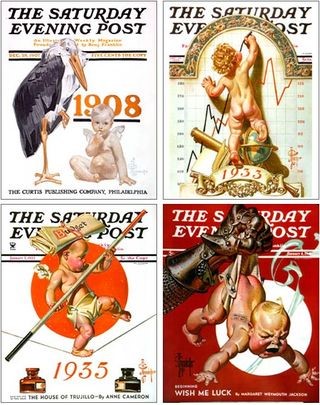

As each new year approaches, the ending year is pictured as an old man and the new year is pictured as a young baby. The attached image of some old Saturday Evening Post covers shows that the practice of depicting the new year as a baby has been around for a long time. Over the past couple of months, there have been a number of articles about babies and fertility rates and what the numbers might mean for the future. For example, back in October, The Economist noted that “astonishing falls in the fertility rate are bringing with them big benefits” [“Falling Fertility,” 31 October 2009 print issue]. The article begins where many such discussions about demographics begin, with the 18th century prediction of Thomas Malthus that by 19th century the world’s food supply would be inadequate for the burgeoning global population. The article notes that Malthus got it wrong “because industrialization swept through what is now the developed world, fertility fell sharply, first in France, then in Britain, then throughout Europe and America. When people got richer, families got smaller; and as families got smaller, people got richer.” The article notes that this same phenomenon is now sweeping through many developing countries. It continues:

As each new year approaches, the ending year is pictured as an old man and the new year is pictured as a young baby. The attached image of some old Saturday Evening Post covers shows that the practice of depicting the new year as a baby has been around for a long time. Over the past couple of months, there have been a number of articles about babies and fertility rates and what the numbers might mean for the future. For example, back in October, The Economist noted that “astonishing falls in the fertility rate are bringing with them big benefits” [“Falling Fertility,” 31 October 2009 print issue]. The article begins where many such discussions about demographics begin, with the 18th century prediction of Thomas Malthus that by 19th century the world’s food supply would be inadequate for the burgeoning global population. The article notes that Malthus got it wrong “because industrialization swept through what is now the developed world, fertility fell sharply, first in France, then in Britain, then throughout Europe and America. When people got richer, families got smaller; and as families got smaller, people got richer.” The article notes that this same phenomenon is now sweeping through many developing countries. It continues:

“Fertility is falling and families are shrinking in places — such as Brazil, Indonesia, and even parts of India—that people think of as teeming with children. … The fertility rate of half the world is now 2.1 or less — the magic number that is consistent with a stable population and is usually called ‘the replacement rate of fertility’. Sometime between 2020 and 2050 the world’s fertility rate will fall below the global replacement rate.”

In about 40 years, the global population is predicted to top out around 9 billion people. That’s still a lot; but a level or decreasing population base will allow for better planning and more sustainable development. The article reports:

“Today’s fall in fertility is both very large and very fast. Poor countries are racing through the same demographic transition as rich ones, starting at an earlier stage of development and moving more quickly. The transition from a rate of five to that of two, which took 130 years to happen in Britain—from 1800 to 1930—took just 20 years—from 1965 to 1985—in South Korea. Mothers in developing countries today can expect to have three children. Their mothers had six. In some countries the speed of decline in the fertility rate has been astonishing. In Iran, it dropped from seven in 1984 to 1.9 in 2006—and to just 1.5 in Tehran. That is about as fast as social change can happen.”

The Economist sees the falling fertility rate as a good thing for a number of reasons.

“Falling fertility in poor and middle-income societies is a boon in and of itself. It means that, for the first time, the majority of mothers are having the number of children they want, which seems to be—as best one can judge—two. (China is an exception: its fall in fertility has been coerced.) It is also a boon in what it represents, which is greater security for billions of vulnerable people. Subsistence farmers, who live off their harvest and risk falling victim to rapine or drought, can depend only on themselves and their children. For them, a family of eight may be the only insurance against disaster. But for the new middle classes of China, India or Brazil, with factory jobs, cars and bank accounts, the problems of extreme insecurity lie in the past. For them, a child may be a joy, a liability or an accident—but not an insurance policy. And falling fertility is a boon for what it makes possible, which is economic growth. Demography used to be thought of as neutral for growth. But that was because, until the 1990s, there were few developing countries with records of declining fertility and rising incomes. Now there are dozens and they show that as countries move from large families and poverty into wealth and ageing they pass through a Goldilocks period: a generation or two in which fertility is neither too high nor too low and in which there are few dependent children, few dependent grandparents—and a bulge of adults in the middle who, if conditions are right, make the factories hum. For countries in demographic transition, the fall to replacement fertility is a unique and precious opportunity.”

The article concedes that not everyone agrees with its assessment.

“Nonsense, say Malthus’s heirs. All this misses the point: there are too many people for the Earth’s fragile ecosystems. It is time to stop—and ideally reverse—the population increase. To celebrate falling fertility is like congratulating the captain of the Titanic on heading towards the iceberg more slowly. The Malthusians are right that the world’s population is still increasing and can do a lot more environmental damage before it peaks at just over 9 billion in 2050. That will certainly be the case if poor, fast-growing countries follow the economic trajectories of those in the rich world. The poorest Africans and Asians produce 0.1 tons of CO2 each a year, compared with 20 tons for each American. Growth is helping hundreds of millions to escape grinding poverty. But if the poor copy the pattern of wealth creation that made Europe and America rich, they will eat up as many resources as the Americans do, with grim consequences for the planet. What’s more, the parts of the world where populations are growing fastest are also those most vulnerable to climate change, and a rising population will exacerbate the consequences of global warming—water shortages, mass migration, declining food yields.”

So who’s correct? Is the world headed for better or worse times? The Economist‘s answer is: “It depends.”

“In principle, there are three ways of limiting human environmental impacts: through population policy, technology and governance. The first of those does not offer much scope. Population growth is already slowing almost as fast as it naturally could. Easier access to family planning, especially in Africa, could probably lower its expected peak from around 9 billion to perhaps 8.5 billion. Only Chinese-style coercion would bring it down much below that; and forcing poor people to have fewer children than they want because the rich consume too many of the world’s resources would be immoral. If population policy can do little more to alleviate environmental damage, then the human race will have to rely on technology and governance to shift the world’s economy towards cleaner growth. Mankind needs to develop more and cheaper technologies that can enable people to enjoy the fruits of economic growth without destroying the planet’s natural capital. That’s not going to happen unless governments both use carbon pricing and other policies to encourage investment in those technologies and constrain the damage that economic development does to biodiversity. Falling fertility may be making poor people’s lives better, but it cannot save the Earth. That lies in our own hands.”

One hitch in predictions being made about population is that fertility rates in some developed countries have started to rise [“Population: In the family way,” Financial Times, 9 December 2009]. The article reports:

“If scientists still dispute the causes and effects of the declining fertility that generally accompanies economic development, they at least agreed on the trend – until recently. In August, a paper published in the scientific journal Nature by Mikko Myrskylä at the University of Pennsylvania identified an intriguing pattern: in some rich countries, there appeared to be an uptick in fertility. Using data from 1975, he and his colleagues confirmed a classic straight-line inverse correlation between wealth and fertility in dozens of countries. A fall in total fertility rates – the theoretical number of births in a woman’s reproductive lifetime – coincides with a rising score on the UN’s human development index, a measure of standard of living, education and life expectancy. But replotting to include data from 2005, they spotted a striking number of exceptions among richer countries that had exceeded the very high score of 0.9 on the index, suggesting instead a rotated ‘J’ curve – the start of a rise after a steady drop. The US, the UK, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Germany were among those showing a recent rise in fertility.”

The exact reasons for this uptick in births haven’t been identified. Nevertheless, the article notes, the study’s conclusions have “sparked a fierce debate.”

“Rival academics have questioned the reliability of the data, and also how far it is possible to compare different countries over time. There is equal disagreement over the implications of the findings. The good news is that more children per adult could help ease concerns over how to support ageing populations, and provide a fresh input of energy and ideas. But the catch is that additional children entering the workforce would not necessarily be happy to support their elders. In any case, they would also substantially raise energy consumption, accelerating climate change. An increasing number of births in richer countries could also harden attitudes towards immigrants coming in to work. Just as demographers are starting to debate the old maxims about the dampening effect of development on high fertility among the poor, so the accuracy of the long-established credo of low fertility among the rich is being called into question.”

In a companion article in The Economist, the difference between birthrate and fertility rate is explained [“Go forth and multiply a lot less,” 31 October 2009 print issue].

“The fertility rate is a hypothetical, almost conjectural number. It is not the same as the birth rate, which is the number of children born in a year as a share of the total population. Rather, it represents the number of children an average woman is likely to have during her childbearing years, conventionally taken to be 15-49. If there were no early deaths, the replacement rate would be 2.0 (actually, fractionally higher because fewer girls are born than boys). Two parents are replaced by two children. But a daughter may die before her childbearing years, so the figure has to allow for early mortality. Since child mortality is higher in poor countries, the replacement fertility rate is higher there, too. In rich countries it is about 2.1. In poor ones it can go over 3.0. The global average is 2.33. By about 2020, the global fertility rate will dip below the global replacement rate for the first time. … In the 1970s only 24 countries had fertility rates of 2.1 or less, all of them rich. Now there are over 70 such countries, and in every continent, including Africa. Between 1950 and 2000 the average fertility rate in developing countries fell by half from six to three—three fewer children in each family in just 50 years. Over the same period, Europe went from the peak of the baby boom to the depth of the baby bust and its fertility also fell by almost half, from 2.65 to 1.42—but that was a decline of only 1.23 children.”

As the above article highlights, fertility rates differ widely between geographical regions and sometimes between neighboring countries. This means that population challenges also differ widely. In some countries, efforts are still being mounted to help curb burgeoning population growth. Kenya is one of those countries [“In the family way“, Financial Times, 9 December 2009].

“Five years ago, Boniface K’Oyugi began to receive troubling news. After 30 years during which family planning programmes had halved the number of births per woman in Kenya to fewer than five, the trend went into reverse. … His concerns reflect a growing worry that some developing countries have failed to follow the broader ‘demographic transition’ to lower fertility levels that has occurred in past decades in the western world and more recently across Latin America and much of Asia. Experts and policy-makers are calling increasingly for a renewed and more nuanced approach to family planning, focused on countries in sub-Saharan Africa as well as others such as Yemen and Pakistan that trail the trend.”

Data like that coming out of Kenya has caused renewed concern among policymakers and environmentalists.

“With Africa’s population symbolically now reaching 1bn people, and the current debate on climate change provoking new concern about the effect of further births, there is a broader effort to shake off the complacency of recent years. ‘If you look at countries like Mali, where the population is doubling, agricultural production has not kept up and land is being lost to desertification, you are really in for a Malthusian disaster,’ says John Cleland from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The solutions, he argues, are cheap and well understood: the provision of contraceptives to the 200m women who are estimated to want them but are unable to gain access. They need enhanced family planning services, subsidies and promotional programs, with support from doctors, teachers and political leaders. ‘All the lessons were learnt 20 years ago,’ says Prof Cleland.”

Debates remain about whether development is a necessary precondition for falling fertility rates or whether lower fertility rates can help promote development.

“A long-standing view holds that poverty reduction comes before family planning; that the birth rate falls only once the costs of having more children exceed the benefits. Conception remains high as long as parents have children who die in large numbers, want extra hands to work their land or see few sources of support in retirement other than their own offspring. Yet this pattern – with family size falling simply as the consequence of development – is not universal. Active family planning in Nepal and Bangladesh in the late 20th century significantly reduced fertility rates in countries that were still poor, for example. ‘It is not so much a question of which comes first as of getting a virtuous circle of reinforcing changes going,’ says Stan Bernstein at the United Nations Population Fund, pointing to all the women who want but do not have contraception. ‘The challenge is not to make something happen that isn’t in progress but to see that the benefits and opportunities are available to all.’ Historically, childhood deaths and adult infections have fallen largely as a result of improved nutrition and sanitation spurred by economic growth. But in recent years, medical advances and increased funding rapidly extended vaccinations and treatments for many infectious diseases across the developing world. John May, a specialist in African demography at the World Bank, says: ‘Economic and social development is of course the best contraceptive, but contraceptives are also good for development.’ When fertility is high and population growth rapid, he adds, instead of a virtuous circle there emerges a vicious one. A recent study by his agency argued that demographic factors predicted two-thirds of the shortfall in sub-Saharan Africa’s economic growth compared with other developing regions. The burden of parents looking after their children and the instability of rapidly rising youth unemployment were the main constraints. Such views helped trigger funding for family planning programmes in the second half of the last century, providing contraceptives, counselling and abortions to supplement traditional methods led by abstinence and prolonged breast-feeding to stagger births further apart. They were supported by non-profit groups such as the International Planned Parenthood Federation and large donors led by the US, notably beginning with President Richard Nixon. They culminated in the UN international conference on population and development in Cairo in 1994, which called for comprehensive sexual and reproductive health provision. But funding and political commitment never matched the rhetoric.”

While African countries struggle to make the demographic transition to lower fertility and consequent economic development, countries like China are struggling with the opposite challenge — too low of a fertility rate [“Looming population crisis forces China to revisit one-child policy,” by Ariana Eunjung Cha, Washington Post, 12 December 2009]. Cha reports:

“More than 30 years after China’s one-child policy was introduced, creating two generations of notoriously chubby, spoiled only children affectionately nicknamed ‘little emperors,’ a population crisis is looming in the country. The average birthrate has plummeted to 1.8 children per couple as compared with six when the policy went into effect, according to the U.N. Population Division, while the number of residents 60 and older is predicted to explode from 16.7 percent of the population in 2020 to 31.1 percent by 2050. That is far above the global average of about 20 percent. The imbalance is worse in wealthy coastal cities with highly educated populations, such as Shanghai. Last year, people 60 and older accounted for almost 22 percent of Shanghai’s registered residents, while the birthrate was less than one child per couple.”

This demographic imbalance is likely to cause economic challenges for China in a near future. Even though the controversial one-child policy is credited with helping China achieve rapid economic growth, the policy now threatens the country’s economic future. Not only because the country is aging rapidly, but because “many couples have had sex-selective abortions, leading to an unnaturally high male-to-female ratio.” As a result, support for the controversial policy is waning.

“In 2004, they allowed for more exceptions to the rule — including urban residents, members of ethnic minorities and cases in which both husband and wife are only children — and in 2007, they toned down many of their hard-line slogans. Qiao Xiaochun, a professor at the Institute of Population Research at Peking University, said central government officials have recently been debating even more radical changes, such as allowing couples to have two children if one partner is an only child. In July, Shanghai became the first Chinese city to launch an aggressive campaign to encourage more births. Almost overnight, posters directing families to have only one child were replaced by copies of regulations detailing who would be eligible to have a second child and how to apply for a permit. The city government dispatched family planning officials and volunteers to meet with couples in their homes and slip leaflets under doors. It has also pledged to provide emotional and financial counseling to those electing to have more than one child.”

Interestingly, the results of the campaign to increase births have been disappointing. “Shanghai officials say that, despite the campaign, the number of births in the city in 2010 is still expected to be only about 165,000 — slightly higher than in 2009 but lower than in 2008.” Clearly, the global demographic story is not fully written. Twists, turns, and surprises in the population plot continue to keep analysts busy and policymakers concerned. The evidence, however, clearly indicates that lower fertility rates generally create a better economic environment and improve the quality of life for a nation’s populace. As noted at the beginning of this post, getting the population in some sort of equilibrium will help make planning for sustainable economies easier.