastering the sub-skills that constitute a portion of the overall skill one wants to learn. For example, if a person wants to improve their skill as a basketball player, they have to concentrate on sub-skills like passing, dribbling, jumping, and shooting. Running up and down a basketball court for hours without a specific goal in mind won’t achieve the desired effect. Nightingale points to the work of a couple of academics to support his point about deliberate practice. The first academic is Anders Ericsson, a Professor of Psychology at Florida State University, who published an article entitled “The Influence of Experience and Deliberate Practice on the Development of Superior Expert Performance.” In that paper, he wrote, ““The effects of mere experience differ greatly from those of Deliberate Practice, where individuals concentrate on actively trying to go beyond their current abilities.” Nightingale adds, “Unsurprisingly, Deliberate Practice is hard. Ericsson found that elite athletes, writers, and musicians could only sustain the concentration needed for Deliberate Practice for relatively short periods of time. Their concentration on very specific skills, however, ensured they continued to improve and perform at the top of their game.”

The second academic referenced by Nightingale is Cal Newport, an Assistant Professor of Computer Science at Georgetown University. Newport insists that successful people develop “the ability to focus intensely on cognitively demanding tasks; a skill he calls ‘deep work’.” Quoting Newport, Nightingale writes, ““By choosing a specific aim (i.e. becoming an expert WordPress programmer), you can clearly see the sub-skills that are important to master in order to help you achieve this aim — PHP, CSS, etc. Each of these individual sub-skills, of course, can be broken down into further sub-sub-skills. By deliberately focusing on mastering each of these sub-sub-skills individually, you can become an expert WordPress programmer.” Both Ericsson and Newport stress that practice is important; which is why teaching students how to persevere in the face of challenges is essential to their success.

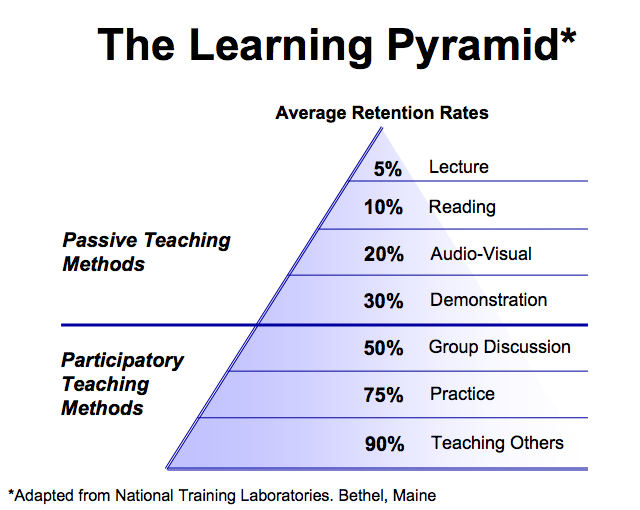

The last thing that Nightingale suggests can be done to improve learning is to become a teacher. He explains, “The idea of learning through teaching isn’t new. But after a certain amount of research, the National Training Laboratories felt confident enough to release The Learning Pyramid. This is a simple diagram showing the very rough retention rates to be expected through various forms of teaching. The pyramid has its opponents, but for many, it remains a reliable guideline. As you can see, the passive learning approaches offer relatively low levels of retention.”

I’m a big believer in participatory teaching methods. That’s why I, along with a few colleagues, founded The Project for STEM Competitiveness — to help get a project-based, problem-solving approach into schools near where we live. We firmly believe that by showing students how STEM subjects can help them solve real-world problems using participatory methods they will begin to appreciate the opportunities that STEM skills open for them. If parents and teachers would concentrate on teaching children how to persevere in face the challenges, they would go a long ways towards insuring that the children under their care are successful in life. They may never achieve greatness in the eyes of the world, but they can become successful and contributing members of society.

Footnotes

[1] Tovia Smith, “Does Teaching Kids To Get ‘Gritty’ Help Them Get Ahead?” NPR, 17 March 2014.

[2] Rob Nightingale, “The 10,000 Hour Rule Is Wrong. How to Really Master a Skill,” Makeuseof, December 2015.